The secret to sounder sleep may be lurking in our guts

New research shows that stressed med students on probiotics got better shut-eye

It’s 2 am. I’ve been in bed for hours, but I can’t fall asleep. I’m worrying about my upcoming project deadline or whether I’m eating enough protein or that time three months ago a waiter told me to enjoy my meal and I said, “You too!”

I know that I’m not alone in this. Over a third of Americans reported that they experience difficulty sleeping at least once a week, and stress is likely a major factor.

It’s tempting to reach for a pill to help us sleep — about 4 percent of Americans use prescription sleeping aids. But while medication may seem like an easy solution, many worry about addiction or rare but serious side effects like amnesia and hallucinations. So research labs across the globe are looking for better, safer ways to help people get the sleep they need.

Although historically sleep researchers have focused on the brain, new experiments are looking elsewhere: the gut. Recently, studies in both humans and animals have linked gut microbes to sleep behavior. Now, a research group in Japan is asking whether ingesting certain microbes can actually help us sleep better, especially in times of stress.

Results from a recently published study by researchers from Tokushima University and the Yakult Central Institute in Japan seem promising. In the study, microbiologists gave a fermented milk beverage to medical students undergoing a very stressful examination. The drink contained a type of bacteria called Lactobacillus casei strain Shirota (LcS), which has several purported health benefits like improving digestive health and reducing infections.

Lactobacillus is a genus of bacteria, meaning it's a group of bacterial species that are related, but not exactly the same. Many Lactobacillus species naturally occur in the human gut and in fermented dairy products like yogurt. However, different species within a genus can have very different effects on human health.

For comparison, a dog and a wolf belong to the same genus, but you wouldn't want a wolf in your house. Similar differences exist between species of bacteria, which is why many studies, including this one, examine the effects of a single species.

In the weeks before and after the exam, researchers instructed students to drink either a beverage containing the bacteria of interest (LcS), or a placebo beverage. The study was double-blind, meaning neither the researchers nor the students knew which drink was which until after all of the data had been collected. As expected, students’ stress ratings increased as the exam approached. Unsurprisingly, the tense students who drank the placebo beverage took longer to fall asleep. This placebo group also experienced decreases in slow-wave sleep, a type of deep sleep which is thought to be important for memory. Although effects of stress on sleep are not always consistent across studies, increased sleep latency and decreased slow wave sleep have both been previously associated with stress.

But while the group that drank the LcS concoction had similar increases in reported anxiety, they didn’t seem to experience the sleep problems that usually come along with exam stress. They took less time to fall asleep, had more slow wave sleep, and reported being less sleepy when they woke up, compared to the placebo group. The study authors reported no harmful side effects and concluded that “daily consumption of LcS may help to maintain sleep quality during a period of increasing stress.”

Now, this sounds pretty good. But before you run out and buy a case of this probiotic drink, the study did have some caveats. First, researchers studied the effects of this drink in a fairly small and homogenous population: Japanese medical students. Small sample sizes are more subject to bias, and therefore the study's conclusions may not hold true in the general population. This trial only used about 50 participants in each group. In comparison, Phase 3 clinical trials, which most drugs must go through before they are approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), consist of hundreds or even thousands of participants.

Second, it’s always important to look at who’s paying for the research being conducted. In this study, most of the researchers were paid by a company called Yakult Honsha Co.— the same company that makes (and sells) the probiotic beverage being assessed.

Does that mean the study is worthless? Probably not. The double-blind design makes it much less likely that researcher bias will affect the outcome of the study. Nevertheless, it’s important that this study be replicated by another group not affiliated with Yakult.

Finally, this study doesn’t answer how this probiotic beverage affected sleep. Research on probiotics has been plagued by the question of whether microbes we eat can actually survive the highly acidic environment of the stomach and establish a foothold in the intestines long enough to make an impact. After all, our gastrointestinal tract is already teeming with bacteria, all competing for limited resources like space and nutrients. Were the LcS bacteria used in this study actually able to set up shop in the intestines of the participants? If so, what chemicals did they produce once established in the gut? Did they signal to the brain through the vagus nerve, or secrete compounds that alter immune system function? We still need to figure out the mechanisms through which probiotics affect our bodies before we actually understand their impact.

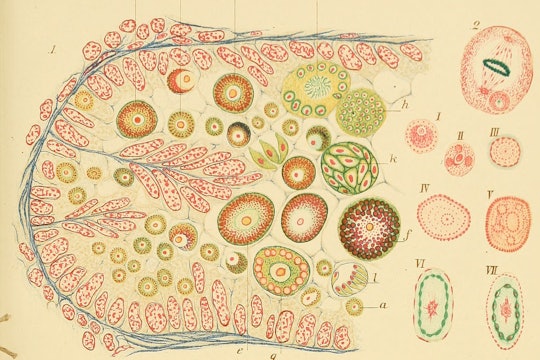

These questions won’t be easy to answer. The microbiome is insanely complicated; it’s an entire ecosystem living in our gut that we are only beginning to understand. Furthermore, this is a world that is highly dynamic, changing based on our diet, our stress levels, the antibiotics we’ve taken, and a host of other factors. Unlike a healthy heart, which likely looks similar between different people, a healthy microbiome might look very different between different individuals.

Still, overall this study on the beneficial effects of LcS bacteria is promising. Studies like this one have given us tantalizing insights into how we might manipulate the microbiome to treat everything from post-partum depression to colorectal cancer. It is a field with the potential to revolutionize medicine — but there’s still an enormous amount of work to be done before we can understand the complex workings of our inner microbial worlds.

The study discussed here sounds well-designed, but I’m glad that Hannah mentioned the need to expand the sampled population. It’s possible, for instance, that this effect occurs in those of Japanese descent but not for others. In addition to the many influences listed above, gut microbiota varies by race.