Lab Notes

Short stories and links shared by the scientists in our community

Prehistoric white sharks can help us save sharks in modern day

How researchers found a two to five million year old shark nursery

White sharks may have a guaranteed spot on Shark Week but there is still a lot to learn about this famed fish.

Sharks have been around for millions of years. The earliest fossil of Carcharodons, the genus of the white shark, dates back to 16 million years ago. Yet today, white shark populations are considered vulnerable to becoming endangered due to overfishing.

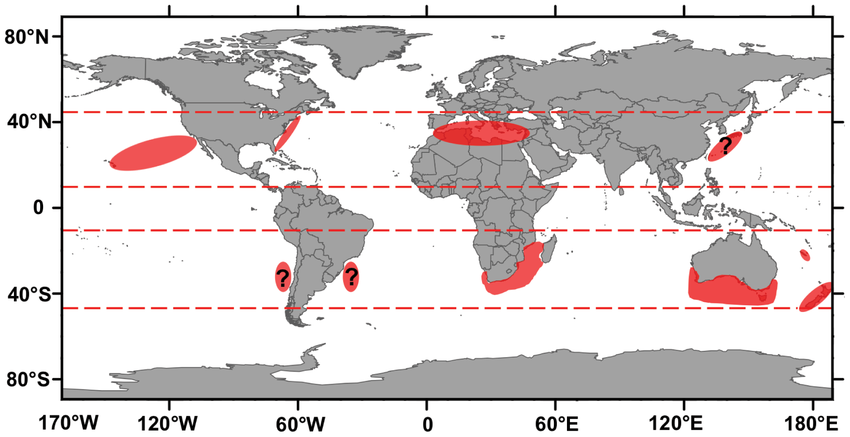

Protecting these sharks can be tricky. There are white shark aggregation sites around the world, but each of these populations have different behaviors and migratory patterns. Scientists are studying each existing population to inform local policy and management.

White shark hot spots

It isn't just modern populations of sharks that can provide us with useful insight. Understanding how white sharks thrived millions of years ago could help us protect them today.

Researchers have proposed a location in Coquimbo, Chile as a nursery for white sharks during the Pliocene Epoch, a period of geologic time that spans from 5.33 million to 2.58 million years ago.

A nursery habitat is an area that contributes more juveniles of a species to the adult population compared to other areas. To be considered a nursery, the area in question had to fit three criteria: be a shallow water environment, have an abundance of resources, and be dominated by juveniles white sharks.

Shark tooth

The researchers collected white shark fossil teeth from three different places. They used measurements of the teeth to estimate the total length of the individual sharks. The total length of a juvenile white shark was considered to be between 175 cm to 300 cm. In Coquimbo, there was a higher proportion of juveniles compared to the other study sites. The researchers also found signs of potential prey species and evidence that this area was once a shallow-water marine habitat.

Nursery habitats helped protect young sharks millions of years ago. Identify and conserving modern nursery habitats could be an important factor in keeping white shark populations stable today.

Guinea pig evolution can teach us about human history in the Americas

Indigenous people kept them as pets and traveled with them over 1000 years ago

Adriana L. Romero-Olivares

Guinea pigs are pets, they’re culturally important, they're food, they're therapy animals, and they are “guinea pigs” in scientific research. You may have seen or heard of them, and wondered if they're enormous hamsters, or just pigs from Guinea — but they are none of these things. Guinea pigs are domesticated rodents from the Americas and they’ve been associated with humans for up to 7000 years.

Guinea pig trade outside of the Americas, started in the late 15th century when Europeans introduced them to Europe as “upper-class” pets. Three centuries later, medical researchers started to use them as laboratory animals for study, and now, guinea pigs can be found almost anywhere in the world. Because of this, guinea pigs make an excellent tool for understanding human history and our relationship with domesticated animals.

Guinea pig

Adriana L. Romero-Olivares

In a recent study, scientists looked at ancient DNA from guinea pig specimens recovered from archaeological sites in Latin America, the Caribbean, Europe, and the United States. They found that guinea pigs left South America, and into the Caribbean, around the 6th century, through existing human networks and trade routes. The work provides some of the earliest evidence of guinea pig domestication and distribution, over thousands of years ago and across long-distance continents far before Europeans arrived in the Americas.

The idea that they’re low maintenance “starter pets” is a huge misconception. They are charismatic, have their own personalities, are extremely vocal and social, eat a lot, poop a lot, and need to be cleaned a lot. But as a guinea pig pet owner, my life has been brightened by guinea pigs for over 15 years. I plan to have guinea pig pets until the day I die. And in doing so, perpetuating a strong bond and evolutionary history dating back thousands of years. Thank you guinea pigs, for teaching us so much.

Scientists' new trick for tracking bacterial infections makes cell walls glow

This technique allows doctors to tell the difference between two different kinds of inflammation

NIH via Flickr

When you experience a bacterial infection, knowing the site of infection helps doctors determine a treatment regimen. Today, clinicians figure out where these pathogens are using radiotracers – compounds with radioactive atoms that react to the X-rays and magnetic field employed by CT and MRI imaging technology. However, clinicians using these radiotracers, such as those that have radioactive fluorine (18F) or gallium citrate (88Ga), suffer from a distinction problem: they cannot distinguish live infections versus a pathogen-free inflammatory response.

Scientists at the University of California, San Francisco came up with a clever solution: synthesize a radiotracer from the building blocks of bacterial cell walls. That way, as the bacteria grow and replicate at the infection site, each live cell is incorporated with a glowing radiotracer. They proved that their radioactive carbon (11C) radiotracer integrated nicely into the bacterial cell wall in the top pathogenic bacteria for hospital settings, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphlococcus aureus — including MRSA.

But if you have an infection in your intestines, where your normal microflora live, will the radiotracer be taken up and incorporated into their cell walls rather than the pathogenic invaders? The researchers answered this question by comparing the radiotracer's location in various organs in normal mice (with normal microbiome) and microbe-free mice. They found that when the radiotracer integrated into the intestines, overall radiotracer incorporation was low, and the difference between microbe-containing and microbe-free organs was minimal. Notably, these 11C amino acids showed significant differences between live cells and dead cells, allowing clinicians to distinguish between live infection sites and sites of inflammatory responses.

Overall, the ease of creating these compounds and great incorporation efficacy into invading pathogens points to an easy translation of this radiotracer from the academic to clinical setting.

Herbivore teeth deep in a South African cave give clues to what the climate was like thousands of years ago

Scientists used carbon and oxygen isotopes to reconstruct past rainfall patterns

Andrew Hall on Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0)

The Nelson Bay Cave, near the coast of South Africa, was excavated between the 1960s and the 1970s. It contains Stone Age remains and is also an important site to uncover past climate fluctuations, thanks to the traces of past animals (such as shells and teeth) the archaeologists found inside.

Between twenty-three and twelve thousand years ago, the cave was not facing the ocean, as it does today. During this period, known as the Last Glacial Maximum, sea level was 120 meters below what it is now, and the cave was facing the vast grassland now known as the Agulhas Plains. There are a lot of unknowns about what happened between that time and the beginning of the Holocene, when the ocean rose and submerged the Agulhas Plains.

To study these climatic changes, a team of scientists from the University of Cape Town, the Natural History Museum of Utah, and Nelson Mandela University studied the remains of herbivorous animals, related to cattle, found in the cave to look for changes in their diet. When an animal eats, some of its body tissues record the chemical signatures of food it has eaten. Scientists can measure this with isotopes, which are slightly altered versions of standard chemical elements. By measuring carbon and oxygen isotopes in herbivore teeth, the scientists could understand how the environment the food grew in changed over time. They identified a shift in the vegetation available at that time, which seems to have been caused by a change in rainfall patterns. This finding is another piece the puzzle of what climate around the world was like during the Last Glacial Maximum.

To understand SARS-CoV-2, scientists found its wild cousins

The original host of this virus is still in question, but studying similar viruses can help us figure out how it evolved

SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus virus responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic, has infected over 9 million people globally and accounted for nearly 500,000 deaths as of June 23. This has led to a global effort whereby researchers have mobilized their labs to better understand the virus.

However, the exact source of the virus has still not been determined. To understand the origin of the virus causing the COVID-19 pandemic, researchers are screening the environment for all types of coronaviruses, such as those found in bats. These efforts will allow researchers the ability to map out the start of the virus' spread.

To further study coronaviruses in circulation, a group of scientists used samples from 227 bats in the Yunnan Province in southern China. The individual samples were collected between May - October 2019. Researchers next determined the viral strains in the samples and discovered two unique coronaviruses called RmYN01 and RmYN02.

Upon further examination, it was determined that RmYN02’s DNA sequence was very similar to SARS-CoV-2. However, there were significant differences in regions the virus uses to enter human cells. Looking closer, researchers noted the RmYN02 virus had only one of six critical anchors SARS-CoV-2 uses to enter human cells. These results were surprising considering the overall DNA similarity.

However, the DNA sequence of the RmYN02 virus did reveal unique mutations thought to be only found in SARS-CoV-2. This points researchers to the fact that this is a close relative of SARS-CoV-2. The origin of SARS-CoV-2 is still the subject of much debate, and it will be difficult to prove with certainty how it jumped from its host to humans. In the meantime, scientists are gathering data on other coronaviruses in an effort to prevent future pandemics.

Methamphetamine can ferry other drugs across the blood-brain barrier

Giving rats small doses of meth along with cancer drugs increased transfer of the cancer-targeting medicine into the brain

Antonino Paolo Di Giovanna on Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0)

The brain is a champion of self isolation. In other parts of your body, drugs and nutrients enter through the lining of blood vessels. While the brain is full of blood vessels, specialized vessel walls tightly regulate what can get in. This “blood-brain barrier” is important for protecting the specialized environment of the brain, but it is also a problem when trying to treat conditions like brain cancer or neurodegeneration as drugs can't get in.

We do know of some drugs that are really good at getting through this barrier, either by slipping in or by breaking the barrier down. A new study, currently published as a pre-print, has found that giving rats a drug that easily crosses the blood-brain barrier helps other drugs get into the brain, even if they aren’t normally able to.

What is this barrier breaking drug? Methamphetamine, also known as meth. Meth’s powerful effects are partly due to its ability to get into your brain. At low doses, it can increase a process called fluid phase transcytosis, in which a drug is packaged and transported into the brain by the cells lining blood vessels. While previous studies have shown this is how low dose meth enters the brain, this new study is the first time it’s been shown that it can bring other drugs along for the ride.

Researchers gave low doses of meth to rats, along with therapeutic drugs that don't easily cross the blood brain barrier. They then looked at the rats' brains to see what molecules were present. The therapeutic drugs got into the brain far more easily if meth was given at the same time. In another experiment, meth was able to help a chemotherapy drug enter the brain, which increased survival in a mouse model of brain cancer.

Meth isn’t often associated with medicine, but it is FDA approved for some uses. In cases such as aggressive brain tumors, it may be worth using a little meth for a lot of chemotherapeutic.

A bacterium that causes food-borne illness grows flagella under stressful conditions

Escheria albertii, a cousin of E. coli, has been implicated in past food-borne illness outbreaks

Micro-organisms, especially bacteria, play essential roles in our bodies, especially in our guts. Some bacteria are beneficial, and some like E.coli are harmful. Another Escherichia strain (in the same genus as E. coli) named Escherichia albertii is also pathogenic to humans, causing diarrhea and food-borne illnesses. E. albertii was identified for the first time during an illness outbreak in Bangladesh.

Pathogenic bacteria like E. albertii are very motile, meaning they move around a lot. They are able to do this using hair-like structures called flagella. E. albertii was originally described as non-hairy bacterium and thus far has been considered to be a non-motile pathogenic micro-organism.

A new study led by Tetsuya Ikeda and a team at Hokkaido Institute of Public Health in Japan has found that this may not be true: stressful environments can stimulate E. albertii to make flagella. They showed that, despite the fact of having most of the genes needed for flagella, at normal temperature of 37 degrees Celsius this bacterial strain does not show any motility. But in conditions such as low salt and nutrient concentrations and colder temperatures (20 degrees C), the bacterium's flagellar genes are activated and it becomes motile. More motile cells can survival better under unfavorable conditions, making them more harmful to humans.

Viruses exploit marine bacteria for energy

These minuscule interactions could have ripple effects on global carbon dioxide levels

Viruses that cause devastating pandemics are not exclusive to humans. Prochlorococcus marinus, a marine photosynthetic bacterium, is infected by many viruses – and this ecological interaction has consequences for all of us.

As the most abundant photosynthetic organism on Earth, P. marinus has a vital role in our ecosystem. Collectively, these bacteria absorb about four gigatons (four billion metric tons) of carbon dioxide every year via photosynthesis.

In a newly published paper, researchers at Rice University in Houston studied how bacteriophages, or viruses that infect bacteria, affect photosynthesis in P. marinus. They were particularly interested in ferredoxin proteins, which are involved in transporting the electrons harvested from light during photosynthesis. The ferredoxin proteins of bacteriophages that infect P. marinus were very similar to the proteins of the bacteria themselves that are involved in taking up nutrients. Much like putting a cable to a car battery and using its energy to cook dinner, phages redirect the electrons harvested by the bacteria for their own purposes.

By redirecting light energy to be used in incorporating nutrients instead of storing carbon, phages can offset the abilities of P. marinus to remove carbon dioxide from the air. Thus future studies on the spread of these viruses and how they might change in warming temperatures might be crucial in our projections of climate change.

Wood avens flower fashionably late to avoid beetle attacks

But that comes at a cost to seed production

Anyone who’s been punctual to a party knows that the first hour is pretty awkward. Some of us even prefer to arrive fashionably late to social events, so we won’t have to endure too much awkward silence until the energy builds up.

New research published in the Journal of Ecology suggests that tardiness can help plants avoid unpleasant situations too. Wood avens are forest herbs that reproduce by seeds. Early summer blooms produce the best seeds. Unfortunately, this is also when fruitworm beetle larvae hatch and feast on the developing seeds.

.png)

Udo Schmidt on Wikimedia Commons

One way that the flowers can avoid beetle breeding season, ensuring that more of their own offspring survive, is by blooming later in the summer. By tracking wild plants, scientists found that those attacked by beetles in early summer did not compensate for their losses by producing more flowers later that year. Instead, the plants revealed their coping strategy in the following year, when they delayed flowering to avoid being attacked again.

But blooming late comes at a cost. The forest canopy grows dense in late summer, shading the wood avens. Without sufficient light, late bloomers make fewer seeds than beetle-free early bloomers. Blooming early is thus advantageous in places or periods where beetles are relatively few. This trade-off to blooming early or late may be why wood avens have evolved flexibility in their flowering time.

This study is the first to show a plant biding time to avoid negative situations, as a direct response to past experiences. Can other plant species do this too? Science continues to uncover the plant kingdom’s diverse, and often unexpected, defense strategies.

Disentangling gene interactions in nematodes helps us learn about human cancer

New research highlights genes that control cell division, and others that invade nearby tissues

The basement membrane is a thin layer of cells and molecules that divides internal or external body surfaces (like your skin or blood vessels) from connective tissue. Basement membrane invasion is when a cell “invades” or moves across neighboring tissues, and it happens a lot in cancers. While many discoveries about how this process plays a role in cancer have been made in mice and human cells, these studies can take a long time. The nematode Caenorhabditis elegans (C. elegans) is a great alternative because it can quickly reproduce and actually uses basement membrane invasion to make its vulva.

Previous work has found that four genes are needed for basement membrane invasion in C. elegans. However, until now it wasn’t clear how these four genes interacted with each other. A recent study, published in the journal Development, discovered that these genes work in a specific cell called the anchor cell (AC) prior to invasion to regulate its division. The AC is a good cell to study because, in C. elegans, it must invade the vulval cells to form a bridge between the uterus and the nematode's vulva. If the AC does not do this, the nematode can't lay eggs.

When the four genes were individually turned off in healthy worms, instead of having one AC that could invade, they had many ACs that couldn’t invade the basement membrane, suggesting that turning off the genes prevents the AC from stopping itself from dividing. The researchers wondered if these mutations could be fixed by adding a protein called CKI-1, which is required to control cell division. Adding CKI-1 into the AC solved the problem when some combinations of the four genes were switched off, but not others, a hint that those other genes might perform different functions. But they work together to help the AC invade the vulval cells, a process which mirrors the way cancer cells invade other parts of the body.

Although these findings may sound incredibly specific and complex (and they are!), because the genomes of C. elegans are so similar to ours, they provide a roadmap for finding human genes that may be involved in cancer.

Measuring how quickly proteins accumulate in the brain could help scientists identify people with Alzheimer's disease faster

Faster diagnosis means quicker treatment of this currently incurable disease

NIH Image Gallery / flickr

Biomarkers are quantifiable indicators of illnesses (such as levels of certain proteins in blood) that may otherwise be difficult to diagnose. Researchers are actively searching for biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Current approaches focus on designating people as “positive” or “negative” for AD based on the amount of two proteins, amyloid-beta (Aβ) and phosphorylated tau (p-tau), in their brains. Patients with more Aβ and p-tau than a certain threshold are considered positive, indicating that they are likely to develop AD.

But more and more, clinicians are discovering exceptions to this yes/no designation system. For example, there have been many cases of those with significant Aβ plaque formation who remain “cognitively intact”, meaning they don't develop dementia or other symptoms of AD, throughout their lives. These exceptions highlight a disconnect between the total accumulation of these biomarkers and the impact on cognitioon.

Scientists have challenged this static system in a new paper, published in a specialized journal for AD research, by introducing time-inclusive categories. Instead of focusing on protein levels, they categorized individuals by how rapidly their brains accumulated Aβ and p-tau. To demonstrate the utility of their system, the researchers analyzed a group of 250+ cognitively normal individuals to see if they could identify the Aβ and p-tau biomarker accumulation rate and their association with AD risk factors, like the APOE4 allele. Their system successfully separated volunteers into distinct groups for both biomarkers. They could also identify timepoints of “escalating accumulation” within each group.

This system provides greater context for at-risk individuals and opens the door for earlier treatment of AD in people who were not considered positive for AD under previously used biomarkers. As more research points to the spread of the “amyloid burden” much earlier in life than the onset of cognitive decline, this new categorization can create more realistic diagnosis timelines for the currently incurable disease. To draw their final conclusions on the efficacy of their system, these researchers must continue monitoring study participants to determine when and if they develop AD. In its current state, their system is an untested theory beholden to the same master as those potentially afflicted with AD: time.

Bone proteins can help identify how long a body has been submerged in water

This finding will help forensic teams better determine time of death in some cases

Photo by Meta Zahren on Unsplash

One of the most important tasks for forensic scientists after a body is found is to determine the exact time of death. This is key in piecing together the events that led up the death and is especially important when a crime is suspected. The typical signs of post-mortem change in human bodies are often extremely hard to read if a body has been submerged in water, making it even harder to determine the time of death.

New research from a team at Northumbria University, UK, has revealed a new method to calculate time of death of a body found in water, based on proteins found in bones. The team found that several common bone proteins underwent a chemical change called deamidation when a corpse was submerged in water. More importantly, they found that the longer a corpse was submerged in water, the more deamidation was taking place. They also showed that some types of water, such as pondwater, had a noticeably different impact on protein deamidation in bone after death.

These studies were performed in mice, and obviously must be replicated using human cadavers before the findings are translated into forensic practice. But they have identified some very promising biomarkers for determination of how long bodies have been submerged in water, and their chemical method can be replicated in other labs.

Cold-sensing neurons help tell animals when to hibernate

This brings new insight into how mammals and birds survive frigid winters

Photo by Chris Geirman on Unsplash

Imagine you live in Canada and it is December. The cold has started to creep in. It takes layers of warm clothes and central heating to keep you from shivering. You look outside the window, see birds fluttering around and think to yourself, “How do animals survive out there?”

Many mammals (like rodents and bears) and birds (like hummingbirds) have the amazing ability to undergo ‘torpor’, during which they slow down their bodily functions to conserve energy. Animals make use of this to survive harsh environmental conditions. However, the mechanism by which animals sense the surrounding temperature and exhibit such a response is not known.

Researchers from Yale University explored this in a recent study published in eLife. They describe how a group of cells called POA neurons in the hypothalamus region of the mouse brain sense cold and get activated to relay the signal forward.

To understand what sets POA neurons apart from other cells, the scientists looked at the different components they are composed of. All neurons receive information with the help of small pores on their surface, which open only when their partner molecule sticks to them. What makes POA neurons special is the abundance of one such pore, which becomes increasingly likely to open as temperatures drop and it becomes more attracted to its partner. Once open, it allows the neuron to become active and pass on the message. The property of the pore to unlock for low concentrations of the partner molecule at cold, but not warm temperatures, is what makes it a cold sensor.

Findings from this study shed light on one possible mechanism of cold temperature sensing. But in order to fully understand how animals survive frigid conditions, we still need to tease apart the steps from sensing temperature to regulating it.

Bumble bees cut holes in plants' leaves to trigger flowering

This remarkable behavior was discovered during routine observations of bee behavior

Jubair1985 on Wikimedia Commons

For anyone who recently celebrated World Bee Day, it should come as no surprise that these amazing animals are being studied for yet another mysterious and complex behavior. This new behavior, however, stands out not only for its novelty, but also for its important implications for the future of insect pollinators.

Due to climate change, many plants and animals have shifted their annual timing of reproductive and developmental milestones, such as the production of flowers in plants. Mutualistic relationships, including those between pollinators and plants, are in danger of breaking down unless these shifts can be coordinated across species.

Researchers at ETH Zurich in Switzerland noticed that bumble bees cut holes in the leaves of their host plants, and they wondered if this behavior could be a mechanism for triggering earlier flowering, thus syncing up flower production to the bumble bees’ needs. The researchers performed a series of experiments in which they gave bumble bees access to plants and recorded both the bee behavior and the plant flowering dates. They found that bees most often made the characteristic cuts in the leaves of plants that lacked flowers, and they were more likely to make these cuts if they were hungry rather than well-fed. Furthermore, plants that had their leaves cut by bees started flowering earlier than those that were left undamaged.

These results, which were recently published in Science, imply that bumble bees use this unique leaf-cutting behavior to induce earlier flowering in the plants they pollinate, and thus gain access to critical food resources when they need them. The mechanism underlying the early flowering response in the plants is unknown, but it may be beneficial if it allows plants to maximize pollination through optimal timing of flower production.

While it is unclear how widespread this behavior is, it poses exciting new explanations for how pollinators and flowering plants synchronize their life cycles, which may be critical for their survival in our rapidly changing climate.

Overactive neurons may explain why some people develop stress-induced anxiety and depression

The research also points to sex differences in how male and female mice respond to stressful events

Image by MethoxyRoxy, reproduced under CC BY-SA 2.5

Stress is a known risk factor for a number of psychiatric disorders including anxiety and depression. Yet, not everyone who experiences stress develops these disorders. A study by a group of scientists at McGill University in Canada has revealed that the activity of a specific group of cells in the brain, neurons projecting from the ventral hippocampus to the nucleus accumbens, may be able to predict one’s susceptibility to develop stress-induced anxiety and depression.

First, the scientists observed the activity of these neurons in stress-free mice. They found that the cells were more active in naturally anxious mice. They also found increased neuron activity when non-anxious mice socially interacted with a stranger mouse.

They were able to link enhanced neuron activity to stress vulnerability (and increased anxiety behaviors) in female mice. Although the link was only predictive for the behaviors in female mice (which is interesting in itself as females have been shown to be more prone to these disorders), both sexes undergo the same increase in neuronal activity once exposed to stress.

As such, it appears that these neurons may be used as an indicator to predict one’s susceptibility to stress-induced psychiatric disorders. This may pave the way to for future targeted treatments and prevention strategies.

Lizards beat the heat by finding new "microhabitats"

The behavioral change offers refuge from large temperature swings

Reptiles living at very high elevations have already adapted to some extreme conditions, including low oxygen levels and cold air temperatures. Scientists are now concerned that some Andean reptiles may not be able to handle the latest threat: overheating.

The Andes mountains of South America host a diverse array of plant and animal life which is becoming increasingly threatened by climate change. Reptiles are especially at risk because they are cold-blooded, so their internal body temperatures changes with external temperatures.

Stenocercus trachycephalus

To understand how some reptiles may respond to this pressure, a team of Ecuadorian scientists headed to the mountains to study two high elevation species of lizards, Stenocercus guentheri and Stenocercus festae. The team first recorded the lizards’ body temperatures in their natural forest habitats. They then took the lizards back to the lab to see how well these species tolerate temperatures outside of their comfort zones.

The results, published in PLoS One in January, show that these Stenocercus lizards can change their behavior to endure temperatures beyond their preferred ranges, taking advantage of “microhabitats” that offer shelter from extreme temperature swings in the broader area. Such microhabitats may become increasingly important as other reptiles find ways to adapt to rising temperatures.

The case of three drugs repurposed for trials to treat COVID-19

Confused about which drugs do or don't work?

COVID-19 is currently affecting more than 8 million people worldwide. While the spread has been contained in some countries, the lack of an actual treatment puts many patients at risk of death and long-term injury. Although infected people can develop antibodies and overcome this disease, many young and old are not able to fight back.

Since developing an effective drug can take several years, scientists have been looking at drugs currently in the market that could be repurpose to treat COVID-19 patients. Are there any that have been successful or at least show potential?

The answer is yes and no. In only a week, three drugs put forward for the treatment of the novel coronavirus have changed paths. The first one, hydroxychloroquine, is an antimalarial drug. Once authorized for emergency use by the FDA, this drug is been now revoked as a treatment for COVID-19. The FDA has said that there is no evidence that ensures that oral administration of hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine may be effective in treating the disease. On the other hand there is evidence that it could instead pose heart risks for some patients.

The second is remdesivir, an antiviral drug. This drug, currently approved for emergency use by FDA, has shown only moderate potency with no statistically significant effect on deaths. However, detailed studies have revealed a very specific mechanism of action by blocking the viral machinery in charge of its replication. Gilead Sciences, the company who makes this drug, is looking at ways to make this drug viable to be inhaled as a powder or injected subcutaneously. Remdesivir is currently administered intravenously as it cannot be degraded in the liver.

Lastly, as of June 16, dexamethasone, a steroidal drug, has shown to save lives of severely ill patients. This widely available and cheap drug was the only one in a pool of five treatments included in the RECOVERY trial that show a statistical decrease the number of deaths in one of the world’s biggest randomized trials. This new finding is considered a breakthrough and offers some hope as this medicine is widely available in pharmaceutical shelves worldwide.

Astronomers just solved the Universe’s missing mass mystery

They used bursts of radio waves to weigh, well...everything

Wikimedia

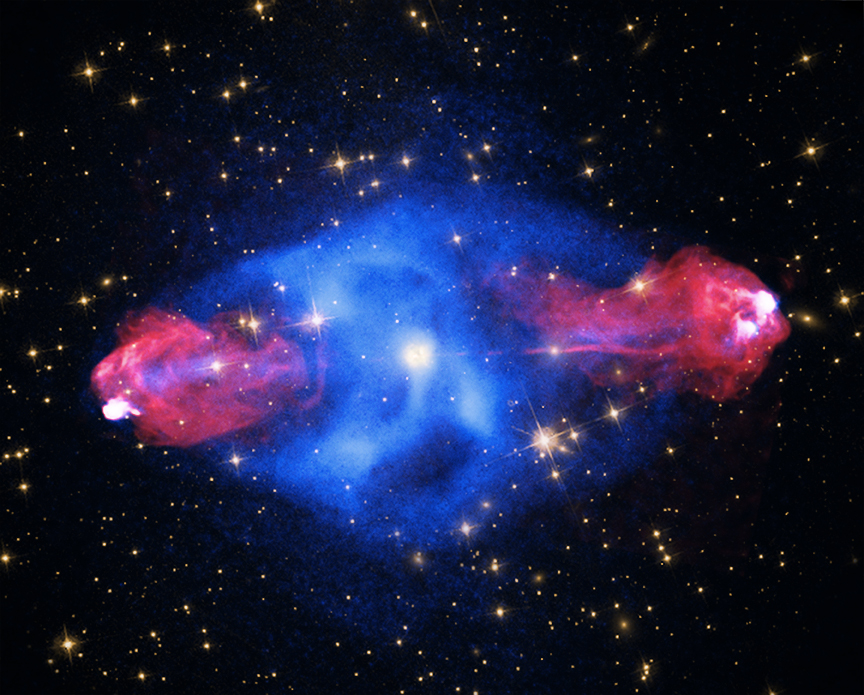

For decades, astronomers have pondered over the mystery of why up to half of the ordinary matter in the Universe was missing. Cosmologists predicted that this ordinary, or "bariyonic" matter should make up five percent of the Universe, with the rest being dark matter and dark energy. But that prediction failed — they only saw half of this amount when scanning all the stars, galaxies, and ordinary matter throughout the known Universe.

Astronomers have long believed that the Universe’s missing matter is hidden in a low-density plasma between galaxies known as the warm-hot intergalactic medium, or WHIM. But this plasma is really hard to detect.

Cygnus A galaxy

Wikimedia

In a new study published in the journal Nature, a team of astronomers finally found this missing mass with distant radio signals known as fast radio bursts, or FRBs. The amount of matter they detected was exactly consistent with what cosmologists predicted we’d find more than two decades ago.

Soon after FRBs were discovered in 2007, however, astronomers realized their potential as probes of this faint region of the Universe. While we still don’t understand exactly what FRBs are or how they’re emitted, we do know that most of them originate outside of the Milky Way and travel through vast reaches of interstellar space — including the WHIM — to reach telescopes here on Earth.

Radio signals slow down as they pass through matter, with longer radio waves being slowed down more than shorter ones — a phenomenon known as “dispersion.” By measuring the amount of dispersion in a sample of FRBs, the team was able to determine just how much matter there really was hidden away within the WHIM.

It only took 6 FRBs to weigh the Universe, but telescopes around the world are detecting more of these signals every day. Future observations will allow astronomers to map out how subatomic particles are distributed throughout the WHIM, shedding further light on one of the most mysterious regions of the cosmos.

A two degree temperature increase nearly triples pathogens that cause plant disease

The fungal pathogens already cause hundreds of billions of dollars in damage

Soil is a crucial resource for food production. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, an estimated 95% of our food directly or indirectly depends on soils. However, soils are also a reservoir for fungal pathogens. A 2019 analysis found that plant diseases caused by fungal pathogens and other biological threats cause $220 billion of damage every year.

As the planet warms, the prevalence of soil-borne pathogens is expected to increase. A team of researchers wanted to forecast future distributions of these pathogens to aid in understanding how to reduce their impact on food production.

95% of our food directly or indirectly depends on soils

Pixabay

The researchers first produced a model using data describing environmental conditions and relative abundance of various pathogens in various natural ecosystems from around the world. With this, they found that temperature was the factor that caused the largest increase in soil-borne pathogens globally.

The researchers then validated their model’s findings with a nine-year field study in a grassland in Spain. They created open-top chambers that would simulate a warming treatment of 2 degrees Celsius — similar to expected increases in temperature in the area due to global warming. After nine years, they collected soil samples and found that the relative abundance of plant pathogens had nearly tripled.

The results of this study can be used to better understand and predict how human activities and land use will impact food production and the livelihoods of those who depend on it.

Scientists are building a machine to recreate fusion inside of the Sun's core

The first of 18 powerful magnets needed for the machine, called ITER, was just completed

Rswilcox on Wikimedia Commons

Imagine for a second that we could recreate a star on Earth and use it as a clean energy source. How cool would it be to not just harvest the Sun’s power, but to also reproduce it? Well, we are on our way to doing just that.

On April 17th, 2020, after 12 years of collaboration between European countries, the USA, Russia, Japan, India, China, and South Korean, the first of 18 magnets that we need to develop fusion energy was unveiled. These magnets are part of building ITER, an experimental machine for producing the energy.

The goal is to reproduce energy production inside the Sun's core, where two light hydrogen atoms – at very high temperatures – collide and fuse into one helium atom, releasing the energy that supports life on Earth.

Reproducing this on our planet requires the ability to run a reaction at a temperature of 150 million °C, where hydrogen exists in the form of ionized gas (also called plasma). Under these conditions, the plasma is extremely hot and difficult to manage. This is where the magnets come in. They are part of a donut-shaped machine called a tokamak, which can contain the plasma through powerful magnetic fields sustained by enormous magnets. Different prototype tokamaks exist around Europe, but ITER will be the first capable of maintaining the plasma for at least 1000 seconds. This will put its power output on par with traditional coal or oil-powered plants. The plan is that ITER will be ready to generate the first plasma

ITER is being built in the South of France. The machine will be a giant: 24 meters high and 30 meters wide, weighing 30 tons. According to the plan, ITER will generate its First Plasma by the end of 2025.

Squid skin is naturally anti-microbial

This new finding makes squid skin a potentially valuable medical product, and could reduce waste from commercial fisheries

Minette on Wikimedia Commons (CC BY 2.0)

Many types of squid have the ability to alter the color of skin cells called chromatophores, in order to blend in with their environment. This allows them to hide from predators, and is often triggered when the squid feels threatened. These same squids, including the Humboldt squid (Dosidicus gigas), are commercially fished in parts of North and South America.

Now, researchers working in Spain and Mexico have identified the pigments in Humboldt squid chromatophores as ommochromes. Chemical analysis showed that the main violet-coloured ommochrome is a compound called xanthommatin, which the researchers found to have strong anti-microbial properties. Their study showed that xanthommatin could inhibit the growth of several microorganisms that can cause disease in humans, including the fungus Candida albicans (which causes thrush and yeast infections) and bacteria like Salmonella enterica.

Skin from the squid is often discarded as waste from fisheries, but this new research tells us that it could be used to produce valuable medical compounds. The dumping of squid skin as waste "generates pollution problems in the coasts," says study co-author Jesús Enrique Chan in a news release, "so research like this, in which we inform about how these wastes could be used, helps to revalue them."

Humboldt squid aren't the only squid that produces this pigment. The tiny Hawaiian bobtail squid (Euprymna scolopes) also produces the anti-microbial xanthommatin pigment, as do many other species.

A 66 million year old evolutionary experiment created sabre-toothed anchovies

Behold, the mystery of a singular hidden fang

Joschua Knüppe

The most exciting paleontological discoveries aren't always made in the field, dusty and sweaty in the sun. Sometimes, you're still dusty, but the fossils are buried in a cabinet.

When doctoral student Alessio Capobianco and his advisor, Matt Friedman, were digging through a cabinet of fish fossils, they weren't sure what to expect. Collected in the 1970s from Pakistan and never described, the fossils comprised little-studied fish from about 66 to 40 million years ago.

One of these fossils stood out: a 10 centimeter long portion of a fish's head — an extinct ancestor of anchovies — with a handful of large fangs sticking out of its lower jaw. Intrigued, Capobianco and Friedman put the fossil through a CT scanner to map its internal structure.

The scan revealed a single "sabre-tooth" fang jutting out of the fish's upper jaw. "When I saw that, I was equally surprised and excited," Capobianco says. "We knew we had something remarkable in our hands."

Why did the fang stand out?

Most anchovies today feed on tiny organisms called plankton, so they don't need big teeth, let alone fangs capable of ripping other fish to shreds. That raises an evolutionary question: which came first, the fish-eaters or the plankton-eaters? Either is possible, given that this anchovy evolved in the chaotic wake of a mass extinction 66 million years ago. In this time, Capobianco says, "Bizarre 'evolutionary experiments' occurred, but not all of them made it to the modern day. Sabre-toothed anchovies are a perfect example of such failed evolutionary experiments."

Wikimedia

That single sabre-tooth also stands out among fossils because other fish lineages, such as eels and anglerfish, have fangs — plural. Capobianco's fossil has just one and he, excited to name his first species, thought carefully about what call their discovery. He settled on Monosmilus, meaning "single knife."

The fossil Monosmilus answers some of the questions about fish evolution between 66 million years ago and today, but it raises others. More fish fossils — and maybe more dusty cabinets — will be needed to solve those puzzles.

Color-changing band-aids show when patients are infected with superbugs

These “sense-and-treat” bandages change color when in contact with antibiotic-resistant bacteria, and then eliminate them

Antibiotic resistance in bacteria may rise due to increased usage of hand sanitizers and antibacterial-containing soaps brought on by Covid-19. Identifying an antibiotic-resistant strain of bacteria is necessary before it can be effectively treated, but this requires additional testing that can be lengthy and costly. Scientists at the University of Science and Technology in China got around this by designing smart band-aids that change color upon contact with antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

The scientists integrated a chemical structure called a metal organic framework (MOF) onto their band-aid and loaded it with various color chemicals. The pH of your skin decreases during a bacterial infection, and they included a chemical called bromophenol blue, that turns from blue to yellow in more acidic environments.

To detect antibiotic resistant bacteria, the scientists took advantage of an enzyme they produce called β-lactamase. This enzyme breaks down common antibiotics like penicillin. It also breaks down the second chemical loaded into the bandage, called nitrocefin. When that happens, the color of the nitrocefin changes from yellow to red. So, the band-aids that these scientists designed turn red when they are covering a wound with an antibiotic-resistant bacterial infection, yellow if atop normal, antibiotic-sensitive bacteria, and stay colorless on infection-free wounds.

To treat the infection, the scientists took advantage of non-antibiotic therapies such as UV radiation and reactive oxygen species. UV light causes DNA damage in bacterial cells. Because of the design of the bandage's metal-organic framework, UV light shined on the band-aid also creates special oxygen molecules called reactive oxygen species (you may have heard of these as justification for eating antioxidant-rich foods). These reactive oxygen species poke holes in bacterial membranes.

The researchers demonstrated the effectiveness of the band-aids by applying them to E.coli-infected wounds on mice. In just a few days, the band-aids turned yellow or red (in case of drug-resistant E. coli), UV radiation killed the infection, and the wound healed. As the relative cost of making these smart band-aids is low, large-scale production and clinical application of this exciting innovation could be implemented quickly.

T cells could be the key in developing an effective COVID-19 vaccine

Our bodies have two main types of T cells. Together they can help us fend off this virus

Photo by Glen Carrie on Unsplash

Many have embraced antibodies and the possibility of immunity to COVID-19 as the key to reopening society and the economy. Serology testing – also known as antibody testing – can indicate whether someone is producing an immune response to the virus.

But we still do not know whether the presence of antibodies in recovered patients holds promise for long-lasting immunity. Insight from immunological studies on recovered SARS patients infected in 2003 showed that antibody levels wane after just a few years. A different immune response caused by T cells provides long term protection, even 11 years post-infection.

Based on this data, it is likely that T cell responses play a substantial role in developing protective immunity against SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. There are two main types of T cells: helper and killer T cells. When they recognize a virus, helper T cells signal to activate other types of immune cells, while killer T cells release molecules that destroy the virus.

In a new study published in the journal Cell, researchers at the La Jolla Institute for Immunology identified viral protein pieces in SARS-CoV-2 that are already known to induce T cell immune responses. They then exposed the immune cells from ten recovered COVID-19 patients to these protein pieces and measured the T cell immune responses.

All of the patients had helper T cells that recognized the main SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, and about 70% of them also had killer T cells that recognized the spike and membrane proteins. The main target of the 100+ vaccines for COVID-19 in development is the antibody response to the spike protein, but this new understanding of the T cell response could provide new and potentially better targets.

The mission to make a vaccine against COVID-19 is possibly the most urgent public health problem in the world today. The encouraging results in both the similarities in immune response to SARS and SARS-CoV-2 and the identification of strong T cell responses in recovered COVID-19 patients promote further research in designing vaccines to induce T cell responses.

The Trump administration puts transphobic pseudoscience into law

They call it science but it's nothing of the sort

The Trump administration has removed healthcare discrimination protections from trans, intersex, and non-binary people. They did this by rewriting what defines sex under an Obama-era rule on how Title IX protections were interpreted, as they applied to the Affordable Care Act. The Obama interpretation allowed for "neither [male nor female]" or "a combination of male and female" as protected classes. The key sentence in the new rule:

"HHS [Health and Human Services] will enforce Section 1557 by returning to the government’s interpretation of sex discrimination according to the plain meaning of the word “sex” as male or female and as determined by biology."

This is bullshit. Biology has time, and time, and time again shown that sex is not one of two options, but an entire three-dimensional spectrum.

This new rule simply allows, among other things, health providers to deny trans people healthcare, no matter how vital. If a trans man with, say, uterine cancer sought treatment, he could be denied for no reason.

What sex is is very clear-cut. It's like arguing about the color of the sky. The arguing is also pointless: a trans person does not need to justify who they are, with science or without it. The Trump administration is using "biology" as a costume to beautify its hate. Any future administrations must put LGBTQIA+ protections into written law and not have those protections sit out at the sneering whims of bigots.

Today is June 12th, the four year anniversary of the Pulse nightclub shooting.