Tolu Bamwo/Nappy.co

Racial injustice causes Black Americans to age faster than whites

The "weathering hypothesis" explains higher rates of chronic disease and infant mortality

Nelson Scott* presented to the emergency room on his thirty-second birthday. A tall Black man with an athletic build and a clean fade haircut, he had the manners and the accent of someone raised in the South. He had recently graduated from law school in Texas and was on vacation in Los Angeles to celebrate. On the second morning of his trip, he woke up in his hotel room with stabbing abdominal pain and relentless vomiting. He wasn’t able to keep even sips of water down.

In the emergency room, I ordered a CT scan of his abdomen. The results were surprising: there was nothing to explain his symptoms. All the organs that usually cause abdominal pain — the liver, spleen, kidneys, intestines — appeared normal. What surprised me were the findings doctors call “incidental” — the conditions that we diagnose unintentionally, typically on scans we ordered to look at something else entirely. Nelson’s incidental findings were astounding.

He had arthritis up and down his spine, and the fluid-filled disks between the vertebrae were worn down. His aorta contained patchy calcifications — a hallmark of atherosclerosis. Arthritis and atherosclerosis are almost unheard of in a 32-year old with an otherwise unremarkable medical history. Nelson had the body of someone almost twenty years his senior.

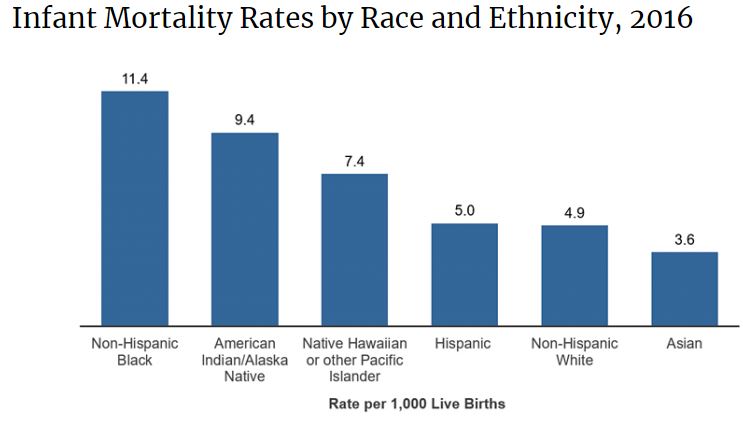

Decades ago, psychologist Arline Geronimus noticed something similar in a cluster of young Black women she worked with while studying teen pregnancy at Princeton University. The women seemed to have pregnancy-related complications usually seen in much older women. In a study she published in 1991, Geronimus examined infant mortality by maternal age across different racial groups. She noted that in white women, the highest mortality rates occurred in teen mothers, and declined as women reached their 20s. But in Black women, the opposite happened.

Not only did Black infants have higher mortality than white infants in every maternal age group, but infant mortality was lowest in teenagers, and steadily rose throughout the remainder of the childbearing years. Even during the “prime” childbearing years of the early 20s, mortality rates climbed. This ran counter to conventional wisdom, which held that teen pregnancy was less healthy and that there was a “sweet spot” for childbearing in the third decade of life. The rule didn't seem to apply to Black women. Their infant mortality rates started out worse than white women, and the gap only widened from there. Geronimus wondered if Black women never had a “sweet spot” because they started aging earlier and faster than white women.

She was not the first to call attention to stark differences in disease prevalence between racial groups. Over the past few decades, dozens of studies have found inequalities across a broad range of diseases. Black Americans are more likely to die from coronary heart disease than any other racial group in the United States, and are four times more likely to develop end-stage kidney disease than white Americans. Though breast cancer is diagnosed less frequently in Black women, those who develop the disease are more likely to die from it. Cervical cancer is more common and more deadly in Black women compared to white women. Examine almost any chronic disease, and you’ll find that Black Americans are more likely than white Americans to have it. Black Americans, simply put, get sicker and die younger than white Americans.

Black Americans are more likely to die from coronary heart disease than any other racial group in the United States.

Many of these racial health disparities can be accounted for by substandard healthcare for the Black community. A pair of studies published in the early 2000s found that across a broad spectrum of health care services — from cancer screening to eye exams to routine office visits after hospitalization — Black Americans received less and lower-quality care. In explaining this, public health researchers have often pointed to a simple lack of healthcare coverage, citing studies that show Black individuals are less likely than white individuals to have health insurance. Economic forces are also partially responsible: Black families have a lower median income and are more likely to live below the poverty line than white families, which, in the context of rising healthcare costs, forces many people to forego some testing and treatment.

More insidious forces are also at play. Implicit bias — associations outside of conscious awareness that lead to negative evaluations of people of color — is prevalent among healthcare workers. Studies have shown that when treating Black patients, doctors are less likely to offer cardiac catheterization, make referrals for kidney transplant, or even prescribe cholesterol medication.

But none of this can quite explain Geronimus’s finding that infant mortality got higher as women matured into early adulthood, when white women's infants appeared healthier. It cannot explain why, according to a 2017 CDC report, a Black woman with an advanced degree is still more likely to lose her baby than a white woman with an eighth grade education. Nor can it explain why Scott, an otherwise healthy, educated man with health insurance, had arthritis and atherosclerosis at only 32 years old.

Geroninmus proposed an answer. Systemic racism, she said, directly affects the health of marginalized communities, and may be to blame for the early health deterioration seen in so many Black Americans. According to what she termed the “weathering” hypothesis, Black people in the US experience premature aging and its attendant health conditions because of the cumulative, repeated impact of social, economic, and political inequality. In a race-conscious society, Black individuals face frequent stigma and marginalization, producing near-constant level of stress that can become physically toxic.

The human body has an intricately orchestrated response to a perceived threat, whether it is a confrontation with a bear, the prospect of public speaking, or, for a Black man, the experience of being followed by a police car because of the color of his skin. A surge in stress-related neurotransmitters, called catecholamines, leads to the secretion of corticotropin, which in turn triggers the release of cortisol, the body’s prime stress hormone. It’s the classic “fight or flight” response.

After the bear has moved on, the speech has been given, or the police car has disappeared, the cascade is inactivated, and levels of catecholamines and cortisol return to baseline levels. But if the threat is frequent, the body doesn’t have a chance to fully deactivate. Black Americans' lives are peppered with stress-inducing events, ranging from acts of blatant racism to simply bearing the constant burden of being judged as representatives of their race. High levels of stress hormones linger in the body, exerting damage, on a cellular level, to the cardiovascular, metabolic, and immune systems. Over weeks, months, and years, “fight or flight” turns into “wear and tear.”

In the scientific community, this wear and tear is called “allostatic load.” One way to measure allostatic load is by examining the substances the body releases in response to stress — catecholamines and cortisol, for example. The second is by measuring the effects of these substances on health metrics like blood pressure and cholesterol. Both categories can be combined to calculate an allostatic load score. The score reflects the extent of the cumulative physiologic stress a person has encountered, a rough proxy for how much aging they’ve experienced. It’s a way to quantify weathering.

In a 2006 study, researchers used questionnaires, blood tests, and government data to calculate allostatic load scores for a group of Black and white men and women. Black study participants of both genders scored significantly higher than white participants, even after making adjustments for income level. In fact, middle-class Blacks had a greater probability of a high score than whites living in poverty. In each age group, the mean score for blacks was roughly comparable to that of whites who were a full 10 years older. It was some of the first quantifiable proof that Black Americans are indeed aging faster than their white counterparts.

Dozens of subsequent studies have shown that weathering has played a role in racial inequities in obstetrical outcomes, such as pre-term birth and low birth weight, as well as hypertension, diabetes, stroke, cardiovascular disease, and even longevity. One study examined telomere length, which has been shown to approximate biological age, in groups of black and white women. Black women had significantly shorter telomeres than white women, corresponding to an older biological age by roughly 7.5 years. Another study found that evidence of weathering is detectable as early as childhood. In these studies, the findings persist even after accounting for factors like education, income, and access to healthcare, meaning that having a college degree, financial security, and health insurance cannot provide immunity against weathering.

In Nelson Scott’s CT report, the radiologist offered a comment on his atherosclerosis and arthritis, stating that the findings were “unusual in a patient of this age.” On the other hand, maybe the early degradation of his body wasn’t unusual at all. In his 32 years, he experienced weathering every time a woman clutched her purse as he walked by, a clerk trailed him throughout a store, or he was stopped without reason by the police. No level of education or economic advantage could insulate him from interpersonal or institutional racism. His body experienced racism as a threat; over the years, it took its toll.

*Ed. note: The author, a medical doctor, has omitted any identifying information and used a pseudonym, in accordance with HIPAA guidelines.

I really enjoyed reading your article; it was captivating and informative. The studies you cited, in combination with your interpretation, do an excellent job of exposing systemic racism’s effects on health. It’s truly sobering.

I’m an analytical chemist and I use mass spectrometry to better understand racial disparities on a molecular level in sepsis. I’ve read studies that show individuals of African and European descent have different immune responses and that disparities in sepsis exist even after accounting for socioeconomic variables. Additionally, clinical trials and research studies (which, historically, have harmed countless Black lives) are done primarily on white populations today. So I think a possible component of why racial disparities exist is that no one understands how diseases act or how treatment works on a molecular level in non-white populations. As precision medicine develops, I’m hoping it is conscious of race and racism and that it can be used to help solve the problem of racial disparities. Society has a lot of work to do to make healthcare equitable for all.