A version of this story originally appeared on Kaiser Health News

The lifesaving transplant organ you're waiting on may go missing in transit

A new investigation finds that many organs are critically delayed while being shipped on commercial airliners

When a human heart was left behind by mistake on a Southwest Airlines plane in 2018, transplant officials downplayed the incident. They emphasized that the organ was used for valves and tissues, not to save the life of a waiting patient, so the delay was inconsequential.

“It got to us on time, so that was the most important thing,” said Doug Wilson, an executive vice president for LifeNet Health, which runs the Seattle-area operation that processed the tissue.

That high-profile event was dismissed as an anomaly, but a new analysis of transplant data finds that a startling number of lifesaving organs are lost or delayed after being shipped on commercial flights, the delays often rendering them unusable.

In a nation where nearly 113,000 people are waiting for transplants, scores of organs — mostly kidneys — are discarded after they don’t reach their destination in time.

Between 2014 and 2019, nearly 170 organs could not be transplanted and almost 370 endured “near misses,” with delays of two hours or more, after transportation problems, according to an investigation by Kaiser Health News and Reveal from the Center for Investigative Reporting. The media organizations reviewed data from more than 8,800 organ and tissue shipments collected voluntarily and shared upon request by the United Network for Organ Sharing, or UNOS, the nonprofit government contractor that oversees the nation’s transplant system. Twenty-two additional organs classified as transportation “failures” were ultimately able to be transplanted elsewhere.

Surgeons themselves often go to hospitals to collect and transport hearts, which survive only four to six hours out of the body. But kidneys and pancreases — which have longer shelf lives — often travel commercial, as cargo. As such, they can end up missing connecting flights or delayed like lost luggage. Worse still, they are typically tracked with a primitive system of phone calls and paper manifests, with no GPS or other electronic tracking required.

“We’ve had organs that are left on airplanes, organs that arrive at an airport and then can’t get taken off the aircraft in a timely fashion and spend an extra two or three or four hours waiting for somebody to get them,” said Dr. David Axelrod, a transplant surgeon at the University of Iowa.

One contributing factor is the lack of a national system to transfer organs from one region to another because they match a distant patient in need.

Instead, the U.S. relies on a patchwork of 58 nonprofit organizations called organ procurement organizations, or OPOs, to collect the organs from hospitals and package them. Teams from the OPOs monitor surgeries to remove organs from donors and then make sure the organs are properly boxed and labeled for shipping and delivery.

From there, however, the OPOs often rely on commercial couriers and airlines, which are not formally held accountable for any ensuing problems. If an airline forgets to put a kidney on a plane or a courier misses a flight because he got lost or stuck in traffic, there is no consequence, said Ginny McBride, executive director of OurLegacy, an OPO in Orlando, Florida.

Scores of organs — mostly kidneys — are trashed each year and many more become critically delayed while being shipped on commercial airliners, a new investigation finds.

By Robina Weermeijer on Unsplash

In an era when consumers can precisely monitor a FedEx package or a DoorDash dinner delivery, there are no requirements to track shipments of organs in real time — or to assess how many may be damaged or lost in transit.

“If Amazon can figure out when your paper towels and your dog food is going to arrive within 20 to 30 minutes, it certainly should be reasonable that we ought to track lifesaving organs, which are in chronic shortage,” Axelrod said.

For years, organs were distributed locally and regionally first, a system that resulted in wide disparities in organ waiting times across the country. In recent years, UNOS officials and the transplant community, with federal urging, have been working, organ by organ, to restructure how it’s done.

Amid those ongoing efforts to allocate organs more fairly — and, recently, a Trump administration effort to overhaul kidney care — the waste of some of these precious resources donated by good Samaritans has been overlooked.

Donor families and waiting patients may never know what’s happened to an organ provided by a loved one or why a surgery is canceled at the last minute.

“We have been unaware of how many kidneys have been waylaid,” said McBride, of the Orlando procurement agency. “That’s not a number that’s been transparent to us.”

But, she added, she’s aware of the risk: “I say a prayer and hold my breath every time a kidney leaves our office.”

46 Minutes To Spare

In October, a kidney en route from McBride’s OPO in Florida to a patient in North Carolina missed its connection in Atlanta. The box was prominently marked as a human organ and displayed a phone number to call. Apparently unaware of the urgency, a Delta cargo worker merely set it aside for a later flight.

The waiting transplant surgeon in Greensboro, North Carolina, “was having a fit,” said Kim Young, the OurLegacy organ recovery coordinator. If the kidney didn’t get to the hospital by 7 a.m., he wouldn’t be able to use it. Both the risk of organ failure and the chance of death increase with every hour a kidney is out of the body.

McBride had to decide whether to charter a plane at a cost of $15,000 — or to find a courier to drive the kidney through the night. She settled on the road trip, and the organ arrived at 6:14 a.m. — with just 46 minutes to spare.

Delta Air Lines officials declined repeated requests to comment on its organ transport service or the specific incident McBride described.

Several domestic airlines, including Delta, United, American, Southwest and Alaska, provide special cargo services for organs with priority boarding, handling and monitoring. They all declined to comment on organ transportation.

The traveling public may not realize it, but thousands of transplant organs — mostly kidneys, but some pancreases — fly on commercial flights each year. Roger Brown, who runs the Organ Center at UNOS, estimates that as many as 10 organs for transplant are on the move this way every day.

Kidneys make up a large number of transplant organs.

By Robina Weermeijer on Unsplash

UNOS handles about 1,800 of these organ and tissue shipments a year, of which 1,400 are kidneys. That’s a fraction of the nearly 40,000 organs transplanted in the U.S. last year, including more than 23,000 kidneys. About 1 in every 6 transplanted kidneys is shipped nationally, UNOS figures show.

Most of the time, the organs get where they’re going without incident, Brown said.

“We’re never going to get rid of flight delays. We’re never going to get rid of human error,” he said. “We’re never going to get rid of the person who’s [trying to be] a little too helpful and perhaps puts it someplace special, which then maybe creates issues downstream.”

Troubling Reports

Reports of trouble abound. In August, transplant officials at Medical City Dallas reported in a public forum that they’d lost three kidneys just that month because of problems with commercial flights.

“One organ was delayed due to weather and the next available flight wasn’t till the next day,” the report said. “Another organ made it to the airport, but was never placed on the intended flight. The third organ was mistakenly taken to the wrong airport and missed the intended flight.”

In Kentucky, transplant surgeon Dr. Malay Shah said a kidney traveling on Delta from Pensacola, Florida, via Atlanta, on Oct. 1 sat in the Lexington airport for three hours before he was notified it was there. No one had noticed the box with the label that said “human organ for transplant,” he said.

“It’s scary,” Shah said. “Organs traveling by this mechanism are treated as simply ‘baggage’ or ‘cargo.’”

Before the 9/11 terror attacks in 2001, OPO workers could take organs through airport security and see them loaded onto the plane from the passenger gate, McBride said.

While anecdotes like Shah’s are common, there’s little data to show how often these transportation problems occur. No federal agency, including the Health Resources and Services Administration, or HRSA, which contracts with UNOS, requires monitoring of transportation for transplant organs.

“Matters involving the transportation methods used by organ procurement organizations (OPOs) are arranged directly between OPOs and transplant centers,” HRSA spokesperson David Bowman said in an email.

Airlines log organ shipments in internal booking systems and on cargo manifests, but those documents aren’t public and no summary is available, said Katherine Estep, communications director for Airlines for America, an industry trade group.

“Live human organs receive the highest priority designation,” she said in a statement.

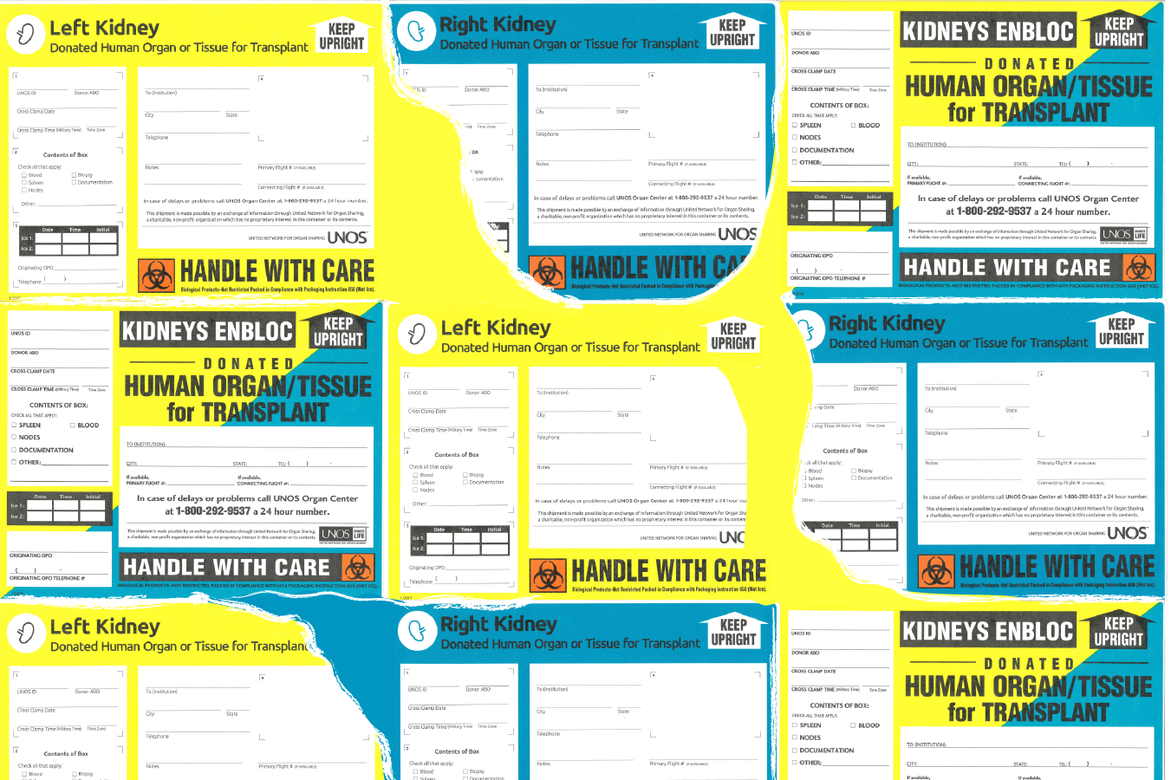

Teams from organ procurement organizations, or OPOs, monitor surgeries to remove organs from donors and then make sure the organs are properly boxed and labeled for shipping and delivery.

Hannah Norman/KHN Illustration; Labels courtesy of Ginny Mcbride

UNOS researchers noted the impact of transportation problems in 2014. They found 30 organs discarded and 109 “near misses” between July 2014 and June 2015.

But the agency didn’t begin formally tracking transportation errors until 2016, when a new computer system came online. Before that, Organ Center staff kept track of problems informally, with pencil and paper, and the information wasn’t verified, Brown said.

Calls for closer tracking from within the system have been met with defensiveness — or apathy, said Brianna Doby, an organ transplant community consultant for the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine.

“If you talk out loud about organ issues, they say it will drive down donation rates,” Doby said. “It’s not OK for us to say, ‘Well, shipping is hard.’ That’s not an acceptable answer.”

A National Network

UNOS was established in 1984 after Congress enacted the National Organ Transplant Act to address a critical shortage of donor organs and to improve organ matching and placement. It called for a national network to ensure that organs that couldn’t be used in the area where they were donated, and would be transplanted to save lives elsewhere. Before that, many organs were lost simply because transplant teams couldn’t find compatible recipients in time.

The act established the national Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network and called for the OPTN to be operated by a private, nonprofit organization under federal contract. UNOS, which has held the contract since the inception of OPTN, is overseen by HRSA, an agency of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Today, UNOS typically handles organs with conditions that can make them hard to place. That can include organs from older donors or those with medical or other characteristics that make them difficult to match.

The National Organ Transplant Act called for a national network to ensure that organs that couldn’t be used in the area where they were donated, and instead would be transplanted to save lives elsewhere.

By Free-Photos from Pixabay

Overall, about 7% of shipments handled by UNOS from July 2014 to November 2019 encountered transportation problems, the data obtained by KHN and Reveal showed. UNOS wouldn’t release details about individual shipments, including dates or places shipped or causes of the transportation failures or delays.

But Brown, of the UNOS Organ Center, said an internal analysis showed that more than half of the transportation problems were related to commercial airlines or airports. Of those, two-thirds were caused by weather delays, mechanical delays and flight cancellations.

About one-third of transportation problems were related to logistics providers or ground couriers, mostly delays of package pickups. The rest were related to the sender or receiver of the shipments.

However, Brown said, poor outcomes can’t be blamed directly on transportation problems, even when they do occur.

“The delay could be the primary reason an organ wasn’t transplanted,” he said. “It could be a contributing factor or it could have nothing to do with the reason that the organ is not transplanted.”

Other transplant experts downplay the impact of transportation problems. Kelly Ranum, president of the Association of Organ Procurement Organizations, said she’s “surprised at how low” UNOS’ failure numbers are, considering the volume of kidneys shipped.

Dr. Kevin O’Connor, chief executive of LifeCenter Northwest, an OPO based in Seattle, said transportation problems are “minimal” compared with the other reasons organs — including about 3,500 donated kidneys — are discarded each year. These typically include biopsy findings, the inability to find a recipient and poor organ function.

“For over 30 years and literally tens of thousands of organs being transported,” he said, “I can count on the fingers of one hand the number of times that, because of a transportation glitch, an organ was ultimately not transplanted.”

Still, O’Connor acknowledged that “even one kidney being thrown away because of transportation errors is unacceptable.”

Other than transit delays, organs can be discarded due to biopsy findings, the inability to find a recipient, and poor organ function.

Rawpixel.com on Pexels

Part of the problem lies with the way organs are transported now, said Axelrod, who also represents the American Society of Transplant Surgeons.

“We don’t have an end-to-end unified transportation system,” Axelrod said. “We don’t have a FedEx for transplant. We have a cobbled-together system of OPOs and couriers and private aircraft and commercial aircraft.”

In recent years, several courier companies have emerged to meet the market for transplant organs. Don Jones, chief executive of the Nationwide Organ Recovery Transport Alliance, or NORA, contracts with more than 15 OPOs and oversees about 400 organs a year on commercial flights.

“I would say 99.8% of our transports on commercial airlines go perfectly fine,” Jones said based on his estimate. Jones noted that his firm ships organs only on direct flights and uses GPS tracking to monitor them.

Some couriers and airlines use it; many don’t. Many OPOs monitor organs through a combination of verbal handoffs, automation and label scans, Brown said.

In Ginny McBride’s misadventure last fall, she contracted with a courier, Sterling Global Aviation Logistics, which used Delta Air Lines to ship the kidney.

Delta uses GPS trackers on its Dash Critical shipments, promising fast, guaranteed delivery of human organs. But on that night in October, the kidney was shipped from Orlando to Atlanta without a GPS tracker. In Atlanta, a cargo worker couldn’t find a GPS device to put on the box containing the kidney, so the worker held the organ for a later flight. That would have pushed it far beyond the window of viability.

An internal Delta report, obtained by McBride, found that Delta didn’t have enough GPS devices available in Atlanta that night. “Destination stations are not returning the devices in a timely manner,” according to the report. “One way to mitigate this from reoccurring is to have a larger inventory of GPS devises (sic) at each station.”

Delta declined to comment on the report.

Average national wait times for a kidney transplant vary widely.

Icons8

The average wait time for a kidney varies widely nationwide, from less than three years to more than a decade. One proposal to put more organs to use called for eliminating the 58 donation service areas and 11 regions now used to allocate kidneys and replacing them with a zone of up to 500 nautical miles from the donor hospital.

In December, OPTN cut that range in half — to 250 nautical miles — in part because of an outcry about problems shipping kidneys via commercial air.

“There are certainly no technological barriers to doing GPS and to actually requiring it,” Brown said.

A UNOS committee is considering whether to collect data on transportation methods and outcomes, but, so far, the question remains under review.

“If the community wants it, they should ask for it,” Brown said. “We can help facilitate and get it done for them.”

McBride, who discussed solutions with her colleagues, hopes the transplant organizations will come together to solve transportation problems, to make sure every eligible donated kidney gets transplanted.

“Any organ that’s wasted, in my opinion, is a loss to the patient and to the community,” said Paul Conway, of the American Association of Kidney Patients, an advocacy group, who is himself a kidney recipient. “With all of the advances going on with drugs, with medical procedures, how can you have a logistics error be the barrier?”