The psychedelic renaissance is here. Will it last this time?

To avoid the mistakes of the past, scientists and society need to open their minds

Astounding preliminary research suggests psychedelics may yet revolutionize mental health care. But the researchers involved must be careful in all their conclusions and promotions, 50 years ago, one of them had the whole field shut down.

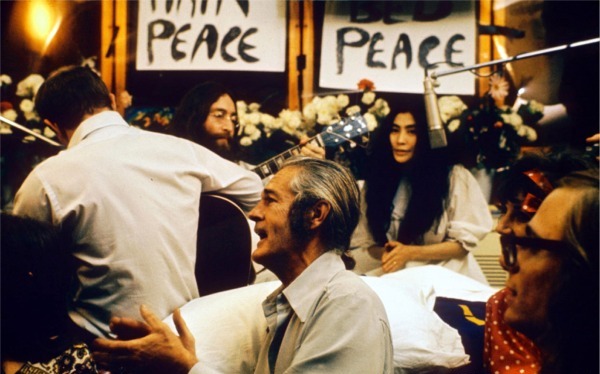

In only half a century, psychedelics have embodied the highest highs and the lowest lows of the American consciousness – from a revolution in therapy to a reputation for drug-addled lunacy. Unwittingly, when Harvard psychologist Timothy Leary signaled springtime for the "Summer of Love," promoting LSD as a means to achieve cosmic connection, he also drew closed the curtain on academic research into a class of substances which held massive promise.

Timothy Leary singing Give Peace a Chance with John Lennon and Yoko Ono

Since then, society, politics, and culture have firmly kept psychedelics in the "vices" category, found at music festivals instead of clinics. But today, studies into these drugs have rediscovered their lost potential, riveting researchers and raising hopes for treatment of PTSD, addiction, cluster headaches, and other ills. But convincing an anti-drug society to accept such a radical new viewpoint, and to do so with evidence, ethics, and scientific backing, will take work for scientists and citizens alike.

A history of controversy

Our culture was not always so opposed to the medical use of psychedelics. In the 1950s and 60s, research into psychedelics, then an entirely novel class of drugs, was rapidly accelerating. Researchers examined each drug’s effects from every psychotherapeutic angle, offering insights from the lab, the patient’s couch, and the doctor’s chair. Studies such as the Concord Prison Experiment sought to reduce prisoner recidivism rates through psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy, while the Good Friday Experiment investigated the power of its subjectively mystical effects on a receptive group of divinity students.

Although promising, the results from these studies were massively overshadowed by the social upheaval brought throughout the US by their principal investigators, Leary and colleague Richard Alpert. Although the pair began as respected researchers at Harvard, their firing coincided with their choice to promote hallucinogens in unique, and distinctly non-academic, ways.

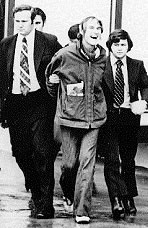

Leary is arrested by agents from the forerunner of the DEA, the Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs

Leary encouraged LSD use across the country, popularizing the phrase "turn on, tune in, drop out," and raised enough of a ruckus to be deemed "the most dangerous man in America" by then President Richard Nixon. Alpert continued his psychology experiments until he was fired by Harvard, at which point he went on a spiritual quest to India and changed his name to Ram Dass, culminating in the bestselling book, Be Here Now.

The rest is history: the government outlawed all hallucinogens in 1968 and universally squashed research on the substances. In the early 1980s, there was a brief period of psychotherapeutic research into MDMA as it first became known, but recreational use quickly captured the spotlight, and MDMA was classified as a Schedule 1 drug (alongside the likes of heroin) in 1985. Despite this 40-year moratorium on scientific investigation, advocates, researchers, and disciples remained hopeful that psychedelics could help answer many of modern man’s ills.

The renaissance begins

It was in this spirit that Rick Doblin founded MAPS, a nonprofit research, education, and advocacy group dedicated to overcoming the obstacles, scientific and legal, that stand between psychedelics and medical acceptance. By any measure, MAPS has been a resounding success; they are the main driver behind what many experts are now calling the “Psychedelic Renaissance.” And we are indeed in a psychedelic renaissance, rediscovering vital knowledge which was criminalized before it could be formalized. MAPS has raised and distributed $20 million dollars to initiate new, scientifically rigorous psychedelic research, and on the back of their promising preliminary results, many additional studies are being funded by a mix of private and public grants.

MAPS founder Rick Doblin

If you are a proponent of psychedelic medicine, then nearly every major finding, newspaper headline, and governmental reevaluation of recent years has been music to your ears. Initial results from studies have been breathtakingly positive. MDMA-assisted psychotherapy so effectively ameliorates PTSD symptoms in Phase II clinical trials, where drug efficacy and safety is tested, that the FDA has labeled the practice a “breakthrough therapy” and accelerated its movement through their approval process. This combination therapy also appears to help treat social anxiety in adults with autism, a population frustratingly resistant to psychiatric medication.

The classical hallucinogens, Lysergic Acid Diethylamide (LSD) and psilocybin, best known as the active ingredient in "magic" mushrooms, can reduce anxiety associated with terminal diseases such as cancer, and they being tested for efficacy in treating both alcohol and nicotine addictions. A strong community of cluster-headache-sufferers swears LSD is the only substance that can break the savagely painful cycles.

Additionally, a group of researchers are hailing ketamine, the dissociative anesthetic, as the biggest breakthrough in depression treatments since SSRIs, now the world's most common antidepressants. Ibogaine, a hallucinogenic substance found in plants native to Africa and the Amazon, seems to almost miraculously relieve people struggling with opioid addictions and may serve as an invaluable tool for overcoming the current crisis. And, of course, marijuana research continues to produce a compelling body of evidence to utilize the drug as a less toxic alternative to pharmaceuticals for a myriad of diseases and disorders.

Although many of these studies are still in their early phases, the preliminary data overwhelmingly supports the use of psychedelics as targeted medicines, specifically in conjunction with psychotherapy. So why is there such intense skepticism about this group of “drugs” in particular? Why is it that cancer chemotherapies with significant mortality rates and harsh side-effects will readily move through the clinical trial phases and directly into use, but LSD, which has nearly zero recorded overdoses, rarely even achieves study approval?

Cultural war on drugs

The answer is likely buried under 50-plus years of drug prohibition and abstinence-only education in the United States and around the world, a culture that has shaped the negative stigma of all psychedelics. Instead of re-litigating this past, though, researchers in the field are posed at the precipice of progressing forward with revolutionary studies, and may conscientiously move our culture forward with them. But moving the culture will require awareness and action from scientists and citizens.

First, people on both sides need to be aware of the pre-conceived notions we bring to the debate. Sometimes biases can be instructive – the researchers who first forged this path followed their belief that psychedelics are important and useful, even before they had rigorous evidence to back up their claims. But this faith is a double-edged sword, and we must remain truly willing to reconsider beliefs in light of new evidence, or it will be impossible to convince the broader public to do the same.

Second, researchers in this field have a remarkable opportunity, and responsibility, to properly communicate their findings and recommendations with the public, a task that will be vital for psychedelics to achieve not only medical, but cultural, integration. It is important to remember psychedelics are not the ultimate panacea for treating mental health concerns.

However, with time, and reams of further research, they may become invaluable components of the medical and mental health toolkit at a time when the need for these tools is rising.

Max Planck, the quantum physicist and Nobel laureate, once quipped an apparent law of progress, that “science advances one funeral at a time.” But if we are all able to borrow a page out of the psychedelic playbook, and open our minds to new evidence, ideas, and each other, we might yet revolutionize the relationship between science, society and our daily lives.