Allan Lasser

How Shark Week hurts the very creatures it celebrates

Showing attacks makes people less likely to support protecting sharks, though they rarely bite people unless we harm their food system

Discovery Channel’s Shark Week is a conflicted time of the year for a marine ecologist. It’s an entire week dedicated to an awe-inspiring, vital, and under-appreciated class of fish that draws a record number of viewers. For me and my immediate family, Shark Week, which began on Sunday, is akin to a holiday: we get together, wear various shark apparel, and celebrate our favorite type of animal.

But over its 29-year history, Shark Week has increasingly strayed into dramatized and sensational programming, creating media that defines our view of sharks as creatures to be avoided and feared—and not necessarily conserved. Much of its programming focuses on shark attacks. As a perennial viewer, I’ve even noticed that certain attacks have been reused in programming from year to year, probably out of necessity given the extremely low number of attacks globally (I’m not the only person who has noticed this).

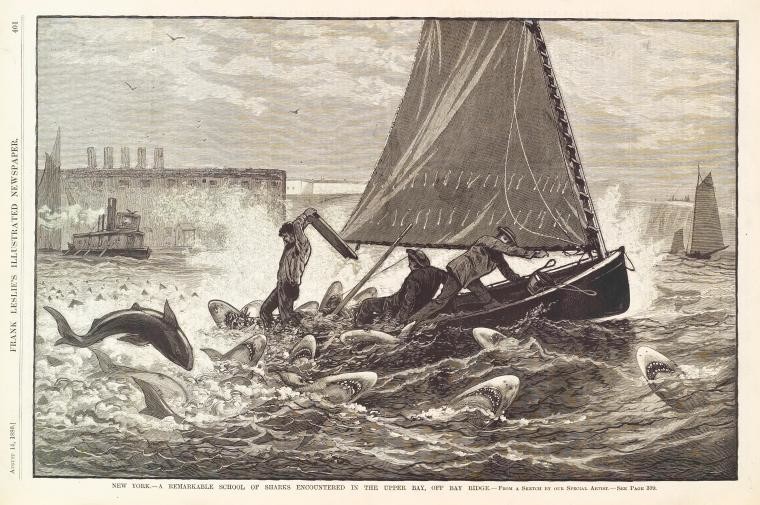

"A remarkable school of sharks encountered in the upper bay, off Bay Ridge."

This all matters because our inaccurate attitudes toward sharks result in harmful policy responses. It's a phenomenon that Christopher Neff, a public policy professor at the University of Sydney, calls the Jaws effect: consistently focusing on shark attacks translates to increased fear of sharks in viewership, and this trepidation manifests itself in a fear-based shark mental shortcut that allows the creation and implementation of unscientifically sound shark culling programs. And since sharks are vital to the ocean's food ecosystem, killing them out of unfounded fear disrupts food supplies on the entire planet.

This isn't an idle fear: in a seminal 2014 paper, two researchers from Indiana University and University of North Carolina subjected 531 participants to violent or non-violent video clips of shark footage from Shark Week, followed by one of two types of public service announcement regarding shark conservation. Viewers subjected to more violent shark footage reported significantly increased fear of sharks and a greater perceived threat from sharks. The PSAs, with or without a celebrity spokesperson, did not assuage perceived fears of shark inspired by the footage, nor did the PSAs make the violent shark footage seem exaggerated or dramatic. Though they did inspire increased intention to support shark conservation, more effective than PSAs would be to stop running sensationalism that made us fear sharks to begin with.

The Jaws effect isn’t unique to Shark Week; a 2013 study found that 59 percent of shark-related news articles in Australia and the US focused on negatives associated with sharks. More than half of the 300 articles examined in this study focused on bite incidents, while only 11 percent broached conservation issues. Beyond news media, blockbuster movies like Jaws, The Shallows, and even the silly Sharknado build features around the premise of sharks as mindless, malicious man-eaters.

Nothing exemplifies this better than the public response following the release of Jaws. The 1975 Spielberg film provided vivid imagery of a rogue, man-eating shark that inspired a shark-killing frenzy, with the advent of shark tournaments and bounties across the world.

A scene from Steven Spielberg's 1975 film Jaws.

Film still reproduced under fair use via The Daily Jaws

The science of the Jaws effect

Neff’s Jaws effect is underpinned by the desire to cast blame when something goes wrong—in this case, when shark bites occur. And blame requires holding a common mindset or belief about who’s responsible. Neff reiterates that Jaws and other shark horror media provide a “mental shortcut” for casting blame. In the case of sharks, it's the readily available judgments and associations about sharks that we quickly draw upon when bites occur, or even when we just think about water, swimming, or sharks.

This mental shortcut idea appears in extensive neuroscience and psychology work related to fear conditioning, pioneered by Joseph Ledoux in the book The Emotional Brain. To paraphrase Ledoux’s elegant work, fear conditioning essentially says that when immersed in a scary or dangerous situation, your brain and body both respond. When presented with some cue or stimuli related to the scary experience down the road, you call up the created mental shortcuts subconsciously and return to your emotional fear response. Essentially your brain draws from emotional information most readily accessible . Unluckily for our rational reasoning skills, fear creates a strong and long-lasting emotional memory because it's rooted in the fight or flight responses necessary for survival.

In the case of the Jaws effect, Neff has written that movies and TV that highlight shark-on-human violence ingrain three common narratives in viewers, in creation of this culturally shared shark mental shortcut:

- Sharks that bite humans do so intentionally.

- When sharks bite it’s fatal.

- Rogue sharks are responsible for bites, and we must hunt the shark that bit.

Despite the fact that each of these storylines are readily disproved with facts (e.g. here, here, and here), this common set of mental shortcuts pervades and goes on to inform scientifically unsound shark policy.

14-foot, 1200 pound tiger shark caught in Kaneohe Bay, Oahu, Hawaii where they are hunted for only a small part of their bodies.

Photo by Dr. James P. McVey, NOAA Sea Grant Program, via Wikimedia Commons

In his 2015 paper Neff specifically cites three specific policy responses by the West Australian government rooted in the unsound Jaws mindset. Most recently, Neff highlights their 2013–14 policy that allowed for the pre-emptive killing of individual sharks to ward off the possible threat of bites. The preemptive nets and long-line fishing designed to prevent bites didn’t kill a single great white, but they did catch plenty of other non-target marine species, significantly harming the overall food web in the area. And bites in the region continue, despite recent and historical culls.

This story has played out across the globe with equally ineffective results. In Hawaii, sharks were culled during the 1960s and ’70s with no reduction in bites; recent tagging research implicates habitat preference as the primary driver of shark density, with new sharks moving into preferred areas upon the elimination of other sharks. Overall, the Jaws effect and cull programs resulting from an inaccurate shark mental shortcut mean that sharks are demonized and killed, taxpayer money is wasted, and no one is safer.

I initially found all this somewhat far-fetched: how can one non-traumatic experience, like watching Jaws, have such a long-term influence on a person? Then I remembered my latest vacation. While surfing in California, the infamous “dun dun, dun dun, dun dun” refrain started playing in my head as I was waiting between waves. And I’m a trained marine biologist, familiar with the importance of sharks and the extremely low odds of an attack—I’ve swam and dove with sharks for years now. Yet there I was, hearing the Jaws theme song in my mind and feeling a little scared.

Facts can be fun too

We know that media focusing on shark violence makes us negatively perceive sharks. We know that these shows and films create fear-based mental shortcuts that resound in our personal actions as well as large-scale policy outcomes.

Yet I can’t bring myself to throw in the towel on Shark Week; its popularity makes it a primary avenue for millions of viewers to receive necessary information about sharks. And as additional evidence from O’Bryhim and Parsons suggests, increased knowledge about sharks translates to increased proclivity to support shark conservation. In other words, there can be a sweet spot where shark attack entertainment doesn't outweigh useful information.

Sharks are the best!

Photo by the author

Getting people to learn the actual facts about sharks is vital, because our Jaws effect policies are harming far more than individual sharks. Despite their vital role in regulating food webs, sharks and other top predators are in steep decline; some estimates suggest 100 million sharks per year are slaughtered, with upper estimates suggesting 267 million sharks may be killed in a single year; some populations have already been reduced by up to 90%. Shark finning, or the practice of killing mass numbers of sharks only for their fins, is a particularly damaging and gruesome type of top predator removal that is throwing marine food webs drastically off-kilter.

And, irony of ironies, this is why sharks end up biting people the few times they do: because we are seriously screwing up the balance of marine food webs that sharks rely on. We've accomplished this by taking away food sources via overfishing, removing natural competitive processes, changing overall water quality and habitat, and changing the climate. All these altercations increase the probability for shark-human interaction as sharks are forced to figure out new ways to cope in degraded, often food-scarce, environments.

Shark Week fans should reach out to the Discovery Channel and clamor for increased information about shark finning, exciting ongoing shark research, or one of the little known but extremely interesting species of shark beyond tiger sharks, white sharks, hammerheads, and bull sharks. The line-up this year looks decidedly hopeful, but only continued pressure from consumers will ensure that Shark Week and other outlets responsibly portray sharks as the vital and respected predators they are, for their sake and for ours.

Featured Articles

- Muter et al. 2013. Australian and US News Media Portrayal of Sharks and Their Conservation. Conservation Biology 27:1, 187-196. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2012.01952.x

- Myrick and Evans. 2014. Do PSAs take a bite out of Shark Week? The effects of juxtaposing environmental messages with violent images of shark attacks. Science Communication 36:5, 544-569. https://doi.org/10.1177/1075547014547159

- O'Bryhim and Parsons. 2015. Increased knowledge about sharks increases public concern for their conservation. Marine Policy 56, 43-47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2015.02.007

- Neff. 2015. The Jaws Effect: How movie narratives are used to influence policy responses to shark bites in Western Australia. Australian Journal of Political Science 50:1. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10361146.2014.989385