Lab Notes

Short stories and links shared by the scientists in our community

Rats love hide and seek

Studying play in animals could allow scientists to answer important questions about decision making, social behavior, and even theory of mind.

Anna Marchenkova in Wikimedia Commons

In general, neuroscientists consider anthropomorphizing animal behavior to be a faux pas. But increasing evidence indicates that many human behaviors can be observed in other animals, if only in a rudimentary form. Well-known to many people who keep rats as pets is their ability to play. Recently, researchers in Germany published a study on play behavior in rats, specifically the game hide-and-seek. This game may seem relatively simple, but requires complex behaviors including decision-making and perspective-taking.

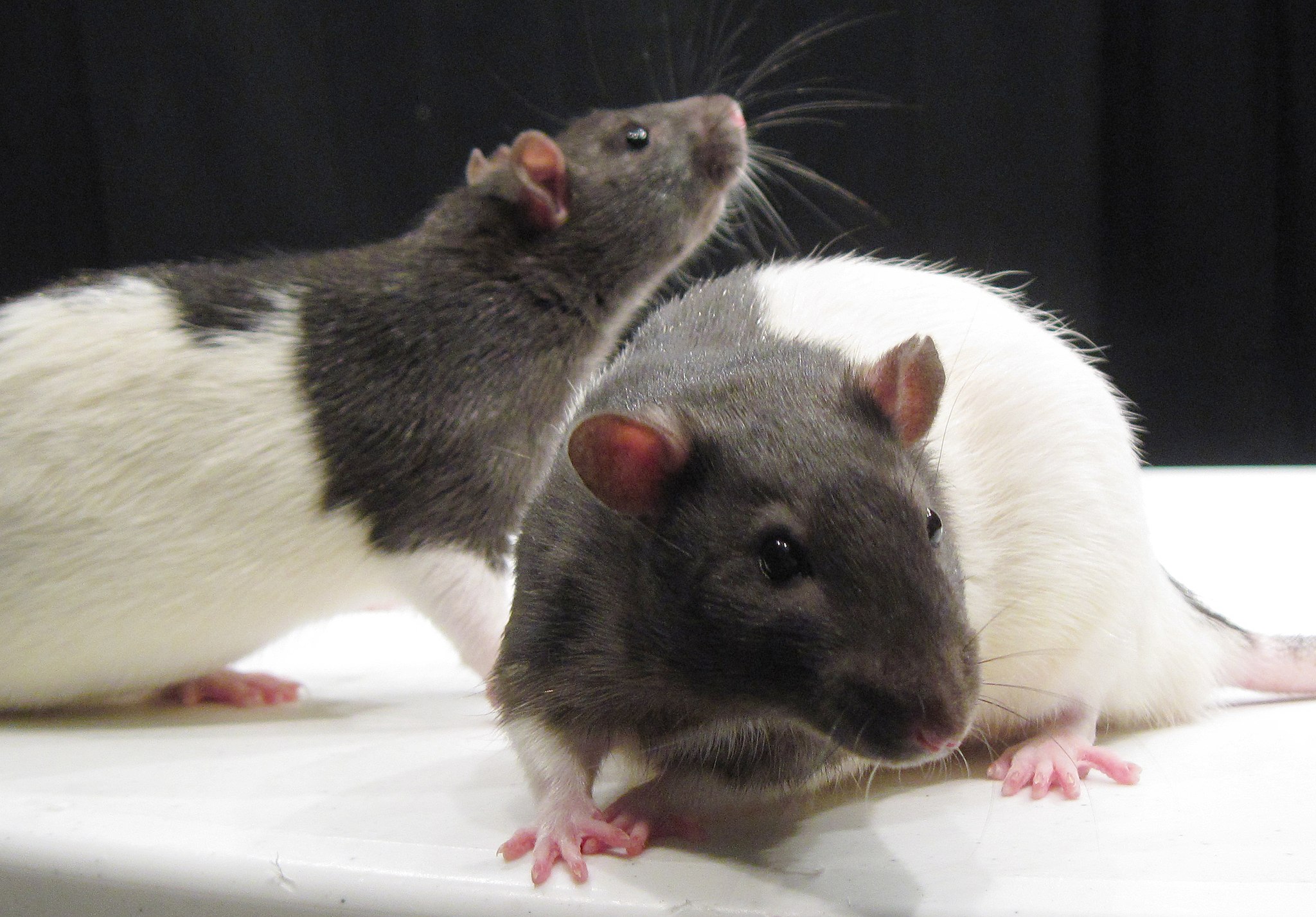

A pair of black and white rats

Jason Snyder on Wikimedia Commons

Fascinatingly, rats were able to learn to be both hiders and seekers. The game began when rats were placed in a box. If the box was open, the rats learned that this meant they were supposed to go and hide. The rats were able to strategize hiding location and showed a preference for an opaque box hiding place rather than a clear box. If the lid was initially closed, the rats learned that this meant they had to go and find the experimenter.

The experimenter would pet and tickle the rat at the end of the trial. In many tasks used in modern neuroscience, food is used as a reward, but in this study, the social interaction and the "fun" of the activity were enough to motivate the rats to learn this complex behavior. Further supporting this, the researcher saw that rats were having “fun” as evidenced by excitement behaviors such as freudensprung (“joy jumps”), and rats re-hiding after being found.

To understand underlying processes of this, electrical signals were recorded from the prefrontal cortex, a brain region involved in learning and social behavior. These recordings showed a subset of cells were activated during play and specifically when the box was closed (the game start cue). Scientists are still trying to figure out the implications of the neural activity that was recorded during these play activities. While we cannot see what the rats were thinking, this study does present important evidence of play behavior in rodents. Hide-and-seek is a complex game that allows for several aspects of the cognition to be studied (decision making, navigation, perspective taking). A task like this has lots of promise to be used to study the basis for animal behavior which could have potential implications in furthering our understanding of human behavior.

Graphene-based films shield human skin from mosquitoes

Scientists have exploited graphene and its derivatives for all kinds of applications — the latest is to ward off the pesky mosquito

James D. Gathany/CDC

Have you ever found yourself irritated by mosquitoes in a hot and humid climate, despite the insect repellent you've repeatedly slathered all over your body? If chemicals don’t work for you, then perhaps graphene-based clothing may help!

Graphene is very unique as far as any material goes. Despite being only atomically thin, it is dense, electrically conductive, and 200 times stronger than steel. Scientists have exploited graphene and its derivatives (such as slightly oxidized graphene) for all kinds of applications; the latest yet is to ward off the pesky mosquito.

Researchers at Brown University exposed skin patches for five minute intervals to ~100 pathogen-free female Aedes aegypti mosquitoes (the bane of dengue fever, yellow fever, and Zika virus) and monitored their activity. The results showed that dry graphene oxide-covered skin never permitted a single mosquito bite, unlike the unprotected skin or cheesecloth-only controls, where bite numbers could range between five to 20. Fewer mosquitoes landed on protected skin, and even if they did, they never dawdled. From these observations, the researchers concluded that the graphene-based films masked the molecular signals mosquitoes needed to sense a live presence. Graphene’s impermeability essentially rendered human victims invisible to mosquitoes.

When the researchers smeared the graphene-protected skin with human sweat or water, mosquito landings were much more frequent. However, this time, if graphene-based films became too wet, they swelled and became porous—and the underlying skin became vulnerable to mosquito bites. Here, only the excellent mechanical strength of reduced graphene-based films (i.e. with reduced oxygen functionality) barred mosquitoes from reaching the skin layer to take a bite, showing that using reduced graphene-based films in wearable technologies can provide mosquito bite protection in both dry and wet conditions.

A mosquito in action.

CDC/ Prof. Frank Hadley Collins from the Public Health Image Library

Perhaps mosquito-bite prevention by graphene-based materials is not a surprising result. These materials have already been used in water filtration, for encapsulation, and to lace plastics and metals as a means to enhance overall mechanical strength. Graphene wearables have also generated much buzz as graphene’s electrical conductivity allows for the design of ‘smart clothes’, whilst its mechanical strength enables the fabric to accommodate stresses generated by body movement.

But to prevent mosquito bites is probably the most creative application yet. An overkill, perhaps? Nevertheless, it would be a tremendous relief to humans cohabiting with mosquitoes—we know how tenacious these pests can be.

Step away from the immunosuppressant drugs — antibodies are on the case!

New research in mice suggests that using, not suppressing, the body's defenses against intruders is a promising avenue for treating autoimmune diseases

Graham Beards on Wikimedia Commons

Autoimmune diseases are disorders where the body’s defense system turns on itself. This group of diseases, which includes rheumatoid arthritis and lupus, represents one of the top 10 causes of death in women. Automimmune diseases are currently primarily treated by immunosuppressive drugs which hold the immune system in check, but this type of therapy comes with the risk of developing severe infections and various other side effects.

Recently, a team of international researchers have found that distracting the body’s immune system by targeting its attention elsewhere could be an effective alternative to long-term immunosuppression with pharmaceuticals. They discovered that injecting antibodies against red blood cells into mice forced their immune systems to re-direct their efforts toward these specific cells, sparing other tissues from attack. They found that this approach was an effective treatment in various models of mouse arthritis, preventing the infiltration of inflammation-causing immune cells into the joints.

Anti-red blood cell antibodies derived from healthy volunteers are in fact already being used to protect the rhesus positive (Rh+, referring to the plus or minus sign after your ABO blood group) babies of Rh- mothers, and such medications could be re-purposed to treat various other autoimmune diseases. This method of treating autoimmune diseases is promising in that it may decrease our reliance on immunosuppressant drugs someday down the line.

Captive sea otters (adorably) raise orphaned pups as their own until they are ready to be released back into the wild

New research from Monterey Bay Aquarium scientists finds that the pups and their own wild babies account for 55% of the growth of a California sea otter population

Peter Burka on Flickr

Rescue and rehabilitation of stranded or injured wild animals is one tool at our disposal to protect endangered or threatened species, and in the U.S. it has helped conserve marine animals like the Hawaiian monk seal and Florida manatees. Zoos and aquariums substantially contribute to these efforts. New research out of the Monterey Bay Aquarium, published in the journal Oryx, highlights just how important — not to mention downright adorable — this work can be.

Sea otters are called "keystone" species, meaning that they are the linchpin that holds their ecosystem's food web together. A long-running line of ecological research has found that when sea otters are present in coastal ecosystems, populations of sea urchins (one of their favorite foods) are kept in check, allowing marine kelp forests to proliferate. This is a balanced, healthy coastal ecosystem. But when sea otters disappear, sea urchin numbers explode, they eat all the kelp, and the coast starts to look pretty bleak.

Sea otter populations are still recovering from the effects of hunting for the fur trade in the 18th and 19th centuries, and their protection remains an important objective for California's Monterey Bay Aquarium. Between 2002 and 2015, a team of aquarium scientists, led by Karl Mayer, rescued 37 stranded and orphaned sea otter pups along the coast. They brought them back to the aquarium and gave them to captive female otters to raise as their own. After the pups were weaned, they were released into the Elkhorn Slough wetland, an estuary that is managed by state and federal natural resource agencies. This in itself was a great success, but Mayer and his team wondered about the fate of these released pups and how much they contributed to their newly adopted wild population — an important mark of how successful the aquarium's rehabilitation and reintroduction project truly is.

They found that released female otters reproduced at the same rate as fully wild otters, an encouraging sign that reintroduction can contribute to a healthy wild sea otter population. In fact, over the lifetime of their study, the reintroduced females and their own wild pups accounted for 55% of the growth of the Elkhorn Slough sea otter population! This is fantastic news for California's sea otters, and shows how captive animals can contribute to conservation of their wild counterparts.

Photo from MaxPixel

You probably didn't need another reason to love sea otters, with their hilarious old-man whiskers and their penchant for hand-holding, but let's add this conservation triumph to the list, anyway.

NIH seeks to enroll one million individuals in genetic counseling to improve health research diversity

Medical research has had a long history of disproportionately benefiting wealthier countries and white people, rather than ethnic minorities

Perry Grone on Unsplash.

The National Institutes of Health’s ambitious All of Us Research Program aims to promote diverse and inclusive health research. In a milestone move, they recently awarded $4.6 million to Color, a health technology company, to establish a nationwide genetic counselling resource in the U.S.

Medical research has had a long history of disproportionately benefiting wealthier countries and white people, rather than ethnic minorities. We see this consequence resulting from clinical trials and massive databases that under-represent racial, ethnic, gender, sexual orientation, socioeconomical and geographical minority groups. Unsurprisingly, this effect is also related to how these underrepresented populations have poorer access to quality health care.

To combat this, the NIH began its All of Us Research Program in 2018 with the goal of enrolling at least 1 million diverse participants in the United States to improve health programs and biomedical research. They planned to collect completed health questionnaires, medical records, physical measurements and more, which researchers could use to improve diagnosis, treatment, and prevention methods for all individuals.

The All of Us Research Program also collected another piece of data from their participants: their DNA. They wanted to sequence the genomes of their 1 million participants. A year later, they’ve reported that out of the more than 175,000 participants so far, 80% of them come from historically underrepresented groups. With this progress, a game-changing move followed.

The company Color will be building a nationwide genetic counseling service to communicate the results back to participants transparently, responsibly and ethically.

Tbel Abuseridze on Unsplash

The program has given the $4.6 million to Color, a California-based health technology company, to sequence and analyze these genomes. Color will use the money to start building a nationwide genetic counseling service to communicate the results back to participants transparently, responsibly and ethically. They anticipate the service to be especially helpful for participants found to be at potential risk for genetic diseases or adverse side effects to clinical drugs.

While I feel elated with this encouraging progress, it’s also long overdue. We should expect healthcare and science to be diverse and inclusive, and we are each accountable for that responsibility as well. I hope this research program will achieve the beneficial impact every individual fully deserves, and that science will serve the communities that it should have been from the start.

Opioid use after surgery is higher in the U.S. & Canada compared to Sweden

A new study investigates whether the culture surrounding pain medication prescription habits in different countries could be contributing to opioid misuse

In 2017, more than 130 people died per day in the US from opioid related drug overdoses. This crisis has triggered a call to hold drug companies responsible for putting Americans at risk. In August 2019, a landmark ruling in Oklahoma fined Johnson & Johnson $572 million for their ‘public nuisance’ marketing strategies, and it remains to be seen whether this decision will set a precedent towards more drug companies being held accountable in the future.

But even if we hold drug companies responsible for the opioid crisis, how will the country move forward from here towards recovery?

To help answer this question, a recent study investigated whether the culture surrounding pain medication prescription habits in different countries could be contributing to opioid misuse.

Researchers asked the question: after surgery, do the rates of opioid prescriptions dispensed vary between the United States, Canada and Sweden?

Tbel Abuseridze on Unsplash

The researchers compared patients undergoing low-risk surgeries in the US and Canada (the two countries with the highest per capita consumption of opioids) with patients in Sweden, and found that patients in the US (76.2%) and Canada (78.65) were seven times more likely to fill opioid prescriptions after surgery compared to Swedish patients (11.1%). And of these prescriptions, 45% of prescriptions in the US surpassed a threshold equivalent to 200 mg of morphine compared to just 5.4% in Sweden.

The large dataset allowed researchers to compare demographically similar patients and conclude that systemic factors, such as prescribing habits, public attitudes towards pain medication, and the drug marketing and regulatory processes, were likely impacting US prescription numbers more than individual patient needs.

These numbers highlight a stark difference in the drug culture of the US compared to Sweden. Although the data in this study cannot represent the number of pills that patients consumed, a 2018 study found that the US patients consume between 5-59% of their prescribed opioids, and an overwhelming 70 percent of people kept these unused pills. With 11.4 million Americans misusing prescription opioids per year, it stands to reason that America’s recovery from the opioid epidemic may require systemically altering how drugs are prescribed.

Some changes have already begun: in 2016, Massachusetts was the first state to implement a seven-day limit on opioid prescriptions to reduce the amount of unused drugs available in homes, a practice that many US states have implemented since then. Additionally, studies investigating how to manage pain through short-term opioid prescriptions or non-opioid pain medications, like acetaminophen and ibuprofen, will be of great value moving forward. While solving the opioid crisis will take time, quantifying the pain management needs of patients and organizing the vast data sets of prescription information can help us formulate solutions.

The unique chemistry of cats' guts make them the perfect host for Toxoplasma gondii

This information might allow Toxoplasma researchers to switch from lab cats to lab rats

Toxoplasma gondii is a common parasite that causes an infection called toxoplasmosis in approximately one-third of humans, so research in this area is important to human health. T. gondii's lifecycle is curiously complex, and it has gained infamy for it's tendency to reproduce in the intestines of cats. The reason for this exceptional specificity has previously been unknown. Now, a study published in PLOS Biology in August has identified the exact molecular components in the feline intestine that create the conditions necessary for the parasite to reproduce.

The research found that a chemical called linoleic acid is necessary for the sexual lifecycle of T. gondii. An enzyme in the intestines of most mammals called delta-6-desaturase usually helps convert linoleic acid to arachidonic acid. But cats are the only mammal known to lack this enzyme in their guts – therefore, their guts maintain high enough levels of linoleic acid to allow for the parasite to reach sexual maturation. After the researchers figured this out, they found a way to stop the activity of delta-6-desaturase in mice, which means that in the future they may be able to stop using cats – a point of contention with animal rights activitists – in the lab. Eventually they may even be able to grow T. gondii in cell culture to learn more about this common (and, some say, mind-controlling) parasite.

How humans have shaped the brains of our furry friends

By breeding dogs for specific behaviors, humans have also altered the physical structure of their brains

Dog-watching at the park on a Sunday morning makes us appreciate the diversity across different breeds. From tiny Yorkshire Terriers to giant Great Danes, each breed has its own unique characteristics. Although dogs may be bred for specific physical traits like size or coat length, they can also be bred for specific behaviors like hunting or herding. Researchers wanted to know if these behavioral specializations were associated with differences in brain structure.

Photo by Matt Nelson on Unsplash

A new study published in the Journal of Neuroscience and led by researchers at Harvard University looked at the brains of 62 purebred dogs from 33 different breeds to answer this question. Using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), they found that there were significant differences in brain anatomy between different breeds. Furthermore, these differences could not be fully explained by variation in brain size or skull shape.

Researchers looked at brain anatomy in six different networks, each associated with different potential functions like drive and reward or social action and interaction. Fascinatingly, these networks correlated with specialized behaviors seen in different breeds. For example, sight hunting, a behavior for which Greyhounds are bred, was associated with brain areas related to eye movement and spatial navigation. Moreover, they found that brain variability between breeds had arisen fairly recently (in an evolutionary sense), indicating that selective breeding by humans is most likely responsible for molding the brains of different dog breeds. The authors state that dogs represent a great “natural experiment” that could become a good model to study brain variation and its relationship with function in light of evolutionary pressures.

The rise of a mysterious lung illness begins to expose the dangers of vaping

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control have reported at least 450 cases in 33 U.S. states, as policy makers call for action

Photo by Sharon McCutcheon on Unsplash

Walking through a park, across a street, or heading to work, all of us have suddenly caught the scent of fruit, chocolate, peppermint, or some other flavor coming from someone vaping nearby. As vaping has rapidly gained popularity since it’s invention in 2003, little has been said or written about its potentially dangerous health impacts. Many shops and restaurants in the U.S. and Canada have banned vaping on patios, near doors of establishments, and other public areas where smoking cigarettes is not permitted. Now, vapes have made the news in a negative light for the second time.

As CBC reported on August 23, 2019, an Illinois resident passed away following severe respiratory illness likely brought on by vaping, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control. Currently, the CDC is investigating at least 450 cases of severe respiratory illness across 33 states, all thought to be related to chronic vape use. The cause is yet unknown, and Canada's chief public health officer, Dr. Theresa Tam, reported to the media that the mysterious illness has not yet reached Canada. Tam also cautioned that everyone should be aware that the long-term effects of vaping, given that the number of chemical ingredients in vape oils, are unknown.

We may not know the exact link between vaping and this lung disease, but we do know some things about the dangers of vaping. Vaping entails inhaling steam and other chemicals, like formaldehyde, into the lungs. Human lungs are coated with mucus inside that protects lung cells by catching particulates before they infiltrate the rest of the body. Exposure to these particles thickens the mucus layer inside the lungs, decreasing the lungs' ability to fight off respiratory infections. Inhaling steam also prevents the lungs from absorbing as much oxygen as they should. Lower oxygen levels in the body decreases the health and functioning of major organs and muscles. In addition to these, the negative effects of ingredients in vape oil remain unknown and/or unreported.

These health risks of inhaling a foreign substance of any kind into your lungs point to potential dangers of long-term vaping use. While the cause of death and illness in individuals who vape isn't exactly clear yet, one thing is certain: Health officials and policy makers — and even Donald Trump — are beginning to worry about the correlation between the illnesses and increased vape use. We are probably just seeing the beginning of vaping-related diseases and deaths.

Shapeshifting hydrogels with CRISPR inside rearrange on command and interface with our bodies

Programmable CRISPR-responsive smart materials, like DNA hydrogels, are much more likely to become game-changers in our lifetimes

All eyes are on CRISPR, the gene-editing sensation touted to solve a slew of long-standing medical challenges, such as engineering CRISPR nanoparticles as a potential therapeutic for Alzheimer’s disease or working towards an antidote to box jellyfish stings. Now, a new study explores new territory where CRISPR has the potential to make its mark: smart biomaterials.

Smart biomaterials are biologically responsive materials engineered to respond to internal and external cues, such as changes in light, temperature, pH or enzyme activity. Now, bioengineers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology have taken smart biomaterials one step further by harnessing CRISPR’s unique DNA modifying properties to create DNA-hydrogels that change shape on command. These hydrogel polymers have web-like structures that are held together by DNA strands. Together with the programmable enzyme Cas12a, CRISPR precisely targets DNA bridges and cleaves them, triggering a shift in the polymer’s shape or consistency.

These programmable CRISPR-responsive smart materials can be used to interface with various biological signals or enhance current biomaterial approaches, such as in the fields of tissue engineering and molecular diagnostics. In this particular study, the researchers engineered different DNA-based materials to explore different applications, such as using CRISPR-based DNA hydrogels to release enzymes, nanoparticles and live cells, and even modulating the hydrogel's electrical properties for sensing and diagnostics.

CRISPR-controlled hydrogel technology is poised to revolutionize bioelectronics.

Photo by Allie Smith on Unsplash.

In fact, CRISPR-controlled hydrogel technology is poised to revolutionize bioelectronics — electric circuitry that interfaces with biological systems, which may see medical devices to sense and destroy dangerous pathogens become a reality.

Transitioning any innovation to a clinical setting involves plenty of time, investment dollars and regulatory red tape. Compared to the safety risks involved in directly treating patients with CRISPR, CRISPR-based DNA hydrogels are much more likely to become game-changers in our lifetimes.

Meet the all-star cast of marine bacteria that can ruin your warm-weather activities

Each member of the Vibrio family is unique, but they're all likely getting more common as the oceans warm

Photo by Sven Scheuermeier on Unsplash

It’s official. This summer was one of the hottest on record, and July was the warmest month ever recorded on the planet. The sweltering summer was a boon for bacteria from the Vibrio genus. Several reports of flesh-eating bacteria, Vibrio vulnificus, are dotting America’s coastline with casualties. Sea temperatures are high, rising, and stretching these bugs to new beaches — a new normal in this climate crisis. But if more abundant flesh-eating bacteria weren’t daunting enough, entirely different species of Vibrio infections are also predicted to rise.

So, meet the all-star cast of marine bacteria that can ruin your warm-weather activities and tropical vacations:

Vibrio vulnificus: This “flesh-eating” bad boy causes lethal infections in wounds, as well as shellfish poisoning. Does necrotizing fasciitis sound appetizing?

Vibrio anguillarum: Likely voted “Most Likely to Decimate Shellfish Supplies” in high school (if bacteria went to high school, that is), this bacterium threatens aquaculture of crustaceans and fish.

Vibrio cholerae: Cholera. Yes, that cholera. Millions of people infected annually, lethal in hours if untreated.

Vibrio alginolyticus: This angsty germ seems to thrive on being a nuisance. It produces the famous neurotoxin in pufferfish and also causes swimmer’s ear.

Because each of these Vibrio species (and others) thrive in warm waters, they are all expected to get a boost from climate change. With all the bacterial diversity in the world, it’s hard to believe that this little-discussed group could be such a problem. But warming ocean temperatures may well put Vibrio on course to being a household name.

Happy swimming and seafood-eating!

Unhatched turtle embryos can shape their own sexual destinies

By moving to cooler areas inside the egg, turtle embryos can influence their own sex, and maybe ward off climate change too

A turtle develops into a male or female depending on temperature – females hatch from warm eggs and males hatch out of cool eggs. Turtle nests naturally fluctuate in temperature, and this variation leads to clutches producing a mix of male and female hatchlings.

But a new study in Current Biology suggests there’s more to it than that: instead, embryos can guide their own sex determination by moving between warmer and cooler parts of the egg.

One end of a turtle egg can be as much as 4.5 °C (40.1 °F) warmer than the other end, meaning that embryos experience very different temperatures depending on where they are in the egg. Intrigued, the researchers then tested whether embryos could sense and respond to these temperature differences. Could unhatched turtles perhaps influence their own development?

To do this, the team treated the eggs with capsazepine, a drug that shuts down key ion channels involved in temperature sensing, and recorded how embryos responded to a heat source on one end of the egg. Drugged embryos didn’t move towards the heat as much as control animals, and were far more likely to develop into males.

Turtle embryos have the raw tools – a big thermal gradient and the ability to sense and respond to warmth – to influence their own development.

Global climate change threatens turtles and other animals that rely on temperate-dependent sex determination by disrupting sex ratios. We’ve already seen examples of this in the wild – a few years ago, scientists were dismayed to find 99% of green sea turtles sampled at key breeding sites in Australia were female, crippling their ability to reproduce.

Global climate change threatens turtle survival by disrupting sex ratios.

The razor-thin margins between “all male” and “all female” nests combined with the frantic pace of global warming means that some populations are already on the precipice of ecological disaster. While being able to shimmy a couple of inches in an embryo isn’t going to stop catastrophic changes in sex ratios, it may allow turtles to buffer the short term effects of climate change.

Ant activity has outsize impacts on soil moisture and plant growth

Consortium member Madison Sankovitz explains her newly published research study

Photo by Matheus Queiroz on Unsplash

Although ants are well-known as being household pests, most of our terrestrial landscapes would likely be drastically different without them. Ants provide an essential ecosystem service by maintaining soil. They aerate soil by digging tunnels for their nests (which also allows water to reach plant roots), and they mix nutrients through soil.

Ants’ nest-building and foraging behaviors help soil remain fertile for plants and microorganisms to thrive. In fact, many plants would not even be able to grow where they do if ant nests didn’t exist. In a newly published study, I and two of my colleagues at the University of Boulder - Colorado have shown that factors like proximity to an ant nest and whether the nest is on a slope substantially influence the soil moisture and plants that live in the area.

We investigated patterns in the soil properties and plant communities surrounding 24 nests of the montane ant, Formica podzolica. After counting plant specimens and studying plants and soil in the lab, we found that soil moisture increases with distance from nests and that plant abundance decreases with distance from nests. We also found that the soil downhill from nests harbors more plants than soil uphill from nests, which we conclude means that nutrients and water from nests flow downhill to fertilize soil. This ant species occupies a huge geographic range from Alaska down to New Mexico, so we think they play a key role in shaping plant communities throughout much of the western U.S. and Canada.

Our study adds to a body of literature about ants as "soil ecosystem engineers." Without ants, subalpine habitats like the one in this study could be extremely different. We and other scientists continue to study how ant activity affects the soil, including the possibility of harnessing their services in both ecosystem restoration and agricultural crop production.

Scientists tried to make knives out of frozen human poop

They wondered: is it possible to cut animal hides with a human feces blade?

Michelle R. Bebber & Metin I. Eren.

Have you ever wondered if knives manufactured from frozen human feces could function as well as regular knives? While the thought has never crossed my mind, researchers at Kent State University and the Cleveland Museum of Natural History wondered about this very question, and sought to find the answer.

And yes, there's a good reason why.

In Shadows in the Sun: Travels to Landscapes of Spirit and Desire, Colombian-Canadian anthropologist Wade Davis recounted an ethnographic account (below) of an Inuit man who manufactured a knife, using his own frozen feces, to butcher a dog:

“There is a well known account of an old Inuit man who refused to move into a settlement. Over the objections of his family, he made plans to stay on the ice. To stop him, they took away all of his tools. So in the midst of a winter gale, he stepped out of their igloo, defecated, and honed the feces into a frozen blade, which he sharpened with a spray of saliva. With the knife he killed a dog. Using its rib cage as a sled and its hide to harness another dog, he disappeared into the darkness.” - Wade Davis

Despite this story being shared across multiple documentaries, books, and academic literature, the credibility of this story remains uncertain. Can such a knife actually cut through hide, muscle and tendons?

To test this claim, the researchers collected human feces to make such a knife. First, researcher Metin I. Eren went on a diet high in protein and fatty acids — consistent with an Arctic diet — for eight days. This diet included chicken thighs, beef fillets, turkey sausages, and salmon. From day four onward, Eren's fecal material was collected and frozen at -20°C. Frozen fecal samples were then either molded by hand or through ceramic molds to create knives. After burying each knife in -50°C dry ice for a few minutes, researchers attempted to slice through pig hide, muscle and tendons to test knife functionality.

An example of a “hand-shaped” knife blade.

Michelle R. Bebber & Metin I. Eren.

Unsurprisingly, the knives manufactured from frozen human feces could not cut through the pig hide — let alone tendons or muscle. Instead, the edge of the knife would melt upon contact with the hide, and leave behind fecal streaks. Even knives shaped from feces from a typical Western diet failed to cut through pig hide.

A knife made from frozen human feces fails to cut through a pig hide, melting and leaving streaks instead.

Michelle R. Bebber & Metin I. Eren.

To be clear, tools manufactured from human feces do exist. For example, you can be innovative when it comes to waste management in space missions, and use solid human waste to produce polyhydroxybutyrate and then 3D print items for astronauts.

While there are countless tales reporting the innovative and resourceful nature of Indigenous and prehistoric people, this particular claim is unlikely to be true. The researchers do suggest exploring the role of different diets or even licking the frozen fecal knife (as reported in the original tale) to further test this claim, but regardless, they remain confident that they gave their knives the best possible chance to succeed and the knives still couldn’t function.

So no, knives manufactured from frozen human feces do not work.

Just in case you were planning to try that out one day.

People across Southeast Asia are breathing in toxic particles because of large fires

New research estimates that carbon particles released from large scale Indonesian fires cause around 36,000 deaths per year

Photo by Joshua Newton on Unsplash

Smoke and ash from a camp fire might smell good, but the fire is actually releasing organic carbon and black carbon particles into the air around you. When fires occur on a larger scale, like they do in Indonesia, these particles can have unintended health impacts.

Fine particles that are 30 times smaller than a human hair, called PM2.5, can get down deep into people's lungs, and can even enter the bloodstream. Once there, PM2.5 particles irritate the lungs and heart, which can be fatal, especially for young kids or anyone with existing health conditions.

New research estimates that, assuming the current rates of fires, logging, and deforestation continue, exposure to air pollution from Indonesian fires could cause around 36,000 deaths per year. Because the particles are airborne, they aren't constrained to Indonesia — particles from fires across the islands that make up Indonesia impact health in neighboring countries such as Malaysia and Singapore, too.

A forest fire seen at Bintan Island, Indonesia.

Photo by Thomas Ehling on Unsplash

There is some potential good news, though: there are several land management strategies that could reduce deaths from fire emissions, some as much as 60 percent.

Researchers developed a simulation tool that allows anyone to test out the effects management strategies, like blocking fires over peatland or in industrial logging sites. The tool clearly and quantitatively highlights the value of conservation efforts and reducing fires, showing that these efforts wouldn't just save trees, they could actually save thousands of lives.

We have many tools in the fight against antibiotic resistance, and we should consider not using them

New studies hold promise for treating tuberculosis — but also suggest that sometimes the best course of action in treating infections is no action

Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb), the bacterium responsible for causing tuberculosis (TB), is a particularly potent pathogen when it comes to antibiotic resistance. Mismanagement of multi-drug resistant strains has resulted in extensively drug resistant TB, which constitutes ~8.5% of multi-drug resistant TB cases. But the drug regimen to treat extensively drug-resistant TB cause substantial side-effects and are very expensive. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration recently approved new drugs to tackle this form of TB which, as pointed out here, could potentially bridge the gap between patients and affordable therapeutics.

Although a welcome development, this move took several years to come to fruition and patients can rarely afford to wait this long. A recent study by a group of Harvard Medical school-associated researchers took a new approach to this problem. They used a fast-screening method on a library about 3000 bioactive molecules to test which ones were effective in fighting Mtb. They eventually narrowed the list down to about 40 candidate molecules. The beauty of the method is that it allows molecules to be tested against multiple variations of Mtb, each with slightly different genetic makeups. The 40 candidate molecules they ended up with are much more likely to be effective in a wide variety of patients, who all likely have slightly different variants of the bacteria than those tested in the lab.

We can, of course, try and churn out new drugs to keep pace with evolution, but the alternate approach of restraint also warrants some consideration. A study published in August found that antibiotic-resistant E. coli grown in antibiotic-free conditions lose their resistance after about 500 generations. Acquiring resistance sometimes comes at the cost of reduced fitness (survival and reproduction) of the pathogen, implying a tug-of-war between these two characteristics.

Such findings come in the wake of calls for heavy restrictions on antibiotic use, which on occasion actually have led to loss of resistance in clinical populations. While completely halting our use of antibiotics is not the most practical course of action, it is definitely one worth thinking about.

Just like your dog, some wolf puppies can play fetch too

This finding might provide clues into how dogs evolved into such good boys

Photo by Robson Hatsukami Morgan on Unsplash

“Stop trying to make fetch happen” is probably what everyone said to researchers in Stockholm, who recently released a preprint describing a surprising feat: three wolf puppies spontaneously retrieving a thrown ball. Previously, play between species that is based on social-communicative cues — like when a human throws a ball and says “Fetch!” — was thought to be unique to dogs, but the 8-week-old pups, named Sting, Lemmy and Elvis, showed otherwise.

In this study, researchers brought in a “puppy assessor” to measure 13 wolf pups against the metrics used to describe the behaviors of dog puppies. During one of the test situations, the assessor, whom the wolves had never met, threw a tennis ball across a room, called the name of the wolf pup and encouraged it to bring the ball back. Over a course of three trials, Lemmy and Elvis responded to the assessor’s call and retrieved the ball twice, and Sting responded to the call and brought back the ball all three times. The other 10 wolf pups either played with the ball on their own or showed no interest in it.

Previously, play between species based cues — like when a human throws a ball and says “Fetch!” — was thought to be unique to dogs.

Photo by Tadeusz Lakota on Unsplash

Other than being what I imagine was an incredibly cute situation, this research fills in an important gap in our knowledge about how wolves evolved into dogs. Most scientists support the theory of self-domestication, in which the friendliest members of a species gain an evolutionary advantage (such as greater access to food or protection). Descendants of these super-friendly wolves eventually gained the traits we associate with pooches, like puppy-dog eyes and floppy ears. But for this kind of selection to take place, there would need to be pre-existing variation in wolf populations that made some pups friendlier than others.

Though all dogs are good boys, Sting, Lemmy and Elvis might be examples of these intrinsically better (wolf) boys.

Updated: January 16th, 2020

The research has now been published in the peer-reviewed journal iScience. Perhaps more importantly, we have videos of the wolf puppies playing fetch.

Here's Sting fully retrieving the ball! There are also videos of wolves playing with the ball but not retrieving it, a noticeably different response.

And for good measure, here is a photo of wolf pup Flea looking adorable after failing the fetch test:

Credit: Christina Hansen

While other parts of the world burn, climate change is triggering floods and disease outbreaks in East Africa

At least 62 people have died and 15,000 contracted chikungunya in Sudan and Ethiopia

Nafeer Sudan on Flickr

As summer ends, an abnormally intense rainy season has flooded several East African countries, including Ethiopia and Sudan. The devastating floods have killed 62 people in Sudan alone. And even after the rains end, health risks persist. Drenched land and ravaged infrastructure summons mosquitoes and disease.

In the aftermath of the flooding, Ethipoian officials have reported over 15,000 cases of chikungunya, a debilitating mosquito-transmitted virus that is similar to dengue fever. The outbreak is being managed by local ministries of health, but there is no vaccine or treatment for chikungunya at this time.

Experts have made clear the link between climate change and sub-Saharan summer floods. Climate change is bringing more intense El Niño events. In the summer, this causes significantly higher sea temperatures near East Africa, leading to more rain and floods. Practically the same sequence of events — flooding and a chikungunya outbreak — occurred last year in Sudan.

It is also worth noting that, with warmer temperatures and more intense hurricanes, the Americas are not immune to this problem. Chikungunya recently became a concern in the U.S., with two locally-acquired cases in Puerto Rico.

Here at Massive, we have reported extensively on the public health threats of climate change. This outbreak is just the latest example of a new normal.

"You are when you eat" may be just as true as "you are what you eat"

Time-restricted feeding keeps mice healthy, even when their circadian rhythms are disrupted

Photo by Clem Onojeghuo on Unsplash

Our bodies contain clocks that regulate everything from our sleep to weight. These clocks consist of a set of genes that underlie the “timing” of the clock. They also control our metabolism, or the process by which our bodies convert food into energy. Metabolic disorders are serious illnesses that can take many forms. Thus, understanding how they work and developing interventions are of the utmost importance.

Lots of metabolic research is done with mice. When mice are provided free access to unhealthy food, they develop metabolic issues. Researchers have observed that these mice also show disrupted cycling of their core clock genes. But when the same mice are given access to the unhealthy food during only a subset of the day, many of the negative metabolic and clock gene consequences are ameliorated. This led to the hypothesis that clock gene cycles could be a primary mediator of a healthy metabolism. This is really important for people who do shift work, or those who are exposed to particularly high light levels at night, both of which disrupt normal human circadian rhythms. The video below explains more background information on this idea.

Researchers at the Salk Institute recently published their investigation of how to prevent obesity in mice with dysfunctional clocks. Mice in their experiment were given an unhealthy diet, with food available either throughout the day or just in a nine-to-ten-hour-long window. The overall caloric intakes of the two groups of mice were kept the same. The researchers then measured several markers of metabolism function. They found that the restricted feeding time kept mice metabolically healthy and lean, even when they lacked a regular circadian rhythm. So, rather than regulating metabolism the clock's main function may be to control the behavioral rhythms of feeding and fasting.

This is exciting in that it lays the foundation for human studies regarding how timed eating can override the consequences of clock disturbances. Regardless, at this point I don’t think it would hurt to put down that midnight scoop of ice cream (or at least have it earlier in the day!)

Take CRISPR/Cas9 outside, use it like a hand-held search engine for wild genomes

Instead of little robots, using proteins as naturally occurring nanotechnology

Bobbie Johnson via Flickr.

It's easy to see CRISPR/Cas9, the revolutionary gene editing tool, as a breakthrough meant only for scientists. It obviously has real world applications, but it'll take time for it to trickle down from academic labs to the world at large.

But perhaps, quicker now. Two nanotechnology companies, Cardea Bio and Nanosens Innovations, are merging and in the process, announced the production of what they call the "Genome Sensor." Cardea CTO Brett Goldsmith described it as a kind of "tricorder." It's a hand-held device that anyone who needs to detect a specific sequence of DNA can use. Cas9, the protein that is used by synthetic biologists to cut DNA at specific sequences, is fixed to a graphene net. Instead of cutting DNA though, it's instead given a sequence of DNA to search a sample of genomes that washes over the net. Since it's hand-held, it can be done live in the field. Or in a field, as the case may be. Imagine a farmer seeing an infection on their land. Instead of removing the infected crops or spraying non-specific pesticides willy-nilly and hoping for the best, the farmer can load a sample on to their hand-held device and get an ID right then there. From there, a specific action can be taken. Says Goldsmith:

The Genome Sensor

Cardea Bio

"We all know what nanotechnology is supposed to be. It's supposed to be these little robots running around, self-replicating, doing cool things, controlled by computers and software, and with wireless communication and things like that. You know, we read science fiction books. The reality of what nanotechnology is, and will be, is: we have little robots, they're proteins themselves. They're made by biology, and we can integrate them with electronics, and we can control them with electronics. And so that's what Cas9 is, it's a biological robot that searches through DNA more effectively than we can do with software alone."

Academic scientists in the field were optimistic but not necessarily sold. Plant and synthetic biologist Devang Mehta, who is not affiliated with either Cardea or Nanosens, after reading about the Genome Sensor, said, "I'm not sure how realistic this is in the near future though as it would require...a significant amount of testing against pathogens and related non-pathogenic species to prevent false positive results — something that isn't talked about in this release. In my view, it's a promising invention that isn't quite there yet in terms of field use."

Start-up releases the world's first GMO probiotic

The company claims the probiotic supplement can cure hangovers, but evidence in humans is lacking

August 2019 saw the launch of the world’s first genetically modified probiotic food supplement. The San Francisco-based biotech start-up ZBiotics is selling 15 ml vials of engineered bacteria - a shot of liquid tech designed to prevent hangover. The vials ($36 for a 3 pack) contain cells of Bacillus subtilis engineered to produce an enzyme called acetaldehyde dehydrogenase. Acetaldehyde is an intermediate in alcohol metabolism in humans and it is toxic. There is some debate as to whether acetaldehyde really contributes to hangover headaches, but it does play a big part in the alcohol flushing response (when the face, neck, and chest become warm and red after drinking alcohol)

Avoid future hangovers! (Maybe)

Photo by Quentin Dr on Unsplash

The engineered bacteria are really good at breaking down acetaldehyde in the lab – but there is no published evidence yet that this does any good in humans. So how is ZBiotics able to sell their product already? Marketing the cultures as a food supplement rather than as a drug allowed the company – founded in 2016 – to move very fast and begin commercial sales before proving efficacy in humans. They are conducting safety trials in animals and hope to conduct human trials in the near future.

The company hopes that they will next be able to develop similar products to help those suffering from lactose intolerance , but this first product is aimed at people who wish to maintain a healthy lifestyle but still over-indulge a little on the weekends. Hangover prevention may seem a frivolous choice for the world’s first GMO probiotic, but it could do a lot of good for the public perception of genetic modification. Keeping the focus on consumer benefit, instead of corporate profit as in many crops engineered to be pest- or herbicide-resistant, may result in people being more willing to engage with GMOs as part of their lifestyle. As co-founder Zack Abbott has said, “Take this product today, and if you feel better tomorrow, then you’ve had a positive experience with genetic engineering.”

Peer review is a rigorous process, but it should leave trainees feeling valued and not bullied

Consortium member Kelsey Lucas shares her story and highlights why this is so important

Tim Gouw on Unsplash

My ultimate low at as a grad student hit like a ton of bricks. Already reeling from a poor advising relationship and sexism from being a female student working in fluid dynamics, my second dissertation chapter was rejected from a journal. But, it wasn’t the rejection itself that stung and in part led me to choose a new field for my postdoc – it was the personal insults flung at me by both reviewer and editor.

Linda Beaumont’s recent call in Nature for anti-bullying policies for reviewers was born out of frustration at a similar student experience. She suggests stronger codes of conduct, like those we’re seeing for scientific conferences, and to make these codes of conduct more visible, like the prominent placement of “Ethical Responsibilities for Reviewers” material on the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences journal website.

As trainees, grad students and early career scientists are just that – trainees. We’re learning, and the kind of response we need from reviewers and journal editors is one of support. Constructive criticism, the kind that helps us see where and how we can grow, is invaluable. The belittling of trainees doesn’t help us; it just pushes us out the door.

"The Nemo Effect" doesn't exist: Pixar movies increased clownfish googling, not clownfish purchasing

People were more interested in fish after it came out, but not more likely to set up an exotic aquarium

H. Krisp on Wikimedia Commons

You might have heard of the ‘Nemo effect’, which described the increase in sales of clownfish (Amphiprion percula) after the release of the movie ‘Finding Nemo’. Although many news outlets reported on this phenomenon back in 2016, there is actually little evidence that it was real.

One 2017 study did show that there was no increase in sales of clownfish after the movie came out, but it was based on limited data. That is why a recent follow-up study by zoologists at the University of Oxford, U.K., looked at the impact of the sequel ‘Finding Dory’ not just on the sale of blue tangs (Paracanthurus hepatus) like Dory herself, but also the public’s general interest in the fish. Because blue tangs can't be bred in captivity, the researchers were safe to assume all the extra fish that would be sold would have to be fished out of their natural habitat. Luckily, the researchers found no increase in sales of the fish. This puts the idea of the 'Nemo effect' to rest.

They did find evidence that more people looked up information about blue tangs in the first two months after the movie was released, suggesting that the movie had a positive effect on conservation awareness. Movies containing wildlife do have an effect on society, it just might not have been what we always thought — and for tropical fish, that's a good thing.

Four things you need to know about hurricanes, according to Massive

Climate change, mental illness, and disease outbreaks

Long after the storm surge has receded, the winds have died down, and the clean-up has begun, hurricanes leave a lasting impact on affected communities. We at Massive have put together a curated list of our past stories about these powerful and frightening storms.

- Mosquitoes thrive in flooded, stagnant water, and hurricanes can kickstart disease outbreaks.

- In places with aging and insufficient infrastructure, water quality literally goes down the toilet after a big storm.

- In addition to their human toll and property damage, hurricanes and other natural disasters leave lasting impacts on the mental health of survivors.

- And as if a handful hurricanes per year wasn’t bad enough, the ongoing climate crisis is making them (and many other disasters) stronger and more frequent.

Your anonymized data might not be as anonymous as you thought

A new study raises serious ethical and practical questions about data security

Photo by Olesya Yemets on Unsplash

What happens to the data you provide when you visit your doctor's office, fill out any kind of health-related form, or participate in a clinical trial? There are many ways that personal data are protected to ensure your privacy. These protections are governed by different levels of regulation, but sometimes become exempt from regulations governing human subject research.

A recently published study described a statistical model capable of re-identifying individuals from de-identified (anonymized) data, even from a heavily incomplete dataset. The researchers report that “99.98% of Americans would be correctly re-identified in any dataset using 15 demographic attributes,” with a low average false-discovery (mis-identification) rate, proving that it is very possible for bad actors to attribute specific data to individuals.

Anonymized data sets are collected, shared and used daily at scale by health care organizations for research purposes. This paper is both shocking and controversial: Was it ethical for the researchers to share this model? Does it make it easier for hackers to get our private health information? One thing is clear: Data security, although an unexciting topic, is a critical area of technology that needs our attention.