Lab Notes

Short stories and links shared by the scientists in our community

Carpet pythons are the second-biggest predator of wild koalas

New technology for koala tracking led to this discovery, uncovering a previously unknown ecological relationship between the two species

Photo by Adrian Pereira on Unsplash

Koalas may be one of Australia’s most charismatic animals, but there’s still a lot we don’t know about them. For example: what animals prey on them, and how often?

Between 2013 and 2017, 503 free-living koalas got fitted with telemetry collars, which allowed scientists to find them in the wild, record their positions, and importantly, detect when they were dead. Over these four years, scientists tracked koalas and recovered those that perished. Or at least they tried to — some were tracked to the inside of carpet pythons!

Experienced veterinarians examined the retrievable koala bodies and determined causes of death through a necropsy, which is an autopsy for animals. With these results, the realization that carpet pythons do prey on wild koalas, and knowledge about carpet python behavior, the study authors were able to accurately estimate how many koalas died from carpet python predation. And it was more than initially expected.

sipa on Pixabay from Needpix

Carpet pythons seem to kill more koalas than they can swallow. In most cases attributed to carpet python mortality (62%), koalas were killed by asphyxiation with evidence of attempted ingestion, but the koala carcass was ultimately abandoned.

This finding enabled scientists to pinpoint the signs of carpet python predation attempts: identification of a bite site, slicked fur from the snake's saliva, and damage to the lungs caused by the pythons wrapping their body around the koala’s body. We now know that carpet pythons are the second biggest predator of wild koalas, behind wild dogs (dingo relatives, not to be confused with the dogs we keep as pets). This is an important finding that will allow wildlife managers to identify safe koala habitat.

On National DNA Day, scientists are trying to take the colonialism out of genetics

Krystal Tsosie is working to decolonize genetic research and better include Indigenous communities

Scientists are trying to tackle the lack of diversity seen in genomics research, but even ambitious efforts, like the NIH’s All of Us program, often fall short, especially when it comes to the inclusion of Indigenous communities. This is one of the reasons why the Decolonize DNA Day conference is taking place on April 24th, one day before the National DNA Day.

Traditionally, National DNA Day is an annual celebration of the discovery of DNA's double helix structure (1953) and the completion of the Human Genome Project (2003).

“I was having conversations with colleagues on what would it mean to decolonize DNA,” says Krystal Tsosie, an Indigenous (Diné/Navajo) PhD student at Vanderbilt University. “As an Indigenous academic, we always talk about what it means to Indigenize and re-Indigenize different disciplines of academia that have been historically more white-centred or white-dominated... and what it would mean to remove the colonial lens.”

In collaboration with Latrice Landry and Jerome de Groot, Tsosie co-organized the Decolonize DNA Day Twitter conference to help re-frame narratives around DNA. Each speaker will have an hour to tweet out their "talk" and lead conversations on various topics, including how DNA ancestry testing fuels anti-Indigeneity and how to utilize emerging technologies to decolonize precision medicine.

“There is a divide between people who are doing the science or the academic work, and the people who we want to inform,” says Tsosie. “Twitter is a great way to bridge that divide.”

The Decolonize DNA Day conference is simply one effort to Indigenize genomics. Tsosie is also a co-founder of the Native BioData Consortium, a non-profit organization consisting of researchers and Indigenous members of tribal communities, focused on increasing the understanding of Native American genomic issues.

“We don’t really see a heavy amount of Indigenous engagement in genetic studies, which then means that as precision medicine advances as a whole […] those innovations are not going to be applied to Indigenous people,” says Tsosie. “How do we get more Indigenous people engaged?”

Some of the answers can be found in a recent Nature Reviews Genetics perspective, penned by Indigenous scientists and communities, including those from the Native BioData Consortium. The piece highlights the actions that genomics researchers can take to address issues of trust, accountability, and equity. Recommended actions include the need for early consultations, developing benefit-sharing agreements, and appropriately crediting community support in any academic publications.

“By switching power dynamics, we’re hoping to get genomic researchers to work with us, instead of against us,” says Tsosie.

Regular soap and water is enough to fend off coronavirus. Don't use antibacterials

Antibacterial soaps are no more effective than regular soaps, and could be doing harm down the line

Photo by Mélissa Jeanty on Unsplash

As an evolutionary biologist, I am more worried about our current cleaning habits than I am about COVID-19. Good, sanitary practices are a good thing, but what worries me is how we are dealing with mass sterilization to combat the virus.

COVID-19 is a virus. Hand washing is preferable to using hand sanitizer because it physically knocks viruses off your skin. It turns out that plain old soap is really effective against viruses. But many soaps add extra antimicrobial or antibiotic chemicals into their mixture, ostensibly boosting their efficacy. Here’s the problem: those antimicrobial additives only work on bacteria and fungi. They do nothing against viruses.

At least those antimicrobial soaps are killing off other germs, right? Yes, but that isn’t necessarily good. We harbor a huge variety of beneficial bacteria on and in our bodies and this microbiome is remarkably important to our health. More importantly, antibacterials are not 100% effective at killing all microbes.

Microbes can (and do) evolve immunity to antibiotics. In a war against disease-causing microbes, antibiotic agents are our best weapon. The more we apply antimicrobial agents, the more defenses microbes develop against them. The bacteria causing both staph infections (MRSA) and tuberculosis (TB) are already known to have multi-drug resistant strains, meaning they are immune to more than one class of antibiotic. These bacteria are evolving faster than we can develop new types of antimicrobials to fight them off. And as we throw antibiotics on surfaces to combat COVID-19, we could be aiding the development of something far scarier: antibiotic-resistant microbes.

So while we deal with the current pandemic, continue to wash your hands, but please be responsible and make sure your cleaning products and soap do not contain antibiotics or antimicrobial additives. Just stick to plain soap and water.

A real world version of Pokémon Go lets you track orangutans in the jungle

A new augmented reality smartphone game takes you into Borneo's jungles in search of great apes (and more!)

Internet of Elephants

Move over, Pokémon Go: the search is now on for real wild animals. A new augmented reality smartphone game, called Wildeverse, takes you deep into Bornean jungles in search of signs of orangutans and gibbons. And if you're lucky, you'll even meet the stars of the show on your screen.

The game — free to download in the Apple and Google Play stores — opens with you being assigned a mission from Amyra, the Wildeverse project leader. It's "Where in the World is Carmen San Diego?"-esque, which, as a 90's child, I thoroughly appreciated. Amyra sends you to a swamp forest in Borneo to try to track down wild orangutan Fio. The jungle trees, outlined as brilliant blue holograms spring up around you. Your first task is to find evidence of Fio on the ground (hint: 💩).

I haven't found the poop yet, but earlier this week I did chat with Gautam Shah, the founder of Internet of Elephants, the company behind the game. It was a strange twist of fate that Gautam, who I had previously spoken to about how games like his can advance wildlife conservation, partnered with an NGO I used to work with (Borneo Nature Foundation) to bring Fio and his gibbon counterpart Chilli to the smartphone screen. Buka and Aida, the game's other stars, live in the Congo, where Internet of Elephants partnered with the Goualougo Triangle Ape Project.

The game has already been downloaded 10,000 times, with minimal marketing outside of the UK. Gautam told me that the game had gotten good responses and that people like having a tropical jungle appear when they open their phones, "especially the first time they see Fio walk by." The game also has built-in questions to help track how people feel about wildlife, and how those feelings change as they play the game. As a conservation biologist I can tell you that data like that is highly valuable for figuring out what makes people want to protect nature and change their behaviors accordingly, which is one of Gautam's main goals for the game.

If you are looking for something new to entertain you during social distancing, why not celebrate Earth Day in the Wildeverse? I think I'll join you!

Fruit fly glue is sticky, no matter how you slice it

Adhesives found in nature could have applications for us

Many different organisms produce adhesives, including barnacles, sea cucumbers, and even some plants. Scientists are interested in these types of glue, as they often inspire applications in humans. In a recently published paper, researchers focused on the glue made by fruit flies. They were interested in testing exactly how adhesive the glue made by these insects was on different surfaces.

Fruit flies, just like butterflies, undergo metamorphosis. They start their life as larvae and go through several molting stages. Eventually they pupate and emerge as adult fruit flies. And just like butterflies, when it’s time for their metamorphosis, they glue their pupae to a surface, so they don't just roll or blow away.

Photo by Suzanne D. Williams on Unsplash

In this study, researchers took larvae in their final molting stage, just before they would pupate, and put them on a variety of surfaces. They then waited for the larvae to stick their pupae to the surface. When they did, the scientists attached the pupae to pieces of double-sided tape and measured the force they needed to apply in order to pull each pupa away from the surface.

Out of the 11 different types of surfaces the researchers tested, which included different types of glass and resins of various smoothnesses, the pupa could only be easily pulled away from teflon. In all other cases, the researchers needed a similar amount of force, regardless of whether the surface was hydrophobic (water-repellent) or hydrophilic (water-attracted). This led them to conclude that the glue from fruit flies is universally sticky.

Can hormone levels signal for autism in girls?

New study moves against the current of gender bias in autism research

Since the 1940's, when the word "autism" was introduced in the US, diagnoses and treatments have skyrocketed in prevalence and normalcy. In fact, the United States now estimates 1 in 54 American children have some form of Autism or Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). Despite the surge, the differences between people diagnosed makes pinpointing a specific cause nearly impossible.

However, one thing all experts agree on is the fact that autism seems to occur more often in boys than in girls. While many girls with autism may be overlooked due to sex or gender biases, studies have found the prevalence in boys to be four times higher.

Studies have looked at sex hormones, male-specific genes, and male vs. female brains to resolve this difference. And some have turned up answers. However, this disparity in research favoring boys neglects the girls with autism, whose struggles and needs are no less important, regardless of the fact that they are fewer in numbers.

A recent study from the University of Bern decided to instead tackle the question of cause with these girls in mind. The study analyzed certain hormones, particularly androgens such as testosterone, and their levels in teenage girls with autism.

They found that these girls had higher levels of both testosterone and androstenediol. But, they also found that those levels weren’t elevated in their urine. Plus, they had the same or lower levels of enzymes used to process those hormones.

This seems to implicate the brain’s hormone control center – the hypothalamus – in the cause. Their bodies seemed to be unaware of their elevated androgen levels, since they aren’t getting rid of them in urine or processing them with extra enzymes.

Finally, this study also suggests that changes in the levels of androgen hormones may be used as a diagnostic marker for autism. Such a diagnostic tool is an important step forward, as autism diagnosis currently based on behavior, movements, and development in early years, all of which differ significantly between children with and without autism.

Your socially isolated brain craves interaction with other people just as much as it craves a meal when you are hungry

New research highlights the neuroscience of why social distancing is so hard

Photo by Priscilla Du Preez on Unsplash

Social distancing has emerged as one of the most effective weapons against the spread of COVID-19. Yet social distancing, like any medicine, has side-effects: we’re probably all feeling a little lonelier and more isolated. New research [note: this is a pre-print and has not yet been peer-reviewed] by scientists at MIT and the Salk Institute for Biological Studies sheds light on the effects of mandatory social isolation on brain function.

Humans are a social species, and social interaction is inherently rewarding for us. The parts of our brains that are responsible for motivating us to go out and obtain rewards react to social interaction just like they do to receiving food or money. Interestingly, these parts of our brains react in anticipation of a future reward, and the magnitude of that reaction reflects how much reward we’re expecting. Scientists have found that the strength of your brain's reaction to a reward reflections how much you crave it. But is this also true for social rewards?

The scientists behind this new research spent over three years working to answer this question in humans. They recruited 40 participants into their study, and each participant was subject to three trials: one control condition, one in which they fasted for 10 hours, and one in which they sat alone in a room with no one to talk to (and no internet or social media) for 10 hours. Participants then had their brains scanned while they completed a task where they were shown images of food and social scenes – the very things they might be craving. This allowed the researchers to compare the effects of severe hunger with the effects of social isolation.

They found that, just as the brain over-reacted to pictures of food when the participants were hungry, it also over-reacted to pictures of social scenes when they were isolated. The hungrier or lonelier the participant felt, the larger the reaction. The size of the effect of fasting and isolation were also very similar, suggesting that when they were isolated, the participants craved social interaction just as much as they craved food when they were fasting.

This work helps to cement social interaction as an important and primary reward that all people need. Our brains are craving social interaction when we’re isolated, just like they would crave food if we were extremely hungry. What we don’t know, and one important direction for future research, is how much social interaction is sufficient, and how much of this craving social media is able to satisfy.

First patient receives CRISPR treatment for genetic eye disorder

The CRISPR gene therapy for Leber's Congenital Amaurosis is injected directly into the body

Photo by Amanda Dalbjörn on Unsplash

Remember the viral 2013 YouTube video featuring Gavin, a four-year old blind child walking independently with a white cane, and the hope that it stood for? Seven years later, there is another beacon of hope for kids like Gavin with Leber’s Congenital Amaurosis (LCA), a genetic eye disorder.

Recently, a patient with LCA at the Casey Eye Institute at Oregon Health and Science University in Portland made history as the first human to receive a new type of CRISPR gene therapy injected directly into their eye. The patient is one of the 18 people enrolled in a milestone clinical trial called BRILLIANCE, which is a collaboration between two giants, Allergan and Editas Medicine. Cynthia Collins, President and CEO of Editas Medicine said in a press release, “This dosing is a truly historic event – for science, medicine, and most importantly for the people living with this eye disease.”

LCA is a group of genetic, degenerative eye disorders caused by mutations in at least 18 different genes. It is the most common cause of inherited childhood blindness, with an occurrence of 2-3 per 100,000 births worldwide. The disease manifests itself in early years with severely affected eye cells and may quickly lead to blindness.

Though exciting, this isn’t the first attempt to cure inherited blindness using gene therapy. In December 2017, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the first directly administered standard gene therapy drug, Luxturna. However, this drug targets a different type of eye disorder and works differently than the CRISPR therapy for LCA.

Though research studies using genome-editing tools as a medicine have been undertaken for a decade, injecting CRISPR–Cas9 directly into the body marks a new dawn. Similar therapies, in the future, will increasingly employ CRISPR since it can be highly specified to cut DNA at certain therapeutic locations. The BRILLIANCE trial stands as a symbol of hope for patients with rare genetic diseases with no current cure available.

Simple science communication helps ease fears and spread good information during the COVID-19 pandemic

Epidemiologists Eleanor Murray and Benjamin Linas have created a set of posters for Boston-area patients, which have since been translated into many languages

Photo by Volodymyr Hryshchenko on Unsplash

People are bombarded with COVID-19 information and data every direction we turn on a daily basis, and often this can be daunting and overwhelming. Dr. Benjamin Linas of the Boston University School of Medicine and Dr. Eleanor Murray of the Boston University School of Public Health recognized this. Using stick figures, doodles and large font with clear instructions that benefit individuals with low literacy and limited English proficiency, Dr. Murray designed a fun and visually appealing poster of COVID-19 tips to help #flattenthecurve.

After sharing this first poster online and with Boston Medical Center patients, the social media community came together not only to help translate the poster into many languages, but to copy and proof-read, as well as distribute the poster widely to different communities.

The value and success of the poster was soon realized, and now is one of a series of posters with information and simple instructions about what people should do if they have been exposed to COVID-19, what to do while waiting for their test results, and what to do if their test is positive. Recently, a poster about what a person should do if they are hospitalized was addition to the collection highlighting how a lack of communication in a hospital setting further adds to a heightened state of stress.

All of these posters can be accessed and shared online. By following the simple instructions described in each poster, or helping to translate or share the posters with your family, friends, and on social media we can all help disseminate the information and play our part to #flattenthecurve.

Vegan gut bacteria swim more than their carnivorous counterparts

Gut bacteria from those on plant-based diets may be better at swimming to nutrients

The first decade or so of gut microbiome research was largely defined by "community composition profiling," essentially asking the question, "What types of bacteria are present in this sample?" More recently, there has been a really exciting shift in the field from asking who is there to asking what they are doing.

A recent study explored how diet affect the activity of gut microbes. To do this, the researchers analyzed stool samples from 61 volunteers who had been following either a vegetarian, vegan, or omnivorous diet for at least one year. The researchers tracked the bacterial genes and proteins found in each sample. Tracking certain genes and proteins was important. Scanning the genes asked, "What are these microbes able to do?" Scanning the proteins asked, "What are they actually doing in this moment?"

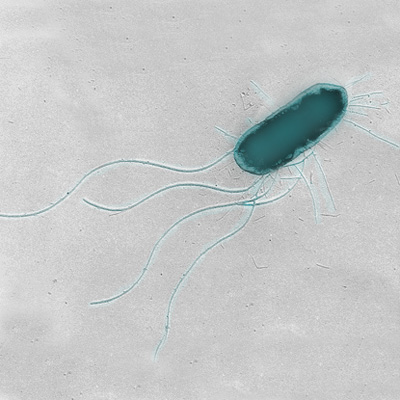

E. coli with tail-like flagella

Those on vegetarian and vegan diets tended to have the most genes and proteins related to cell motility — the cell’s capacity to move around. More broadly, the researchers found that dietary fiber intake was correlated with the amount of flagellin, a type of protein used to make the tail-like flagella, an essential bacterial appendage for swimming. The authors speculate that this increased cell motility is a mechanism for bacteria to more easily move around in order to access nutrients.

Vegetarian and vegan microbiomes also had more genes and proteins related to breaking down carbs and protein, and building up vitamins and amino acids. It makes sense that people eating a greater diversity of plants would have a greater diversity of microbial genes for breaking down different carbohydrate sources.

And that’s not totally surprising. A 2014 study found changes in microbiomes of participants who ate plant-based or animal-based diets for only five days. Still, the present study adds to our understanding of the precise types of changes that can occur from being on a specific diet-long term.

Hungry microbes turn crusty leftovers into wine

Old bread gets second life as microbe soup

Robert Cheaib from Pixabay

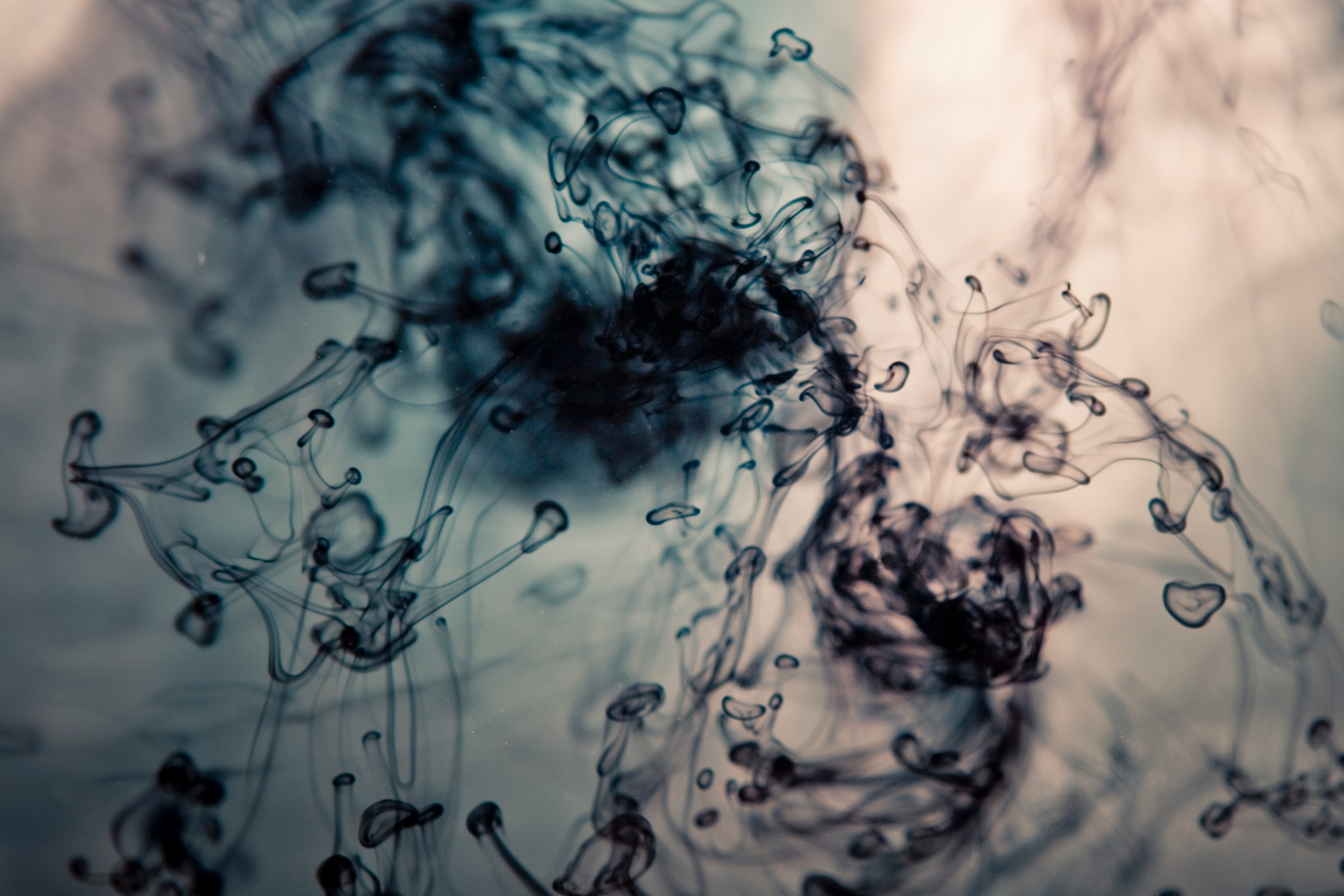

Globally, we produce about 100 million tons of bread every year. But because bread gets stale or moldy fairly quickly, a substantial amount of this bread is wasted. Now, scientists have come up with a use for all this bread that would otherwise be wasted: use it to grow beneficial microbes.

"r u gonna eat that?" - Hungry Microbe

Shutterbug75 from Pixabay

The food industry depends on many types of beneficial microbes; they’re used in the production of things like bread, beer, wine, cheese, and yogurt. In this study, researchers created a special growing medium that contained 50% “waste bread” (called wasted bread medium). Using this nutrient-rich soup, they were able to grow several types of microbes involved in the production of wine and yogurt. Importantly, they estimated that, at least on a small scale, the wasted bread medium only cost about 30% as much as traditional formulas used to grow these microbes.

If this process can be scaled up, it means that stale bread — which would ordinarily be thrown away — could live a second life as food for microbes that churn out fermented foods (and drinks!) like wine and yogurt. This would help decrease food waste and perhaps even drop the cost of growing these beneficial microbes.

Intergalactic pasta may hold the secrets to the universe

Like...why the universe exists

Massive Science

Science is facing a crisis. On the one hand, physicists claim to understand the stuff making up all that's visible in the sky. On the other, astronomers weighing the universe tell us that a staggering 85% of its heft lurks in something dark and unseeable. And nobody knows what this stuff — "dark matter" — is made of.

Learning the identity of dark matter would be revolutionary, and may supply the key to fundamental mysteries about our universe, such as why it exists. So here's a question to narrow our quest: does it touch us, or pass through us? Many physicists argue the former — and if something can touch us, we can trap and study it.

My collaborators and I think that the perfect trap for dark matter is... pasta. That's the name of giant atomic nuclei shaped like gnocchi, spaghetti, lasagna and bucatini in the bottom-most, densest layer of a neutron star's kilometer-thick crust.

Photo by Heather Gill on Unsplash

Neutron stars are the idle relics left behind by once-active stars that had ended their life in a supernova. They span 20 km in size, and are the densest known objects in the universe: a teaspoon of their stuff weighs the same as Lake Michigan. And their material is packed in several onion-like layers.

We think that dark matter particles would batter ancient, (literally) ice-cold neutron stars and heat them up to (literally) barbecue temperatures, making them visible at next-generation infrared telescopes such as James Webb, the Thirty Meter Telescope, and the Extremely Large Telescope. And we find that pasta is the most likely layer getting battered.

Pasta-aided detection of dark matter would be a triumph of the fields of particle physics, nuclear astrophysics, and astronomy. It looks increasingly like the answers to fundamental puzzles plaguing science would come from such cross-disciplinary interactions.

NASA celebrates 50 years since Apollo 13, their most successful failure

New video visualizes the Moon's surface as the Apollo 13 crew witnessed it

NASA

April 11th marks the 50th anniversary of NASA’s “successful failure,” Apollo 13. This mission was the 13th of 17 US lunar missions planned in a span of 4 years and change. The 17th, in 1972, was the last time a human stomped around on the Moon.

Unlike the successful Apollo 11 — one small step, one giant leap, etc. — Apollo 13 is considered a failure. The mission intended to plop some Americans back on the moon for the 3rd time. The mission was on shaky footing even before they were off the ground. One astronaut inadvertently infected another with rubella. Rather than delay the launch, NASA tagged in a backup astronaut who trained with the crew.

A NASA mug from my childhood in Florida. For some reason, they didn't have any for my sister, Noemie.

Max Levy

Two days after liftoff (and 200,000 miles away from the nearest rocket shop) one of their oxygen tanks exploded. To bring the crew back safely, NASA devised a way to swing the crew’s lunar module around the moon and back to Earth. The saga’s radio feed inspired the legendary “Houston, we have a problem,” misquoted by Kevin Bacon in that movie with Chet Hanks’ dad.

To commemorate this occasion, NASA released one of the most remarkable videos I’ve ever seen: a 4K visualization of what the Apollo 13 crew saw as their ship swung around the Moon. The video, produced by NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland, is based on real data captured by Apollo 13.

Here are some other historic images to celebrating the mission:

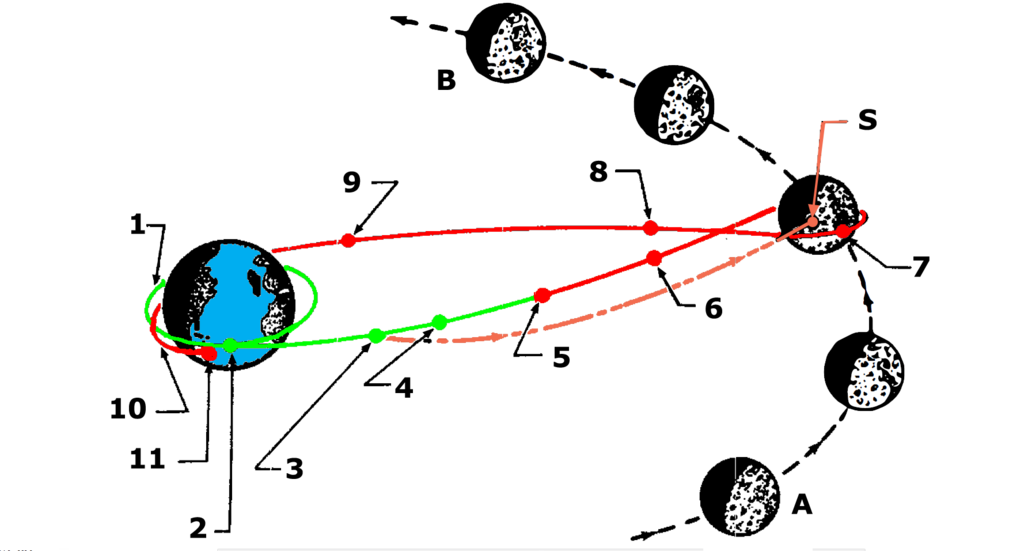

4 aborted missions

Apollo 13 Lunar service module

Wikimedia

Moon, as seen by the Apollo 13 crew

Apollo 13 voyage

Wikimedia

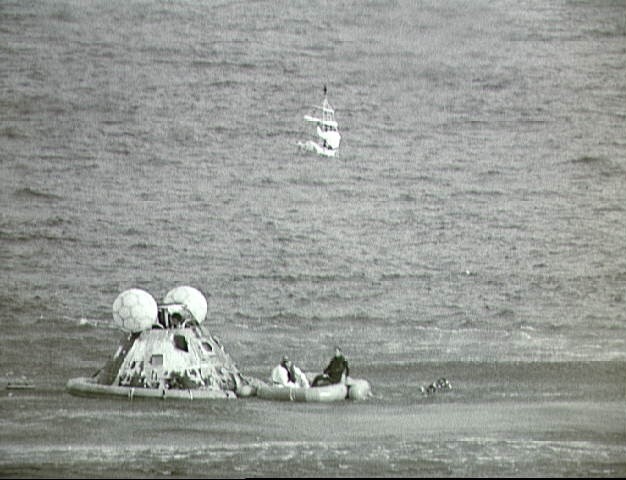

Apollo 13 crew returns safely and awaits rescue

.jpg)

"Hey do you mind parachuting down again? I got my thumb in the pic"

Wikimedia

LEGO bricks can take hundreds of years to degrade

Just because they're not single-use doesn't mean that they're great for the environment

Alan Chia / CC BY-SA

More people are avoiding single-use plastics. One of the main concerns is that once thrown away, plastic remains on the planet in landfills for hundreds of years — taking up space and creating pollution. It’s fairly easy to avoid things like plastic bags, but what about larger plastics that we consider “reusable”? One recent article in the journal Environmental Pollution uses common LEGO bricks to illustrate the concerning environmental effect of larger “reusable” plastic products.

Researchers at the University of Plymouth in the UK used LEGO bricks that had been collected by beach cleanup volunteers in Cornwall, England.

Photo by Rick Mason on Unsplash

They wanted to use these bricks to determine durable plastic persistence in the oceans. They could easily distinguish LEGO bricks by their shape and precisely date them by using X-ray fluorescence to determine their composition. In this case, the recovered bricks contained brightly colored yellow and red cadmium-based pigments. This chemical fingerprint told them that the bricks had to be manufactured in the late 1970s, during the short time frame in which manufacturers included these highly toxic pigments in toys.

To establish their comparison, the researchers matched the recovered bricks with bricks of similar chemical compositions in collections of unopened bricks from the same time period. The mass loss between the weathered and unweathered bricks suggested that LEGO bricks should persist in a marine environment for 100-1300 years.

Photo by Jonathan Chng on Unsplash

Compared to LEGO bricks, single-use plastics like disposable water bottles degrade in a relatively short amount of time, tens to hundreds of years. However, as the world moves away from single use plastics, we are becoming increasingly dependent on thick and durable plastics to make components for things like electronics. And we are also becoming increasingly more likely to throw these things away, creating not just more pollution, but longer lasting pollution. Current materials research on developing material that is durable yet also degradable is a huge step to reducing pollution, while still providing us with products we need in a modern world.

Finally, proof that honeybees are bullies

New research finds that honeybees might push smaller bees off the nectar motherlode

Honeybees may be in decline globally, but in a field of flowers they still reign supreme over smaller, wild, native bee species. Due to our agricultural system’s reliance on transporting honeybee hives from other states to pollinate crops, honeybees often dominate the nectar and pollen scene in agricultural fields. But to date, researchers have had a hard time quantifying competition between honeybees and wild species because it is hard to pinpoint whether honeybees actually deprive native bees of any foraging opportunities.

A new study published in the journal Acta Oecologia looked at whether wild, native bees were relegated to different times of the day or parts of a flower in the presence of honeybees. The researchers, from two collaborating laboratories in France, collected bees they found visiting cornflowers throughout July and August, when the plant is in bloom.

Cornflowers are special because they have what are called extrafloral nectaries – meaning that parts of the plant other than the flower carry nectar. In the case of the cornflower, these plants excrete small droplets of nectar just below the flowerhead. For bees, it’s a nice extrafloral snack. But the droplets don’t offer as much nectar as the flower itself and this snack spot doesn’t have any pollen – which bees need to feed to their growing larvae.

.jpg)

A bully devouring someone else's lunch

Wikimedia

Sure enough, the scientists found that 82.5% of the cornflowers visitors were honeybees, regardless of the time of day. But the breakdown of visitors at different locations on the flower revealed something interesting. Most of the smaller bees that did brave the cornflower foraging scene were found lapping up nectar from those extrafloral nectaries below the flowerhead.

Therefore, while both types of bees were technically found visiting cornflowers, paying attention to where on the flower these visits took place suggests that, compared to smaller bees, honeybees are monopolizing access to the nectar motherlode and the pollen stash.

Cleaner fish learn how to steal a little mucus snack by watching adults

Fish preferred to cheat a bit when given the choice

prilfish on Flickr

How do we learn when to cooperate, and when to cheat? It likely depends in part on the social interactions we observe growing up. Turns out that the same is true for cleaner fish (Labroides dimidiatus), according to a recent study.

Cleaner fish, also known as bluestreak cleaner wrasse, feed on ectoparasites found on other fishes — their “clients.” What cleaner fish really like to eat, however, is the protective mucus that covers their clients’ bodies. While eating ectoparasites is great for client fishes, cheating by eating mucus is bad. Client fishes will punish cheaters by fleeing, or by chasing the cheaters around.

Photo by David Clode on Unsplash

What’s the best option, to cheat and eat a brief but delicious snack (and risk being chased around), or to cooperate and eat a larger, peaceful, but not as tasty meal? A group of researchers led by Noa Truskanov, from the University of Neuchâtel, set out to understand how juvenile cleaner fish learn to answer that question.

In a series of experiments recently published in Nature Communications, Truskanov and her collaborators allowed juvenile cleaner fish to observe adults interacting with model clients. They then placed these juveniles in the same situations they had just observed, and tested if they copied the adult fish, learned from the adult fish, or behaved independently of what they had just seen.

Their results show that juvenile fish are actively learning to cooperate by observing the interactions of adult fish with their clients. Juvenile fish are more cooperative when client fishes are intolerant of cheating. When given the choice, however, they prefer clients who allow them to cheat a little. Juvenile fish also didn’t just imitate random adult preferences, showing that there are not copying, but rather learning.

Although both social learning and cooperation are widespread in nature, examples of animals that learn socially how to cooperate are extremely scarce. This leads us, humans, to erroneously assume that we are the only ones who learn to cooperate by observing others. Cleaner fish are putting us right back in our place: they can do it, too.

Squid bamboozle predators with elaborate ink-based dancing and weaving

They also deploy multiple moves and tactics to avoid being eaten

When a Japanese pygmy squid gets attacked, it will use its ink as a decoy so that the predator attacks the ink instead. It's not just a visual decoy — ink will also throw the predator of the squid's scent, literally. However, distracting a predator is not as easy as just releasing a single cloud of ink. In a recent video article, researchers showed that the Japanese pygmy squid use elaborate methods to mislead their predators.

Photo by Vincent Botta on Unsplash

When the squid are followed by a predator or, in this case, a scuba diver pretending to be a predator, they will often first change their color to be pale, which is less obvious in the water. They then swim away in a straight line, releasing little puffs of ink behind them. After releasing a few puffs, they will do one of two things: either they suddenly stop, or they suddenly change direction.

If they suddenly stop in what's called an S-stop, they will often also darken their color, so that they seem like one of the ink clouds, and the predator is unable to find them. If they change direction, called a C-change, they will remain pale, thus being as inconspicuous as possible. In both cases, the goal is for the predator to be distracted by the ink clouds and attack the decoys instead. The researchers showed that if the squid released more ink clouds during their escape, predators were more likely to attack those instead of the squid.

The question remains whether all squid have similar behaviors, or whether each species has evolved its own behavior to avoid predation. This might have to do with the specific species predating on the squid and their surroundings. In any case, judging from the study’s videos, it looks like its methods work pretty well for the Japanese Pygmy squid.

No more coronavirus takes

Please I'm begging you

Photo by Sebastian Herrmann on Unsplash

There is only one story now and I know it by heart. Everybody is telling one variation on it or another. Some of them are the political takes:

Some of them are economic, cultural, economic again, and political again, like at the New York Times:

Literally as many stories as I could fit into a screenshot

(this isn't even to mention the genre of celebrities announcing their diagnoses like the birth of a royal child:)

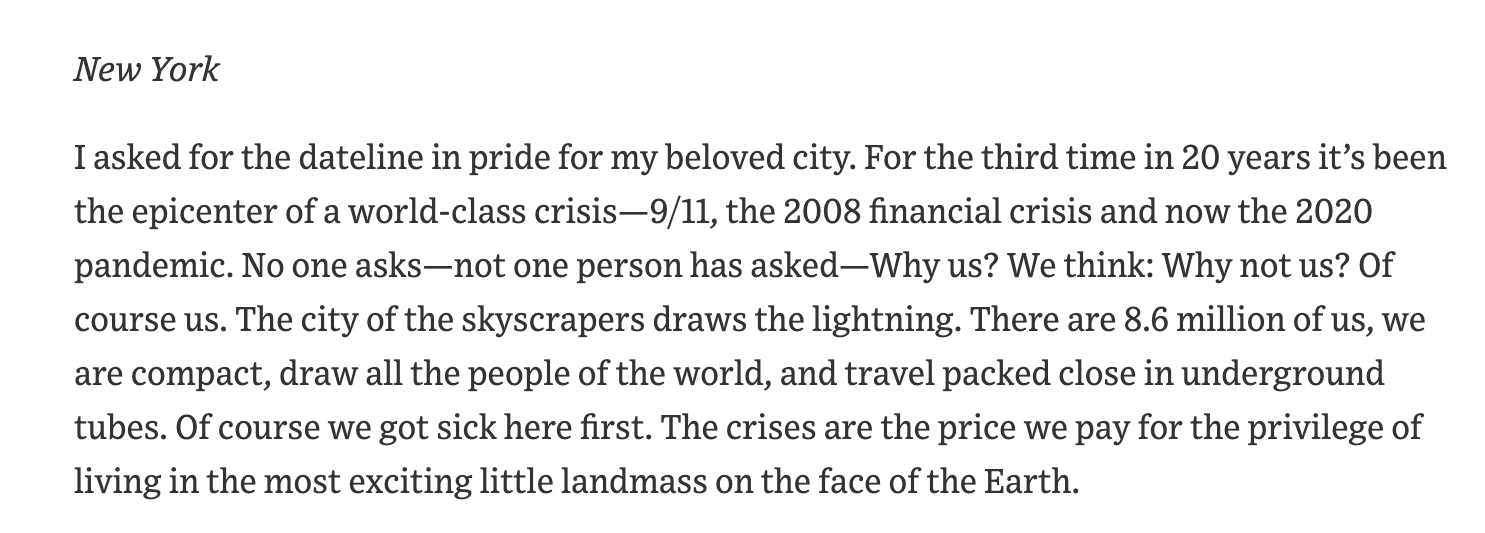

At the absolute bottom of the pile, way down in the dirt, is Peggy Noonan's paean to the quintessentially New York experience of death and ruin:

NEW YORK *cough cough* NEW YORK

Baby no one does a crisis like New York.

Many of these are from writers and publications I like and admire (not Peggy Noonan). But still! I'm begging! You! No more! Have mercy on me! No more coronavirus takes!

It's a gold rush out there for coronavirus stories, since it's basically all anyone wants to read right now. And yes, writing this is like sending a cease-and-desist letter to a tornado. But please let me vent this gas.

No more takes. Got coronavirus news? Great, I want to read it. Got coronavirus science? Even better. Got a coronavirus take? Unless you're an epidemiologist or you work on the frontline, I don't care. You don't know anything. No one does.

I encourage you all to write those stories you've been sitting on for ages. Now's the time. Hell pitch me your story. But if I read the word "coronavirus" one more time I might literally explode, right here in my kitchen, in my pajamas, the way I've always wanted to die.

Scientists name new species after its belly full of plastic

Plastic pollution reaches new depths – and new guts

Johanna Weston, Alan Jameson - Newcastle University, WWF Germany, via Wikipedia

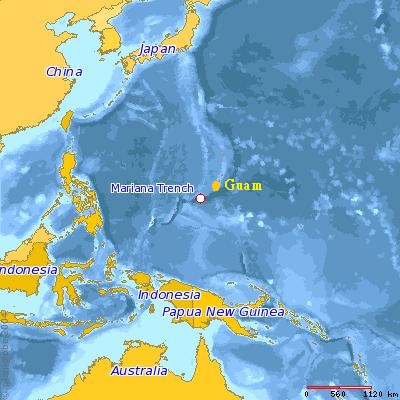

The deepest location on Earth sits below 6.8 miles of the western Pacific Ocean, deep enough to hold Mount Everest and prevent it from reaching the ocean’s surface. It is part of a 2,550 km (1580 miles) long trench, known as the Mariana Trench. At those depths it may seem a sanctuary from our plastic pollution. Unfortunately, that is wrong.

In November 2014, a group of scientists discovered a new species of crustacean within the Mariana Trench (pictured above). Crustaceans are a large class of organisms with an exoskeleton that includes lobsters, shrimp, crabs, and krill. Upon examining the organism’s body, scientists found a microplastic fiber in its gut. They named it Eurythenes plasticus to draw attention to the current plastic pollution crisis.

Microplastics are small pieces of plastic pollution in the environment that are less than the width of a pencil. Scientists have found them in every corner of the globe – even in the atmosphere and in arctic ice. Organisms like E. plasticus that feed on scraps are highly susceptible to ingesting microplastics from dead organisms and sediment. We’re not immune either. Alarmingly, microplastics can even work their way up the food chain and eventually reach us.

Mariana Trench, the deepest point on Earth

Wikimedia

This study adds to a growing body of research finding wildlife to be ingesting microplastics, including birds, whales, fish, and sharks. It is tragic that organisms in such remote places can be affected by humans before we have the chance to encounter them. Hopefully all these cases remind us to be more conscientious when considering the use of non-reusable plastics.

Scientists use the humble slime mold to map the universe's cosmic web

This mysterious Earth-dwelling organism can tell us a lot about the structure of outer space

Frankenstoen on Wikimedia Commons

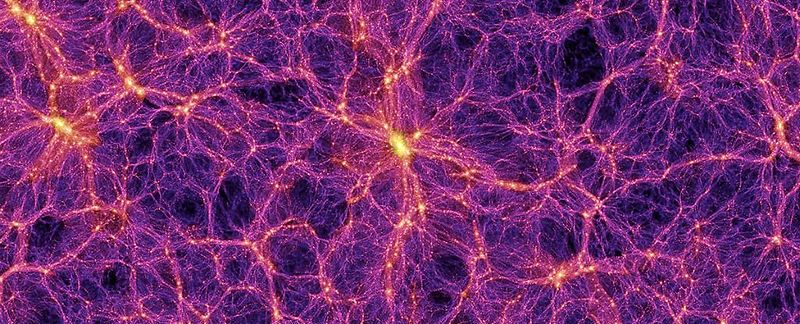

What do a single-celled slime mold and outer space have in common? Enough, it turns out, that researchers were able to use the behavior of the slime mold Physarum polycephalum to develop an algorithm to map the previously elusive cosmic web structure of the universe.

It started when scientists at the University of California at Santa Cruz were searching for a way to visualize the cosmic web. Composed of dark matter and laced together with thin gas, the cosmic web provides structure to the universe. Oskar Elek, a computational media scientist on the team was inspired by the work of Sage Jenson, a Berlin-based media artist who creates art by using algorithms to mimic biological properties, such as the growth of slime mold.

The slime mold, Physarum polycephalum, uses a complex web of filaments to find food. The scientists couldn’t help but notice similarities between the mold’s food-seeking web and the theorized cosmic web that connects the galaxies. Published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, the group developed a three-dimensional computer model of the buildup of slime mold to estimate the locations of many of the cosmic web’s filaments.

By using data previously acquired by the Sloan Digital Sky Survey and the Hubble Spectroscopic Legacy Archive, the researchers created a new view of the galaxy.

First, they applied the “slime mold algorithm” to data containing the locations of 37,000 galaxies at distances as far as 300 million light-years and came away with a three-dimensial map of the underlying cosmic web structure. They also used data from quasars, massive objects billions of light-years away that emit huge amounts of light energy, to visualize the extremely thin hydrogen gas signatures on the web that had been previously undetected. With the large scale structure in hand, the group hopes that they can now map specific trajectories that galaxies take as they move through the universe.

Remember this story the next time your microbiologist friend says they don’t have anything in common with your particle physics friend. The most impressive advances in science are often those made by scientists who work together and build connections between fields.

How do predators learn to avoid the colors and patterns of poisonous prey?

Using video games, scientists show it has to do with the environment and network of prey available

We have all heard about the extraordinary animals that use chemical defenses to avoid predation, and how their usually bright colorations warns predators about their unpleasant flavors (a skill called aposematism). But, how do predators learn to avoid eating prey with these defenses?

Previous studies suggest that how quickly a predator learns about color patterns depends on the complexity of the prey community – that is, the number of different patterns and the abundance of toxic prey. But testing this hypothesis using natural populations can be incredibly challenging.

A group of researchers came up with a clever solution: they used a videogame played by humans! In this videogame (you can play it here), they tested two different prey communities based on real aposematic butterflies from the tropics. One was a simple community with four color patterns and a high probability (50%) of encountering toxic butterflies, affecting the player’s score; the other, a complex community with ten color patterns and a reduced probability (20%) of finding a toxic butterfly.

The data collected shows that predators – humans in this case – are much better learners when only four color patterns were present. But this doesn’t mean that we can’t learn to avoid toxic patterns in a complex community: humans learned better when the toxic patterns were more similar to each other, and more different from the non-toxic patterns.

This fun experiment confirmed that the protection given by aposematism increases when the community has fewer color patterns, more toxic animals, or when the color patterns are more different between toxic and non-toxic animals. The authors think that these results are representative of what other predators, such as birds and other mammals, may experience in nature.

Experiments like this one help scientists closely examine animal behaviors that depend on multiple factors that are difficult to manipulate in natural settings. But at the same time it gives us perspective, reminding us of how much human behaviors were shaped by our evolution before civilization happened.

Stuck at home? College chemistry lessons are on TikTok, with Katy Perry accompaniment

One professor hopes that having General Chemistry students make their own TikToks teaches a broad audience about science

By Afif Kusuma on Unsplash

Timothy Su, an Assistant Professor of Chemistry at the University of California, Riverside, had been enjoying watching science videos on TikTok, a relatively new social media platform that is popular among Gen Z. That is when he got the idea to incorporate the new teen obsession into his classroom. He told his General Chemistry class, sized about 300 students, that he would give them extra credit if they created videos explaining general chemistry concepts using TikTok. About 65% of his students participated, far beyond Su’s expectation.

Su said that UC Riverside students come from various backgrounds. “I was hoping that the enthusiasm for science would go viral [in students’ communities],” Su said to me in an interview. Even though he was not expecting the videos themselves to go viral, to his and students’ surprise, some of the videos did very well in terms of popularity; as of this writing, the most liked video made by his students gained upwards of 49,000 likes on the platform.

Su is hoping to expand this practice to the other courses he will teach. “18-year-olds are brilliant in ways that I'm not,” Su said. “How people engage with learning is changing rapidly, so it’s good to be open-minded and communicate with students in their terms.”

Below are three of the most popular videos that Su’s students made. You can find more of these videos here.

Protecting forest cover could reduce flood risks

A study highlights the importance of forests to mitigate the effects of natural hazards on mountain infrastructure

In many mountainous regions, such as the European Alps and the Rocky Mountains, natural hazards threaten infrastructure such as roads, buildings, and railways. These natural hazards have globally increased by almost 70% in the last 30 years because of climate change. Triggered by harsh rainfall and storms, these hazardous events include rockfalls, landslides, floods, and debris flows, or a large mass of loose material moving down a slope.

However, it is well established that forests protect mountainous regions from natural hazards. Tree roots can decrease the availability of loose material by stabilizing the soil in steep terrain. In addition, forest canopies catch and collect rainfall, reducing surface water runoff. Getting rid of that forest canopy, either by human timber harvesting or natural causes like bark beetles, also reduces the protective function of forests.

Recently, Austrian researchers performed a large-scale study based on a large Landsat satellite image database, documenting 3768 torrential hazards that occurred in the Eastern Alps during a period of 31 years. They confirmed that an increase in forest cover decreased the probability of torrential hazards, like floods. It also turns out that regularly reducing forest canopy, such as small-scale logging interventions to regenerate forests, is actually more detrimental for natural hazards than singular, occasional disturbance events.

Unmanaged forests – where human intervention is absent or minimized – may better help protect human infrastructure against natural hazards than managed forests. And that could be important to know in a future where we want mountain regions to become more resilient to increasing heavy rainfall events and canopy reduction predicted under climate change.

Oil spills melt the superpowers of the double-crested cormorant

Birds have to work harder to stay warm after being repeatedly exposed to spilled oil, study finds

Bird feathers are a superpower. Small, downy feathers keep birds, and sometimes you, warm during winter. Contour feathers help birds blend in with their surroundings. And interlocking, aerodynamic pennaceous feathers are what allow birds to soar atop air currents and stay dry when diving for fish. But if feathers have a Kryptonite, it turns out to be oil. Oil breaks feathers’ waterproof layer and can leave birds suddenly out in the cold.

This is the mechanism behind new research on the effects of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, which in April 2010 leaked 200 million gallons of crude oil into the Gulf of Mexico after a drilling rig exploded offshore. With the ten-year anniversary of this disaster just around the corner, findings about its various and immense impacts on wildlife are still trickling in.

Double doubled-crested cormorant

Wikimedia

The scientists, from several different wildlife research centers and universities, used a “Niche Mapper” model to estimate how much harder the double-crested cormorant, a fish-eating species, would have to work throughout its range to maintain its body temperature after being “oiled” to varying degrees. In the model, birds were either unoiled, or covered in oil once, three times, or six times. Using existing calculations of this species’ energetic expenditure at different times of day and ambient temperatures, the researchers showed that the most heavily oiled birds had to spend, on average, an additional 1.5 hours foraging each day just to make up for lost heat.

In addition to exhausting birds with an extra 1.5-hour foraging shift each day, the model suggests that repeat exposure to oil may threaten cormorants’ success at mating and breeding, or to store enough fat before migrating between winter and summer ranges. These are just a few examples of sublethal effects animals endure from oil exposure, many of which have yet to be evaluated for the dozens of species affected by the Deepwater Horizon spill.

Just how hot was this winter?

Really hot. And that doesn't bode well for the rest of the year.

In the United States, this January and February were some of the hottest months on record. January was the warmest on record, the 44th consecutive January with temperatures above records from the 20th century. Temperatures were 2.7 degrees Fahrenheit above normal in the northern hemisphere, and 1.4 degrees Fahrenheit warmer in the southern hemisphere. In the United States, several states experienced below average snowfall and precipitation. February continued the trend – measuring an average of 2.4 degrees Fahrenheit warmer than usual, making this one of the warmest winters ever.

This news rides on other drastic climate news from around the world, including 65-degrees in Antarctica and wildfires in Australia.

Perhaps most notably, this warm winter was not preceded by a strong El Niño event. El Niño, an ocean-atmosphere climate event resulting in ocean warming, has often been tied to warmer Januarys such as in 2016. The four warmest winters have occurred since 2016.

NOAA scientists predict this record-breaking winter could precede a record-breaking year. The southwest is expected to be dry and experience drought, and Alaska is also predicted to have a warm year. In some areas, springs could be wetter and summer temperatures could arrive earlier.

Scientists have repeatedly warned about climate tipping points, events that lead to severe consequences, arguing society needs to take directed action to avoid future catastrophe. Warm winters have already led to cascading effects, such as wildfires in Australia and record temperatures in the Arctic. It’s no longer enough to meet expectations. As the report warns, “international action — not just words — must reflect this.”