Photo by Katherine Hanlon on Unsplash

Alternative medicine could treat our maladies, but we have to study it

It is sorely lacking in rigorous scientific research

Scientists are trained to question claims that are not supported by data. In the west, eastern traditional medicines have been largely criticized for their air of mysticism. However, we cannot debunk a field that is not well-studied. Alternative medicine can become an actual science if we implement rigorous research and strict regulatory policies. Ultimately, it can become successfully integrated into conventional therapy to improve health outcomes.

Not all alternative medicine that are available have been extensively studied. Researchers at University of Maryland looked at 70 other studies of alternative medicines to measure the effectiveness of alternative medicine. They determined that these studies provided sparse evidence with poor quality. Of the 42 reviews on Chinese herbal medicine, 47% failed to produce quality evidence to conclude whether or not the treatment was potentially effective. Even among commonly used herbs (Ginseng, ginkgo biloba, garlic, St. John’s wort, soy, and kava), there has been poor methodology, inconsistent outcome measurements, and conflicting results.

The data was collected from trials with non-standardized methods. Some trials carried a high risk of bias. In addition, the heterogeneity of the trials did not allow for a meta-analysis to be performed, which meant that data from independent experiments couldn't be compared, making it impossible to reconcile disparate findings. And because the majority of these studies were carried out in China, which lacks infrastructure for robust clinical trials, their quality isn't on par with other trials. So, the studies were non-compliant with CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) recommendations, which establishes a standard method for scientists worldwide to report randomized trials.

Alternative medicine is often perceived as "natural" and therefore harmless. However, like any other medication, alternative medicine can have negative side effects and drug interactions that need to be considered. For example, St. John’s wort, one of the most commonly used herbal supplements, has shown efficacy to treat mild to moderate depression and menopausal symptoms. However, St. John's wort interacts with a variety of drugs (ie. chemotherapy, immunosuppressive, and contraceptive drugs) and decreases their activity.

Herbal teas are a common alternative medicinal treatment

Photo by 五玄土 ORIENTO on Unsplash

Another facet of this misrepresentation is through unwavering traditional beliefs that are deeply rooted in cultural identity. For example, rhinoceros horn and tiger bone is still used in China, and across East Asia, to treat impotency and fevers – even though there have been no scientific studies showing any medical benefits.

With a lack of knowledge, people cannot sift through the many studies that prove and disprove an alternative treatment. However, we should not automatically allow the treatments that do not work to tarnish the reputation of those that may actually be helpful. Well-controlled, transparent experiments should be developed to test different alternative therapies. Then, we can raise awareness of their correct usage.

Alternative medicine has a long, rich history in different cultures, and we can extract valuable information from detailed accounts that span centuries. In China, there are many small shops, shelves stacked with glass jars of miscellaneous dried plants, twigs, and fruits. At these shops, herbalists pull out an eclectic array of ingredients, telling their patients to boil them together and drink the liquids to treat their migraines, stomach pains, and fatigue.

In addition, ancient texts that support modern traditional medicine are readily available from research institutes, university libraries, and museums. This "treasure house" harbors the fourth century “Handbook of Prescriptions for Emergencies”, written by Ge Hong, an alchemist, herbalist, and physician. In what is perhaps the biggest alternative medicine success story, this ancient handbook led scientist Youyou Tu to discover the 2015 Nobel Prize winning anti-malarial drug, artemisinin.

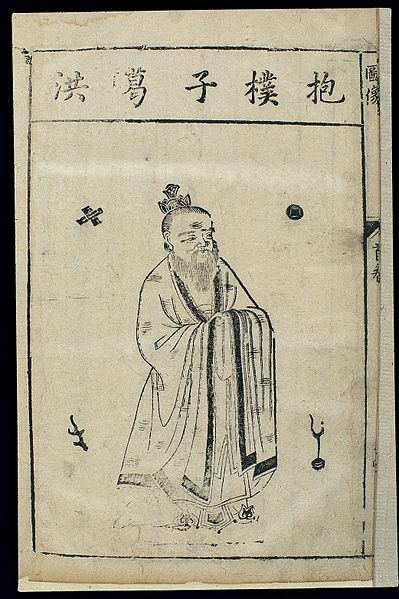

Alchemist, herbalist, and physician Ge Hong

Wellcome Images on Wikimedia Commons

In 1967, China established a national project to search for antimalarial drugs among traditional Chinese medicines. Tu and her team collected 2,000 Chinese herbal recipes from 640 herbs, which was then narrowed down to a few promising candidates, including Qinghao (Artemisia annua L., or sweet wormwood). The Qinghao extract showed effective suppression of rodent malaria (68% inhibitory rate), but the results were inconsistent in repeated tests.

As Tu scoured the medical literature again, she stumbled upon Ge Hong’s handbook, which reported: “use a handful of Qinghao immersed in 2L of water, wring out the juice, and drink it in its entirety” to treat malaria-like symptoms. This triggered a new insight, in that their conventional extraction step, which involved high heat, might have destroyed the active components. Their redesigned experiments, in which the stems and leaves of Qinghao were extracted using reduced temperature, allowed them to isolate chemically pure artemisinin. Subsequent clinical trials on malaria-infected patients showed that artemisinin and its derivatives eliminated malaria species at all stages of the parasite's life cycle. This scientific breakthrough discovery had successfully repurposed an archaic, pseudo-scientific observation into a novel drug that saved hundreds of thousands of lives.

There have also been various publications that discuss the health benefits associated with certain dietary supplements and other holistic approaches. One prime example is gingerol, which is the active ingredient in ginger. The mechanism of action of ginger for relieving chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting has been extensively mapped out. Thunder god vine, likewise, is being developed as a drug for rheumatoid arthritis, and green tea has become a featured ingredient in nutritional supplements for its wide-range of beneficial effects. Other clinical trials have been carried out to show the curative effect of acupuncture on tumor complications and side effects of chemotherapy.

We need to promote the safe and effective use of alternative therapies through better research, stricter regulations, and more extensive understanding of how they can be integrated into conventional medical approaches. The complexities of integrative medicine requires us to rethink our mindset. We can use the tools of the present to bring traditional beliefs into the realm of science.

We only have to look to the numerous plant derivatives used to this day to see the importance of studying “alternative” medicine: morphine from the poppy plant for diarrhea, cough, and pain, a precursor to aspirin from willow tree leaves for pain and inflammation, digoxin from foxglove for various cardiac conditions, quinine from cinchona tree bark for malaria, and the list goes on. Nearly a thousand years ago, Ibn Sina (Avicenna), considered to be the father of early modern medicine, wrote “The Canon of Medicine”, including a Formulary (Book 5) listing 650 drugs. Ayurvedic medicine has used Mucuna pruriens for Parkinson’s disease, a treatment described in a small trial and case report, both stating that larger trials are needed to understand the tolerability and efficacy. Somehow, traditional Eastern approaches became grouped together with homeopathy and are largely discounted by the scientific community. Song-My’s article does an excellent job at demonstrating the need for us to know and respect our medicinal history and apply current, rigorous research methodologies to know traditional medicine’s place in the modern world.