Lab Notes

Short stories and links shared by the scientists in our community

Stressed out crabs don't camouflage very well

The noise from passing ships stresses out crabs and makes them easy prey

Wikimedia

Man-made noise negatively impacts a multitude of animals, including birds, whales, and, as it turns out, crabs.

Shore crabs, or Carcinus maenas, can change the color of their shells to better match their surroundings, camouflaging efficiently against rocky shores. In a new study published in Current Biology, Emily Carter and her team at the University of Exeter show that juvenile shore crab exposed to ship noises don’t camouflage very well.

In this study, crabs were brought to the lab and exposed to three treatments: a neutral control of natural underwater sounds, ship noises, and a loud control consisting of natural noises with the same amplitude as the ship noises. All crabs were dark brown when they first arrived. After eight weeks, both control groups were much lighter in color, matching their background in the lab. The ship noise group, however, remained markedly brown.

Shhhh quiet

The researchers then tested if these poorly camouflaged crabs were at least good at running away from predators. Another surprise: when faced with a simulated bird flying overhead, crabs exposed to ship noises were slower to retreat, and sometimes didn’t even flee at all.

Carter and her collaborators suggest that the stress of being exposed to ship noises hinders the crabs’ ability to change color, as well as their anti-predator fleeing behavior. If crabs exposed to ship noises do indeed become easy prey, crab populations may have a grim future ahead.

Most studies on the impacts of man-made noise focus on species that communicate through sound. What shore crabs are telling us is that the consequences of man-made noise can be much broader than a drowned dialogue.

Sanguine glimpses of positive environmental change on pandemic-Twitter

Homebound humans allow Mother Nature to stretch her legs, but that doesn't mean our current situation is a good thing

Amidst the daily COVID-19 news and press conferences, travel restrictions and hospital case reports, there are some silver linings making the rounds on Twitter.

Nature seems much better off with humans stuck at home.

To be clear, a pandemic is not the solution to climate change. Locking ourselves away for the foreseeable future does not even remotely resemble a solution, and we have the technology and knowledge to address our environmental issues without widespread human suffering.

But COVID-19 does afford us a peek into what happens when humans take their foot off the gas — literally and figuratively.

Once the crisis gets under control and the dust settles, we should reflect on what it means for our relationship with other Earthlings (and our fight against climate change) when a week of staying a home has such a big impact.

If we just gave nature a little bit more of a chance — work remotely a little more, run errands more efficiently, make some other small changes in behavior — we could do a lot of good.

An important subtlety here is that humans are not intrinsically bad for the planet. But many of the things we do carelessly, like burning huge amounts of fossil fuels to commute, producing plastics and other materials that will never break down, and importing food from the other side of the world because it isn't in season, take their toll.

Maybe we should re-evaluate the systems we rely on in our global society, and how we can adapt them.

How a Scientific Reserve Corps could help us in a pandemic

Training scientists and students before a pandemic hits would keep us prepared for the worst

Scientists everywhere want to help. We are helping, as much as we can. We’re donating lab supplies, skyping about our science with children stuck at home from school, and helping inform the public. Medical and education students are volunteering to care for the children of medical personnel.

But for many of us, we still want to do more. As research labs close, there’s an enormous potential workforce with the skills needed to run diagnostic tests, though many lack formal certification. Some opportunities are appearing, including a call for volunteers at University of Washington and the University of California at Berkley, and increased hiring by private companies. Michael F Wells, a postdoctoral fellow at Harvard, is creating a database of scientists who want to help. While that’s a step in the right direction, it can take quite a while for new volunteers to get up to speed. For example, a call-out from the Innovative Genomics Center at UC Berkeley cites a two to three week training period — precious time in a pandemic. In a pandemic, weeks matter.

This likely won’t be the last epidemic or pandemic. It may be worth investing in a system of training for these situations. While a Medical Reserve Corps does exist, the corps focuses on the medical and public health aspects of potential emergencies, without a specific role for scientists.

Scientists and students could be valuable help on the front lines. An organized, nationwide “Scientific Reserve Corps” could help. Scientists and students could complete training (and mandatory refreshers) on how to perform a variety of common tests, many of which could be similar to tests from their own research. They could train in collecting samples with proper PPE, analyzing data and data-sharing. For this to work, a Scientific Reserve Corps could encourage governments to plan for specific needs — coordinating types of test kits, extraction kits, and software — so that people could train before pandemic hits.

With financial aid or compensation, this reserve system could also help students, who often struggle to make ends meet, The motto of the army reserve is “twice the citizen.” Perhaps it’s time for twice the scientist.

Could chronic joint pain improve with changes in sex hormone levels?

Long-term contraceptives could be used to treat people with Ehlers-Danos syndromes

Ehlers-Danlos syndromes (EDS) are a group of rare hereditary chronic diseases which cause collagen deficiency in the body leading to weakness of connective tissues that support the joints, organs, bones, and skin. People with EDS experience a wide range of symptoms and other conditions including chronic pain, bleeding disorders, migraines, and high-risk pregnancies. Recent research suggests that early gynecological care and elective hormonal treatment for people with EDS might help improve their quality of life.

Previous research had shown that people with EDS report worsening of chronic pain and ligament weakness at particular times: during puberty, after giving birth, and prior to menstruation. That link suggests a possible association between EDS symptoms and hormonal levels. For instance, the levels of the hormone progesterone increase during the luteal phase, which begins after ovulation and ends at menstruation. Existing hormonal contraceptives are already known to regulate progesterone levels, so scientists have considered using these drugs to help young people with EDS. Unfortunately, these medications may clash with other conditions associated with EDS, potentially leading to decreased bone mineral density and increased blood clot formation.

In the more recent study from the University of California San Francisco-Fresno and Baylor College of Medicine, researchers evaluated the menstrual information, gynecological complaints and prescribed interventions from medical records spanning 10 years for 26 patients aged 12 to 16. Their findings suggest that the long-term reversible contraceptives such as intrauterine devices (IUDs) could be an option for patients with EDS. But other options less invasive than IUDs may also work. The authors note that referring more children and teenagers with EDS to gynecological care could make a big difference in giving them better treatment.

We need further research on EDS because of how detrimental the disease can be. Due to the associated complications of EDS, it is important to consider what types of contraceptives to use. Collecting information on treatments brings promise to the possibility of controlled studies testing different hormonal treatments to manage EDS symptoms.

Keep coronavirus from spreading in Hawai'i. Cancel your vacation

It would be selfish to imperil Hawai'i's health with a cheap flight

Photo by Cosmin Serban on Unsplash

Scrolling through Instagram past the warnings to stay home due to COVID-19, you see it.

A $49 flight deal to Hawai'i. “Your office at the beach!" The ad paints a serene image of waves crashing while you answer emails and sip Mai Tais. What this ad doesn’t show are the estimated 227 licensed acute critical care beds available in the entire state (as of 2018), with some islands having only 9 and Hawai'i island, the second largest island in terms of population, having only 24 beds. With a population of 1.4 million residents, these 230 ICU beds will go quickly and those in more remote islands will be left without care should COVID-19 spread. Add to this the fact that 140 acute care beds were reported as unstaffed in 2018, and this paints an even more dire picture of how strained Hawai'i’s healthcare system will be should the pandemic take hold in the state. In times of panic and pandemics, tourist destinations and tropical paradises are hit hardest. They will hesitate to close ports and airports as tourism is the primary source of income and livelihood. That is why you must be the one to say no to traveling to Hawai'i. You are directly responsible for the safety of the state.

We talk constantly now of staying indoors to protect our most vulnerable; those immunocompromised or above the age of 60. But just as there are vulnerable individuals, there are vulnerable states and this must rise to our common conscience. Hawai'i is one of them. Compare Hawai'i’s 227 acute critical care beds with California’s 7,274. In concrete terms this means that there are 1.81 acute critical care beds per 10,000 people in California compared to 1.6 in Hawai'i. While the numbers seem small, the impact on Hawai'i’s death toll will not be. Hawai'i is 24% short of the minimum number of physicians required to adequately care for the population. On some islands, such as Hawai'i Island, they are short 44%. Add to this that 25% of the doctors in Hawai'i are over the age of 65, putting them at particularly high risk of serious complications from COVID-19. In addition to an incredibly precarious health infrastructure, Hawai'i is 2,467 miles from the nearest land mass, lending it even greater vulnerability should more advanced care be needed for those that fall ill or should food and supplies run out.

As of Saturday March 21, of the 37 confirmed COVID-19 cases in Hawai'i, only 2 were not attributed to recent travel. It is only a matter of time before a tourist is responsible for the community transmission of a deadly virus that cripples the health of the people of Hawai'i. And if this is not enough to convince you to postpone your vacation, just think how much better a future vacation to Hawai'i will be if the state isn’t ravaged by COVID-19.

(Ed: Governor David Ige has imposed a mandatory 14-day quarantine for anyone returning to or visiting Hawai'i.)

Researchers study the economics of mangroves by looking at nighttime satellite photos

Coastlines with wide bands of mangroves are relatively well-protected from economic downturn after hurricanes

Photo by Aristedes Carrera on Unsplash

Mangroves are pretty incredible. They are the only type of trees capable of living in saltwater and perform a ton of beneficial services for the environment and humans like providing critical habitat to important fish species and reducing the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. Now, thanks to new research published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, we can add “protecting coastal economies” to the list.

Coastal mangrove forests serve as a barrier between oceans and human settlements on land. In the midst of tropical storms, mangroves buffer shorelines from damage by reducing wave action and storm surges. As the strength and frequency of hurricanes increases as a result of climate change, scientists and economists have been wondering just how much economic value these barrier forests provide as they protect us from storms.

To find out, researchers studied how coastal areas in Central America fared during hurricanes from 2000 – 2013. Unfortunately, it can be difficult to get a full picture of the economic impacts of storms so researchers relied on an interesting indicator of economic activity: the appearance and amount of lights visible in an area in satellite imagery at night. More lights in an area equates to more infrastructure and activity, which tends to correlate to higher income and economic activity. By comparing the images of lights in an area before and after storms, scientists were able to judge just how much damage the area had sustained and how long the area was likely facing an economic downturn post-hurricane.

In areas with relatively narrow bands of mangrove forests (less than 1 km wide), there was around a 24% decrease in lighting at night after a category 3 hurricane. But areas that had larger bands of mangroves buffering them from storms were unaffected!

Unfortunately, mangroves risk deforestation from threats like human development, pollution, and overharvesting. While scientists have been trumpeting the phenomenal benefits we receive from having healthy and intact mangrove ecosystems for a while, it is still shocking to see how this service impacts the bottom line for so many coastal communities. When you see the numbers, you really can’t deny how important it is for us to focus on conserving these important habitats.

How to stay calm during a pandemic

We all have very valid reasons to be anxious right now. Here's how to keep your anxiety in check

Photo by Alex Knight on Unsplash

We are currently living in a situation of extreme uncertainty, and if you are like me, you may have noticed yourself feeling extra anxious lately. Maybe you feel a constant ache it in your shoulders and neck. Maybe you are compulsively checking your phone, unable to tear your eyes away from Twitter and Facebook, or maybe you're extra irritable. According to medical professionals, these are very normal responses to the coronavirus pandemic.

Luckily there are lots of things you can do on your own to help ease the stress. Here are a few that work for me personally (note: I am not a medical professional). Not all of these will work for everyone, so don't beat yourself up if you try something to lessen your anxiety and it doesn't do much. Each of us is unique in our experiences and reactions to stressors!

Create something: Make something with your hands. You can cook or bake, put together a puzzle, color or draw, work in your garden or yard (if you have one), or even clean out your car. Whatever you choose, try to really focus on what you are doing instead of letting your mind wander. Don't worry about making something perfect — just enjoy the process!

Go outside or get moving inside: Unless you are currently under lockdown, and assuming you stay at least 6 feet from others, it is safe to go outside. Exercise can help you redirect nervous energy. It also gets your feel-good neurotransmitters flowing. By the way, dancing in your living room counts as exercise!

Step away from your phone: Put the phone down. Leave it in another room while go about your other activities. It will feel weird, but I promise you that logging off Twitter and other social media for half an hour will not harm you. To be clear, your phone isn't the root cause of your anxiety, but a constant barrage of COVID-19 related news isn't helpful, either.

Give yourself a break: If you are really feeling anxious and it is keeping you from your daily activities, try just letting yourself be. A lot of times the pressure we put on ourselves to stay productive, keep working, clean the house, and so on keeps us paralyzed. Banish the word "should" from your vocabulary for now, and just do the best you can. Sometimes just giving yourself permission to slack off is enough to get your motivation and focus back.

Try mindfulness: Mindfulness seems like the hip, hot thing to do lately, but there's a reason for that — it works. There are tons of online resources and apps for learning mindfulness. I am most familiar with Headspace, and the thing I like most about it is that students (including grad students!) can get access to the full app for $10/year (usually $70). There is a lot of material in the app, and in my opinion it's worth it.

If full-on mindfulness isn't for you, but you need a way to stay calm when it feels like the world is falling apart around you, the 54321 method of grounding yourself is a good place to start. Take a deep breath, then look around you for five things that stick out to you in the moment, and say them out loud. Then repeat that with four things you can feel, three sounds you hear, two things you can smell, and one thing you can taste. Then take another deep breath.

We're all in this together. While you may have to stay physically distant from people right now, don't forget to connect socially in any way you can. And if you are feeling totally overwhelmed or depressed, please reach out to a mental health professional.

What happens when a scientist investigates results that are "too beautiful to be true"?

Inside Tsuyoshi Miyakawa's attempts to improve reproducibility in science

Photo by David Clode on Unsplash

Some fields of science are currently experiencing a reproducibility crisis. This means that a large number of scientific studies, that have been peer reviewed and published, cannot be repeated with the same results. One of the causes for this is scientific misconduct. This may include p-hacking, the practice of adding in data until the results are significant, selective reporting, where only the desired results are shared, or outright falsification of data.

The Editor-In-Chief of the journal Molecular Brain, Tsuyoshi Miyakawa, recently wrote an editorial in which he examined the manuscripts he had handled over the last two years. As an editor, his job is to judge whether a manuscript is good enough to send to reviewers. In some cases he might decide to ask the authors to provide the raw data before sending it out for review, especially if the results look ‘too beautiful to be true.’

Over the two years of manuscripts he analyzed, Miyakawa sent out requests for the raw data 41 times. He only received data in 20 cases. In 19 out of those 20 cases, the data was either incomplete, or did not match with the results in the manuscript. The reason why in so many cases the raw data was not available or incomplete is not clear, but it might suggest that this data never existed in the first place.

Miyakawa calls for increased availability of raw data. His journal, Molecular Brain, now requires the raw data for every manuscript submitted to be made publicly available. This makes it easier to determine whether results are genuine, and it will increase transparency. Although the reproducibility crisis is complicated and will not be solved completely with just this requirement, it is definitely a step in the right direction.

What does social distancing really mean?

Everyone needs to be socially distancing themselves right now. Here's what you should know to protect yourself and others

Photo by Priscilla Du Preez on Unsplash

After the World Health Organization (WHO) declared that the coronavirus outbreak is officially a pandemic, countries around the world have responded accordingly. Universities in Canada and the US are closing, non-essential conferences and sports leagues are being canceled, and people are being advised to halt all travel plans. Anyone can get infected, and the only way to slow down the outbreak is to reduce the number of people getting infected.

Amidst this fear, the most widespread advice for anyone experiencing symptoms is to socially distance themselves. But what, exactly, does that mean? How is this different from self-isolation? What if you live with family? What if only one person in a family of four is experiencing symptoms? Why is this even important?

How do I know if I need to socially distance myself? How is that different from self-isolation and strict isolation?

Everyone should be socially distancing themselves! Essentially, that means deliberately distancing yourself from other individuals to reduce COVID-19 transmission rates.

On the other hand, self-isolation or self-quarantine is when you have been in contact with someone who was diagnosed with the coronavirus, or someone who was exhibiting symptoms. Self-isolation also applies for people who are asymptomatic, but have secondary medical issues (diabetes, heart condition) that may make a coronavirus infection more dangerous for them.

Lastly, isolation is when you have been diagnosed with COVID-19, or if you are exhibiting any flu-like symptoms. At this point, you will receive instructions for isolation from your medical provider.

What does social distancing entail?

If possible, do not leave the house. Try to stay at least six feet away from other people, and avoid coming in direct contact with them. Social distancing can also be done by avoiding crowds and mass gatherings, canceling upcoming events, working from home, moving classes online, and communicating electronically instead of personally visiting people.

What if I live with other people?

Even if no one in the household is exhibiting symptoms, it is best to keep distance for at least two weeks, which would be the virus’s incubation period. On the other hand, if you need to self-isolate, try to sleep in separate rooms, and keep 6 feet away from each other. Frequently wash your hands, and frequently keep your surrounding areas clean. If possible, avoid touching your face, especially after being in contact with shared possessions or furniture. Wash all plates and utensils thoroughly with warm soap and water, or use a dishwasher with a drying cycle.

How can I help vulnerable people?

If there are vulnerable and at-risk individuals in your neighborhood, consider getting groceries and other essentials for them, and leave the items at their doorstep. Frequently call or check up on your friends and family, since social distancing can be quite lonely.

Why is social distancing important for everyone, including young and asymptomatic people?

According to data from South Korean authorities, translated by Dr. Eric Feigl-Ding, young people between the ages of 20 and 29 are carrying 30% of the disease in South Korea, with the majority being asymptomatic, meaning they are not experiencing symptoms. This means that while you may feel fine, if you are sick you can still infect a large number of people by just being out and about!

Why is social distancing important?

By now you have probably seen a version of the graph that explains why we need to "flatten the curve." Through social distancing and pro-active measures, we can not only delay the "peak" of the outbreak, easing demand for hospital and emergency services, but can also reduce how bad the outbreak could be.

Do you still have questions about social distancing, isolation, or anything else about the coronavirus pandemic?

👇Ask our community of scientists now! 👇

Good news for people with tattoos: your skin still works

Research shows that tattooed skin functions just as well as non-tattooed skin

Anna Shvets from Pexels

Do you have a tattoo and ever wonder if your tattooed skin is any different from your non-tattooed skin? Are you just now reading this wondering if this is something you should be wondering about?

Skin is your body’s first defense against pathogens and works best when it is intact. Tattoos break that defense by using tiny needles to deposit granules of permanent ink directly into the skin. Tattooed skin heals over time, but researchers in Denmark and the Netherlands wondered if the function of tattooed skin would be permanently altered compared to non-tattooed skin.

They tested this possibility on 26 tattooed individuals of varying ages and varying tattoo ages (meaning, the number of years it had been since their tattoo(s) were done). By measuring a number of different skin parameters, such as pH and conduction, the researchers were able to understand skin barrier function in the tattooed and non-tattooed areas of each person. They found no differences between tattooed and non-tattooed skin for each measurement except capacitance, is a measure of skin hydration that was increased in tattooed skin. That higher capacitance suggests that tattooed skin is more hydrated in deeper layers than non-tattooed skin. The researchers aren’t sure why tattooed skin would have higher capacitance, but they suggested that a larger study could get to the bottom of this question.

In the meantime, they did conclude that the skin barrier gets fully restored after a tattoo. So if you have a tattoo, you can rest assured that it looks great and has no impact on your skin’s function.

This fish parasite can power itself without oxygen

Meet Henneguya salminicola, a tiny animal that has upended our understanding of animal biology

Photo by U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service via Flickr

Imagine this: you're sitting outside your high school biology class cramming for an exam. The topic is aerobic respiration. "The process of using oxygen to create energy that powers the living cell," you mutter to yourself. Aerobic respiration takes place in the mitochondria, and it is why animals — including us — need oxygen. Whether we breathe it in, extract it from water through gills, or absorb it through the skin, we all need it.

Or so we thought. But brand new research has upended that assumption. Scientists recently discovered a parasite that lacks mitochondria and so cannot use oxygen to power their cells.

Let me introduce you to Henneguya salminicola. H. salminicola is a member of the phylum Cnidaria. You might be familiar with a few other Cnidarians, such as sea jellies and corals. However, H. salminicola belongs to a group of parasitic animals called Myxozoa. Their hosts include salmonid fishes, such as salmon, trout, and other freshwater fish.

When the researchers examined the parasite's genome, they didn't find any evidence of mitochondria. And when they looked at its cells under a microscope, they found cristae, a structure that resembles the inner folds of mitochondria, but doesn't perform the same way. This suggests that the lack of a mitochondrial genome in H. salminicola is not a very old trait. Instead, they speculate that the loss of mitochondrial DNA may be a recent event in this organism's evolutionary history.

Although this discovery upends what we knew about animal biology, it also makes sense. Salmon muscles are low-oxygen environments, and so over time H. salmonicola apparently lost its ability to power itself with oxygen. But what makes this discovery so cool is the proof of a possibility. Multicellular life can exist without oxygen. Where else on Earth and in space could they be thriving?

Science games and challenges to pass the time while you are stuck at home

Here are some ways to kill boredom – and contribute to scientific research – while you're doing your part to flatten the curve

Photo by Tobias Adam on Unsplash

If you are newly stuck at home with science-minded kids, or are just looking to add another website to your internet routine in this time of social distancing, here's a list of educational and productive science games that might come in handy. If you have a favorite that doesn't show up here, send me a link on Twitter and I will add it.

FoldIt: We wrote a great article outlining one of the major scientific discoveries made with this protein-folding game a few months ago. Try it yourself – there are even coronavirus puzzles that you can do, if you want to take out your stress on (a virtual copy of) the virus itself.

Zooniverse: This site has an enormous range of projects you can contribute to. You can do everything from helping scientists classify bird breeding behavior on NestCams, to identifying wildlife from camera trap photos as part of Snapshot Ruaha, to locating black holes on Radio Galaxy Zoo. There is truly something for everyone!

March Mammal Madness: The basketball version of March Madness has been canceled, but this animal-themed competition is still going. Although several battles have already been fought, it's not too late to fill out a bracket (assistant editor Max Levy is cheering for the Australian feral camel to win it all!). You can catch up on the competition and get some great science content — complete with references to peer-reviewed research — on the competition's Twitter feed.

Kerbal Space Program: This is co-founder Allan Lasser's pick. In this fictional game you are the leader of a space program for an alien race called the Kerbals, and you get to construct spacecraft, perform space experiments, and even make budgeting decisions for your organization (because funding science is important). This game would be great for kids who want to learn physics and astronomy alongside some real-life space scientists.

Eyewire: In this game, your goal is to map neurons in the brain. You are presented with a cross-section of a real brain map, and your job is to trace a neuron through that cross-section. Consortium member Dori Grijseels, who sent me this suggestion, calls it "weirdly addictive!" If you're interested in the science behind the game, here's a TED talk by the game's director.

Ocean acidification will eat away at the shells of abalone and other economically important shellfish species

Scientists uncover yet another negative impact of climate change on the world's oceans

24hseamart on Pixabay

As carbon dioxide emissions dissolve into the oceans, seawater carbonate (CO3) concentrations decrease. In the future, low CO3 concentrations will threaten the survival of ecologically and economically important shellfish, as they struggle to find enough carbonate to build their calcium carbonate (CaCO3) shells. With these concerns in mind, a study published in December of 2019 in the journal Marine Biology looked at how juvenile abalone (Haliotis tuberculata), a type of sea snail, are affected by low carbonate seawater.

To examine how low seawater carbonate affects abalone physiology, researchers cultured six-month-old juvenile abalones for three months in seawater with various levels of CO3, representing current and predicted near-future conditions. They measured and compared survival and growth of the abalone, as well as the micro-structure, thickness, and strength of their shells, across a range of CO3 concentrations.

After three months of exposure, they found that the lowest seawater CO3 treatment significantly reduced the length, weight, and strength of the abalone shells. Through scanning electron microscopy, they also observed that low CO3 resulted in more porous shells with modified textures.

These findings confirm that low CO3 levels in seawater make it more difficult for H. tuberculata to build their shells, resulting in slower growth and increased shell corrosion. Abalone and other shellfish are hugely economically and ecologically important, and this study reveals yet another projected negative effect of climate change on the world's oceans.

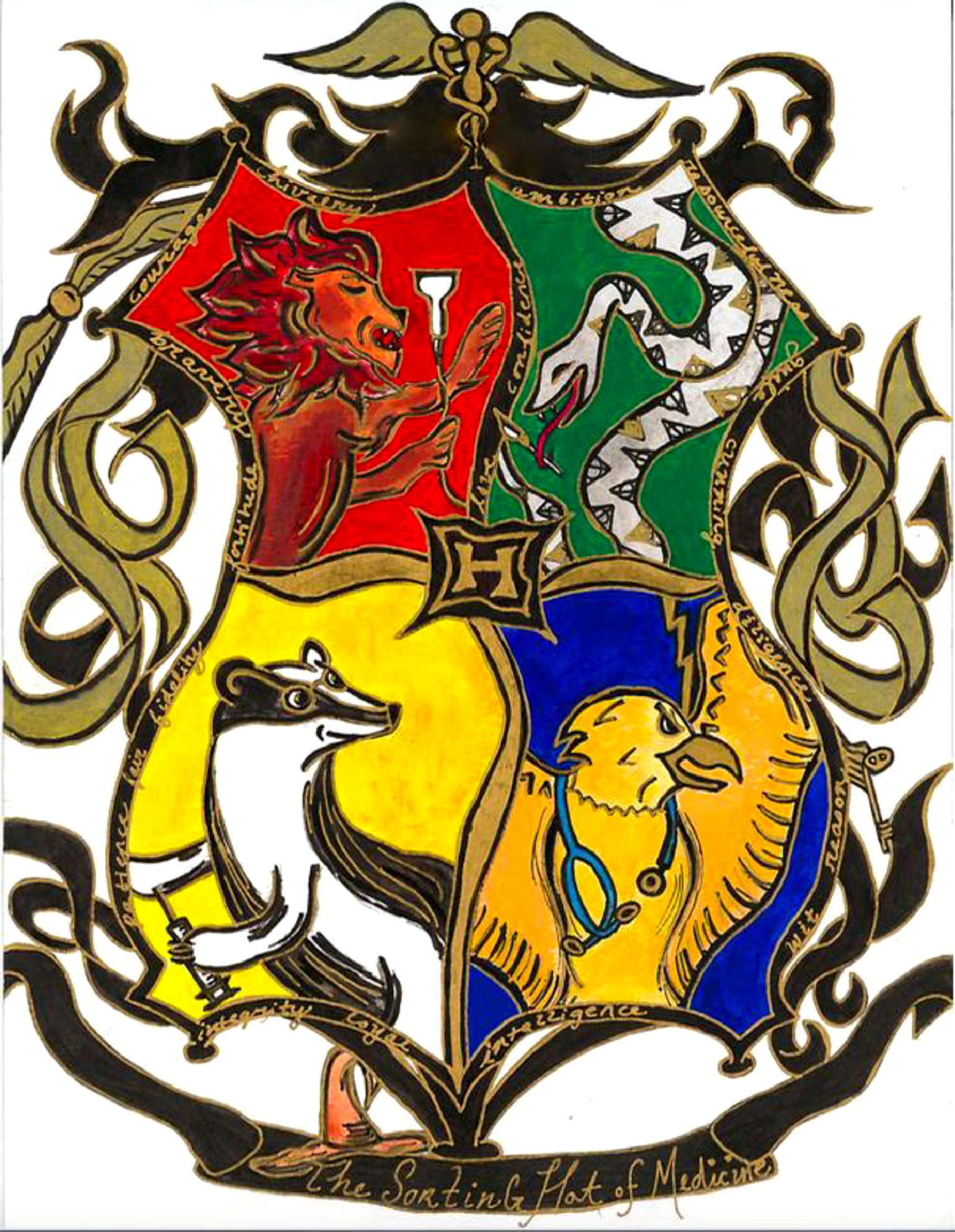

For medical students who can't decide which specialty to pursue, maybe a Sorting Hat is the answer

Two physician-scientists surveyed 251 medical residents about their current medical specialty and which Hogwarts house they belonged to

Photo by Artem Maltsev on Unsplash

One of the more important decisions that medical students make in their careers is which specialty to pursue. Unlike the world of Harry Potter, there is no magical Sorting Hat to peer into the thoughts of medical students and sort them into the ‘right’ specialty. But that didn’t stop two physician-scientists from considering what a “sorting hat of medicine” could look like.

In a new study published in the Journal of Surgical Education, Maria Baimas-George and Dionisios Vrochides surveyed 251 medical residents about their current specialty and which Hogwarts house they belonged to. The study – which is delightfully titled The Sorting Hat of Medicine: Why Hufflepuffs Wear Stethoscopes and Slytherins Carry Scalpels – attempted to identify whether specific specialties attracted particular personalities.

In case you need a refresher on JK Rowling’s fictional world, Harry Potter and his fellow magical students attend the Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry. In their first year, students are sorted via a Sorting Hat into four distinct houses: Gryffindor (for those with “daring, nerve and chivalry”), Hufflepuff (just, loyal and “unafraid of toil”), Ravenclaw (“those of wit and learning”) and Slytherin (“cunning folk [who] use any means to achieve their ends”).

A visual representation of the prized attributes of the 4 Hogwarts houses and the medical specialties they may correlate with

Maria Baimas-George

Together, Baimas-George – a long-time Harry Potter fan – and Vrochides created a six-question survey to ask participants about their specialty, and which Hogwarts house they would self-sort themselves into. In another nod to the Harry Potter novels, respondents who knew about Harry Potter but didn’t select a house were classified as Muggles.

A total of 251 medical residents responded to the survey. Around half (49.4%) of the survey respondents were surgical residents, while the remaining non-surgical residents belonged to specialties including pediatrics, gynecology and family medicine. Interestingly, Baimas-George and Vrochides found that there were more Slytherins, and fewer Hufflepuffs, in surgical compared to non-surgical specialties. There were significantly more Gryffindors and fewer Hufflepuffs in general surgery, and more Slytherins in orthopedic surgery. (Fun fact: Baimas-George is currently a general surgery resident and a Gryffindor, but acknowledges a few Slytherin-esque traits too.)

Wondering where all the Hufflepuffs and Ravenclaws are at? Me too. It turns out that there were significantly more Hufflepuffs, and fewer Gryffindors, in pediatrics. Ravenclaws showed up in greatest numbers in gynecology (35.3%) compared to other specialties (19.9%), though this wasn’t a significant difference.

Oh, and there were no Slytherins in family medicine.

Based on these findings, the authors conclude that certain personality traits may be more useful or essential in specific specialties. For example, Slytherin values – such as ambition, power, and cunningness – do match those seen in residents pursuing surgical specialties. And past studies show that surgery students tend to be more determined, have higher self-confidence and are less anxious.

Despite its small sample size, this study does suggest that Hufflepuffs are more likely to wear stethoscopes and that Slytherins are likely to carry scalpels. Perhaps medical students should also consider Harry Potter’s Sorting Hat when it comes to deciding which future specialty to pursue – but they shouldn't forget to consult mentors, friends and loved ones first.

The iconic Colorado River carries less water, as the climate warms and winter snow disappears

New research quantifies water scarcity in the southwestern USA: expect more drought, with serious socioeconomic consequences

Photo by David Lusvardi on Unsplash

One of the most socioeconomically important impacts of climate change is drought. In the southwestern U.S., water scarcity is has been a concern for decades. We've seen wildfires, dried-up riverbeds, and crop failures in part as a result of droughts and less snowpack, and many cities in the southwest are already restricting water consumption based on these issues.

Perhaps the most visible and historic story of water use and climate change is that of the Colorado River. Stretching from Colorado and Wyoming to (historically) the Gulf of California, it has long been the water source of the west. But since the late 1990s, its southernmost riverbed — including the outlet to the ocean — has been dry as a result of damming, increased water consumption, and climate change.

We know that the Colorado no longer reaches the ocean (with the exception of an experiment in 2014 that let it flow freely), but what's harder to pin down is how exactly climate change is affecting its discharge rate (how much water it's moving). A new study in Science has found that per degree Celsius of warming, the river's mean annual discharge has decreased about 9% — undoubtedly contributing to water scarcity in the southwest. In their models, they found that the loss of winter snow, which reflects heat back up to the atmosphere when it is present on the ground, led to warmer temperatures and more evaporation.

The authors found that even if precipitation increases in the areas where the Colorado River collects its water, it likely won't be enough to offset the increased evaporation as a result of the warming. Predicting more severe water shortages, this study offers a dire warning of the consequences of climate change, especially for regions like the southwest that are already stressed.

Scientists outfitted cuttlefish with 3D goggles to understand how their brains perceive depth

Humans aren't the only animals that can see in three dimensions, but not all animals perform this feat in the same way

Pawel Kalisinski on Pexels

Seeing in 3-D and perceiving depth (called stereopsis) is a very complicated process. Each of your eyes sees a single 2-D image, but because our eyes are positioned to see that object from slightly different angles, our brains can use this disparity to perform some quick mental geometry and figure out where an object actually is in space. You can get an idea of this disparity between the images seen from each of your eyes with this quick test.

But our way is not the only way to see 3-D objects and perceive depth. In fact, over the years, we have found that more and more animals – cats, horses, birds, and even some insects - are capable of perceiving their world in three dimensions. Not all of them rely on the same mental algorithms we do. Learning more about which animals can see in 3-D and how their brains process this information can tell us more about why 3-D vision and depth perception has evolved in different groups of animals. It might even be able to give us new ways to teach machines to visualize 3-D objects.

Cephalopods (octopus, squids, cuttlefish, and nautiluses) have surprisingly similar eye anatomy to humans, despite the fact that we have drastically different evolutionary lineages and live in wildly different environments. But our brains and the way in which we process the information from those similar eyes, is far from the same. Scientists from the University of Cambridge and the University of Minnesota were curious to see how a cephalopod brain processes visual information, and how it compares to our own mental algorithms. So they outfitted a cuttlefish, a type of cephalopod, with 3-D glasses!

3-D glasses use polarized filters to show each of your eyes the same object from slightly different locations, tricking your brain into perceiving a 3-D object. With this approach, the scientists were able to test if cuttlefish altered their response to images of prey based on the disparity between images being shown to their right and left eyes. They discovered that cuttlefish do perceive 3-D images and use their depth perception to improve their hunting efficiency. However, the results from the study suggested that cuttlefish brains likely use a completely different algorithm to perceive depth.

The more we find out the difference in these visual algorithms could teach us a lot about how vision evolved across the animal kingdom and how we can make use of these algorithms for machine learning.

Hands-on learning makes STEM students more scientifically creative

Free-form makerspaces help young scientists develop skills not found in traditional classrooms

SLUB Presse2015 on Wikimedia Commons

Perhaps your local library has one, or maybe your local university does. Makerspaces are even popping up in places like elementary schools and museums, including the FabLab of the Museum of Science and Industry. Makerspaces, which are open creative spaces featuring objects such as 3D printers, laser cutters, and woodworking tools, have become a buzzword for hands-on learning.

Teachers and administrators are scrambling to bolster learning that increases competency in subjects such as math and engineering. This is especially true in subjects that require a heavy amount of memorization and theory, such as math.

Now, according to researchers in British Columbia, subjects who participated in a class at a university makerspace, complete with project-based learning, helped participants within post-secondary education in understanding not only how to create a product, but also the social skills behind them as well, such as selling the final product. This was because this form of STEM learning requires not only the creative process of design, but also the creation of a final project that can be used in the real world, such as a new brake on a wheelchair or a cup holder.

With research conducted on undergraduate university students within engineering, those who participated in doing their work felt more confident and able in their engineering skills.

Children that go to school near major roadways experience more severe asthma

New research reiterates that air pollution is a public health risk, and that children in cities are particularly at risk

Photo by Marcelo Cidrack on Unsplash

The correlation between pollution and lung health, particularly asthma, has been suspected since the industrial revolution, when cases of lung and respiratory illness skyrocketed with the rate of air pollution. A 2020 study by a group of researchers at Harvard Medical School has now looked at the many socioeconomic factors that come with this discovery in present day cities. For example, lower income families tend to live closer to major roadways, in densely populated cities, in regions with higher pollution.

The study surveyed children living with asthma in urban northeastern American schools living in inner-city areas. The homes and schools of the children studied were mapped and their proximity to major roadways measured. The likelihood that a child experienced asthma symptoms, and the frequency that they experienced them, was shockingly different between children in schools close to major highways and those further away.

In fact, for every 100 meters further from major roadways (in terms of school location), children were 29% less likely to report asthma symptoms in general, including need of an inhaler and asthma attacks. These results show us that children attending school near major highways, which are increasingly numerous across North America, have higher asthma rates and more severe symptoms, compared to students who do not go to school near major roadways.

Pollution is hard on our lungs, particularly when an underlying condition such as asthma is present. This study implies that more attention needs to be given to children attending school in inner-city, traffic-heavy districts, including monitoring of their lung health and asthma progression. These studies are difficult to perform because so many factors, such as socioeconomics and genetics, can also influence asthma and lung health, there is rarely a clear and direct cause-and-effect relationship. But, studies like this pave the way for future findings and improvement of conditions for asthmatics in city centers around the world.

Elderly patients are being excluded from breakthroughs in diabetes science

We need more inclusivity in research, and technology geared towards older patients.

Photo by Matthias Zomer from Pexels

Recent advances in technology have paved the way for better diabetes management. Innovations, such as glucose tracking apps, sensors, and fitness bands give people with diabetes more control over their health. But not everyone is benefiting equally – older patients are still excluded due to a lack of evidence-based studies.

Diabetes ranks seventh among the top 10 global causes of death. Up to 90 percent of people with diabetes have Type 2 diabetes, a biological disaster that has reached epidemic proportions in the United States, as well as in India, China, and elsewhere. The condition is more prevalent in aging populations, but the extent to which older people are affected is still unclear. Much of the data either omit the elderly or do not separate by age. Without this data, we may not properly understand the needs of older patients, or how to best treat them.

A major challenge when dealing with diabetes in older patients is that many simply don’t know their diabetes status. This is strongly linked to the lack of evidence-based studies. Low awareness among older adults is linked to difficulties in screening, diagnosis, and treatment abilities. As health systems continue to evolve, technological innovations can play a role in improving the quality of life of older people with diabetes, whether they know their status or not. These innovations can prevent potentially severe complications, such as heart attacks, kidney failure, blindness, and amputations, any of which can begin as seemingly harmless symptoms. If designed properly and with inclusivity for older patients in mind, we won’t run the risk of leaving anyone behind.

Type 2 diabetes is a serious global concern. It is paramount that societies raise awareness of diabetes status, collect data for people of ALL ages, and invest in science to reduce the global burden of this epidemic.

Could drinking hydrogen help people with asthma?

A new study shows how hydrogen tinkers with cells to reduce inflammation

Tim Mossholder from Pexels

My first encounter with ”hydrogen” gas was on my 4th birthday. I was amazed at what the gas could do to regular boring balloons. Since hydrogen is lighter than air, my mom told me, it makes balloons levitate. Although helium supersedes hydrogen because of hydrogen’s explosive nature, all I remember was that it added a serene feeling to my birthday party. Turns out that hydrogen can add calm to more than just birthday parties, but people with asthma too!

Research on hydrogen-based therapy has gained popularity in the past ten years because of hydrogen’s newly discovered antioxidant properties. We’ve known that hydrogen molecules can enter our cells and eliminate damaging “oxidant” molecules like free radicals. Those oxidants could otherwise cause inflammation or damage the body. Now, a recent study claims that hydrogen is able to alleviate inflammation, such as allergic asthma. The study suggests that hydrogen works by “reprogramming” how allergy-causing immune cells produce energy.

To better appreciate the anti-allergic role of hydrogen, it is important to understand how immune cells cause allergy symptoms in the first place. A normal healthy cell produces energy by a long yet efficient pathway called oxidative phosphorylation. However, cells from asthmatic patients switch to a different pathway that produces energy quickly but inefficiently. That process actually produces lactic acid – the same acid that makes your muscles hurt when working out. Hydrogen steps in and reverts the allergy-causing cells to using the more efficient, beneficial pathway – reducing inflammation.

To see this in action, scientists injected hydrogen-rich saline into asthmatic mice. By measuring a reduction in the amount of lactic acid, the group showed that hydrogen apparently reduced airway inflammation.

It is remarkable that something as simple as molecular hydrogen can reduce asthma. Just imagine the improved quality of life of asthma patients upon drinking hydrogen infused water or Gatorade without having to spend money on prescription drugs.

Are some of us hard-wired for compulsive drinking?

Brain activation can predict compulsive alcohol consumption (in mice!)

Photo by Wil Stewart on Unsplash

The persistent use of alcohol despite the negative consequences is widely accepted as one of the main behavioral traits in alcohol use disorder, and has also been considered as one of the more promising points of intervention. Despite the acknowledged importance, the neural correlates of compulsive drinking are not well understood.

But progress is being made. A sophisticated study recently identified a neural circuit in the mouse brain, the activation of which could be used to predict the emergence of compulsive alcohol consumption.

Tiia Monto on Wikimedia Commons

The researchers developed a new model where the mice first got to drink alcohol in small dispensed servings. Next, the mice got unlimited access to alcohol for few hours a day, for five consecutive days a week, leading to binge-like drinking behavior. After this, the mice were returned to the original setup with the smaller alcohol servings. Bitter-tasting quinine was then added to the alcohol in increasing concentrations, making the alcohol more unpleasant. Afterwards, the mice were categorized into three groups based on their drinking behavior. Low drinkers didn't drink very much alcohol. High drinkers drank lots of alcohol, but drank much less when the nasty-tasting quinine was added. Compulsive drinkers drank a lot, even when it tasted terrible.

The scientists then identified a neuronal pathway leading from the cortex to an area of the brainstem called the periaqueductal gray, and measured the activity of these brain cells during the first time the mice were exposed to alcohol. Remarkably, the activity patterns of these cells during the first phase of the test were strongly correlated with the drinking behavior in the post-binge phase. In other words, the brain activity patterns that the mice showed when they were first exposed to alcohol predicted which mice would later become compulsive drinkers.

While the clinical applications are not exactly right around the corner, it's possible that these results may be able to inform future treatments for alcohol use disorder.

Coronavirus forces the world's largest physics conference to cancel its annual meeting

The public health decision is getting mixed reactions

Photo by Carlos "Grury" Santos on Unsplash

On the eve of one of the biggest academic conferences of the year – the American Physical Society’s March meeting — the attendees received an urgent cancellation.

Conferences like this one are an opportunity for scientists from a wide range of disciplines and geographies to share their advances, network, and even find jobs. In fact, I was scheduled to drive down from Boulder on Wednesday to present my recent work with nanoparticle antibiotics.

APS appears to have been in constant contact with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Just five days before cancelling, APS issued a statement that the meeting would proceed, citing that “the CDC indicates that the immediate health risk to meeting attendees is low.”

But the threat to public health is very real. According to APS, the decision was based on growing numbers of infections, and “the fact that a large number of attendees at this meeting are coming from outside the US, including countries where the CDC upgraded its warning to level 3.” APS plans to reimburse registration fees, but airlines and hotels refunds may require some more work.

This isn’t the only conference to change plans in response to the novel COVID-19. The CERAWeek energy conference in Houston cancelled and Game Developers Conference postponed its San Francisco meeting.

Some disappointed attendees are using the opportunity to make lemonade — encouraging scientists to share their work online for a “virtual meeting.” (Not the worst idea, considering the climate crisis). APS has since endorsed the idea and plans to compile the presentations.

As CDC catches up from early errors with diagnostic kits, we may continue to see reported counts rise, conferences cancel and (of course) angry tweets.

Attention, birders! A new tool can help you automatically identify birds you spot, no field guide needed

This "digital guide" is the product of a collaboration between the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and Swarovski Optik

Walton LaVonda, USFWS on Pixnio

I am terrible at identifying birds. Terrible. I can handle the trees of the Andes, but as soon as what I'm looking at starts moving, I struggle to spot all of the relevant identification details. Usually by the time the bird has flown away, I've barely even been able to see what color it was! That's why the debut of a new tool from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, in collaboration with Swarovski Optik, caught my eye.

The tool, called a "digital guide," is a monocular, which functions similar to binoculars, but consists of just one tube. After you spot a bird through the lens, you can take its photo, which the guide then sends straight to your cell phone. Then, with the help of Cornell's Merlin bird identification app, it automatically returns a list of birds that might be what you are looking at. The integration of this amazing technology is the latest example of the "gamification" of nature, allowing anyone with the digital guide quickly identify birds and add new species to their lifetime list.

This could level the playing field for people who want to start observing nature but lack the background knowledge to identify what kinds of birds they are seeing. It could also standardize data collection by field scientists, which would particularly be a welcome tool in tropical countries with high bird diversity.

But one variable remains unknown: the price. If the digital guide is too expensive, it will only be accessible to wealthy folks and the most well-funded researchers. And for many casual nature observers, the pleasure of just being outside without technology may be a key reason they find birding so relaxing. So, don't throw those bird identification books out just yet!

Or if you do, can you send them my way?

CDC confirms three person-to-person cases of coronavirus in the United States

The number includes a patient in Sacramento County, California, but it does not include 44 people from a cruise ship quarantined in Japan

CSPAN

There are three cases of person-to-person transmission of SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19, in the United States, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). This includes a patient in intensive care in Sacramento County in California, but it does not include 44 people from the Diamond Princess cruise ship that have tested positive. A British man who was also quarantined on the ship recently died, bringing the ship's death toll to six.

The CDC announced the California case late Wednesday. How this patient came in contact with the virus is unknown, as they had not traveled anywhere the virus is in outbreak and had not knowingly come into contact with anyone who had traveled. Nancy Messonnier, Director of the Center for the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases (NCIRD), a department within the CDC, said that they are expecting to monitor family members of the patient and health care workers who came in contact with the patient for spread of the virus.

Yesterday, Representative Ami Bera (D, CA-7), who represents parts of Sacramento County near to where the patient is, said that there was a four day gap in the federal government's response to a request from local medical officials for COVID-19 testing for the patient. The CDC reiterated their claim that they were first contacted on the 23rd, as opposed to Rep. Bera's claim that Sacramento County officials contacted them on the 19th. The CDC stated that they received samples from the patient on the 25th and confirmed the presence of the virus on the 26th. No explanation for the discrepancy was offered by the CDC.

The CDC expressed confidence that aggressive border control played a part in keeping US cases low. California governor Gavin Newsom said that they are monitoring 8,400 people for presence of the virus and have only 200 kits available to make confirmatory diagnoses.

Kits made available by the federal government to diagnose COVID-19 use the polymerase chain reaction (PCR), a method for detecting the presence of specific sequences of DNA or RNA. The kit contains three different "primer" sets (small pieces of DNA that stick to specific regions of the virus' genome), all three of which need to return positive results to confirm presence of coronavirus. One primer set has already been found to not work in testing. The CDC then announced that two positive results are enough, though some labs stated that a second primer set is also unreliable, and are now making their own kits instead.

Birth and cell death may go hand in hand

Altering the timing of birth changes patterns of cell death in mouse brains

NIH Image Gallery via Flickr

Considering how fragile the brain is, it might sound absurd that when forming one, over half of the neurons that are initially created end up dying during the first years of development. This is usually done through apoptosis, or Programmed Cell Death (PCD), a mechanism in which the cell basically dies from within. Although neuroscientists have known that PCD is essential for normal development for decades now, there is a whole lot we still don’t know about that process. For example, how exactly does the brain know when to start and stop cell death? To start figuring that out, Alexandra Castillo-Ruiz and colleagues at Georgia State University posed the question: does birth trigger cell death?

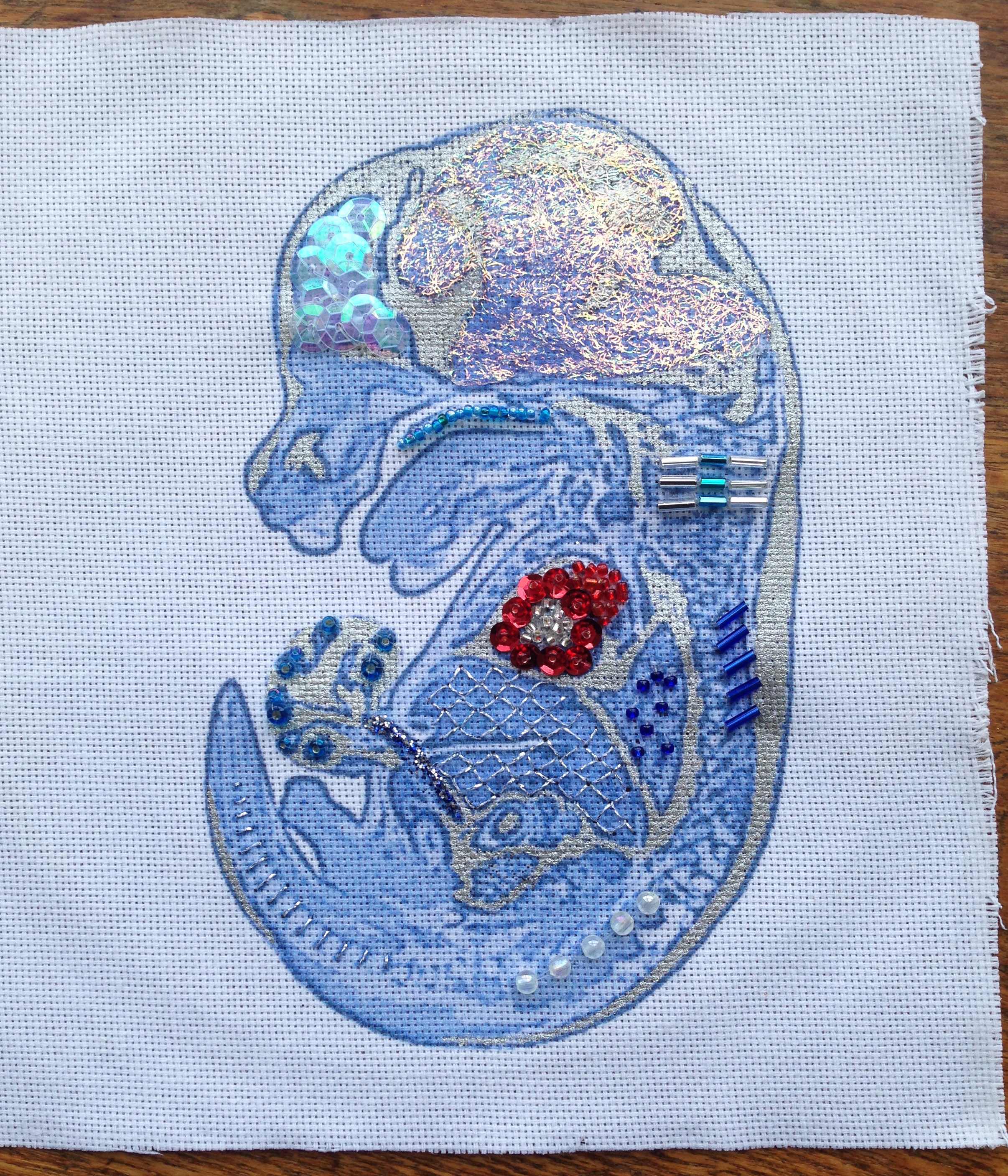

Embroidered image of a mouse embryo.

NIMR London via Flickr.

To answer that, the scientists manipulated the timing of the birth of mice — either advancing or delaying birth by one day — using different combinations of hormones. They then examined the extent of cell death in the mice’s brains. Looking at areas where cell death happens quickly after birth, the team found that advancing birth by one day also advances cell death. Interestingly, while the timing of PCD was advanced, the overall number of dead cells was actually reduced. On the other hand, delaying the birth by one day did not affect the timing of PCD, but did increase the number of dead cells.

This is the first study to link the actual process of birth to changes in cell death in the brain. While it looks only at specific areas of the mouse brain, it is still important, especially considering how often we do advance human birth dates for various reasons.