James Gathany/CDC

Saliva is just what we needed to create a new malaria vaccine

The mistake mosquitos made? Leaving their spit behind

Malaria is one of the leading killers of children under 5. There's a vaccine currently available in three African countries, the RTS,S vaccine, and it is undoubtedly a massive step forward. But, it’s still only partially effective: in a large clinical trial, the vaccine only prevented about 30% of cases of severe malaria. The fight against malaria is far from over.

Researchers have been working on malaria vaccines since the 1940s, with limited success. These previous conventional vaccines attempted to help the human immune system recognize the parasites that cause malaria (called Plasmodium), but this has proved to be an extremely difficult task.

Although there have been issues with limited funding, much of this difficulty in creating an effective vaccine has come from the incredible complexity of the Plasmodium parasite. Its genome is made up of 23 million base pairs. While that’s 130 times fewer base pairs than a human, it’s 115 times more base pairs than, say, the smallpox virus. Plasmodium has a complex life cycle – progressing through multiple tissues in two different host species and undergoing ten morphological changes over the course of its life. Constantly changing, it skillfully evades the immune system of its host.

But now researchers at Yale are coming at the problem from a different angle. Since the vast majority of malaria infections occur when a person is bitten by a mosquito which transmits the Plasmodium parasite, what if we didn’t need the immune system to recognize the parasite itself? What if we just needed to recognize the mosquito?

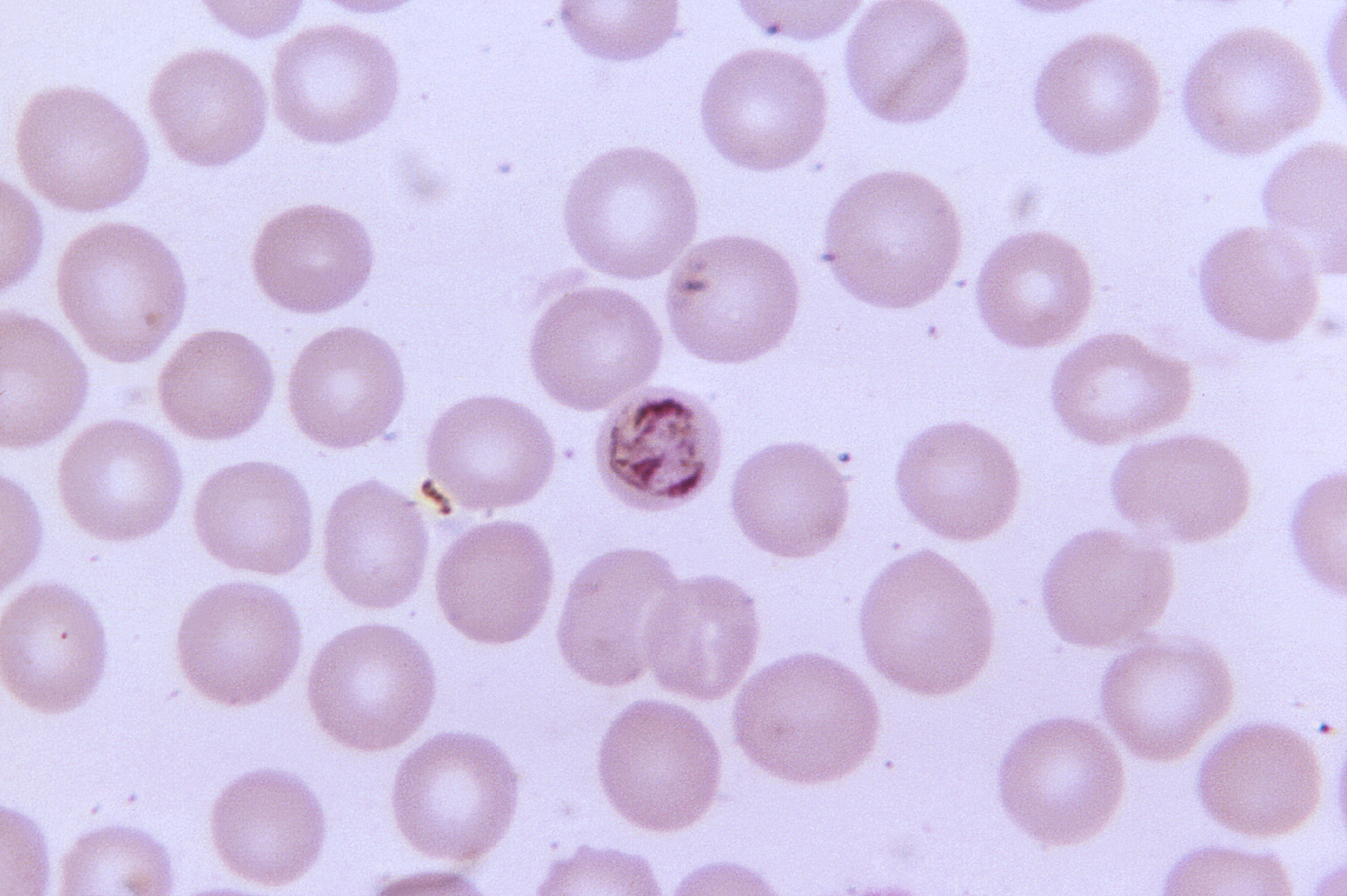

This is what Plasmodium looks like, just in case.

CDC/ Dr. Mae Melvin

They gave it a go. The researchers at Yale have created a vaccine not against the parasite itself, but against the mosquito saliva that carries the parasite into the human body. Yes, mosquito spit.

More specifically, the vaccine teaches the immune system to recognize a protein in mosquito spit called AgTRIO. To do this, they created a vaccine containing the AgTRIO protein itself and an adjuvant (a substance designed to heighten the immune response). Mice who received the AgTRIO vaccine before being exposed to infected mosquitoes ended up with significantly fewer parasites in their blood compared to their counterparts who had received an inactive vaccine.

Unfortunately, it didn’t provide complete protection – some of the immunized mice still had parasites. So researchers wondered what would happen if this partially effective strategy was combined with another partially effective strategy, like the more conventional RTS,S vaccine. RTS,S teaches the body to recognize a Plasmodium protein called circumsporozoite protein, or CSP.

When researchers gave mice vaccines against both AgTRIO and CSP, they were almost completely free of parasites – a much stronger result than either vaccine administered alone. Thus, researchers believe that an AgTRIO vaccine might be able to act synergistically with the RTS,S vaccine – a combo that could provide much more effective protection against malaria.

But how does this work? Why does immunizing against spit help protect against a parasite? As weird as it seems, spit actually seems to play a big role in how blood-sucking bugs transmit infections to humans (or other animals) that they feed on. For example, tick saliva may increase the infectiousness of the bacteria that causes Lyme disease by altering responses of the host immune system. So it’s possible (although still controversial) that Plasmodium is getting a boost from mosquito spit. Interestingly, researchers still don’t know what AgTRIO does – so they’re not sure exactly how the vaccine against it helps to protect against Plasmodium. They do know that the AgTRIO vaccine caused the parasites to move more slowly through the skin of the host, which perhaps impeded their ability to cause a full-blown infection.

.jpg)

Spit: pretty good and fun actually.

Serge Melki via Wikimedia Commons

Immunizing against spit has other advantages too. The currently approved malaria vaccine only protects against infection by one species – Plasmodium falciparum. There are over a hundred species of Plasmodium and at least five of them cause disease in humans. Since the fifth – Plasmodium knowlesi – was only discovered to commonly infect humans in 2004, it’s possible that there could be more species infecting us that we have yet to discover. However, since all the Plasmodium species are accompanied by mosquitoes and their saliva, a spit vaccine could potentially provide much broader protection. It's possible that it could even provide protection against other diseases (like the O’nyong nyong virus, which infects people in East Africa) that are carried by Anopheles mosquitoes, although this has not yet been proven.

There’s still a lot of work to be done before the AgTRIO vaccine is ready to be tested on humans, but this study is potentially an important step in developing a more effective malaria vaccine that could save hundreds of thousands of lives. And with the rise of drug-resistant malaria, vaccines are needed more than ever.

Thanks for conveying a cool story. Could increasing the immune response to AgTRIO, which presumably has a significant concentration at the site of the bite, generate itchier and more painful bites via enhanced localized inflammation? It would be a small price to pay for not having a potentially deadly disease. That also makes me wonder if people who already have bad reactions to things like mosquito bites, bee stings, etc. may have some resistance to infectious diseases for the same reason.