Symbiosis/Dysbiosis

'Symbiosis/Dysbiosis' VR art installation will let you see, feel, hear the invisible

Tosca Terán and Sara Lisa Vogl speak with Massive about stimulating senses in their art

New Nature is a series of encounters between contemporary artists, filmmakers, immersive and VR creators, technologists, and climate scientists from Canada, Germany, Mexico and the US. (The project is an initiative by the Goethe-Institut Montreal, realized with the support of the Federal Foreign Office of Germany.)

Nature can feel you. Its roots, leaves, and vegetative filaments don’t sense with fingertips or retinas. But they can feel your approach and touch, react accordingly.

In a forthcoming art installation for the Goethe-Institut’s New Nature project, a group of artists want to translate these alien sensations and immerse you in their world. Their “Symbiosis/Dysbiosis” uses fungi, electrodes, lights, sound, and virtual reality to launch you in the microbiome all around you.

They aim to change how people view themselves within the broader environment. Tosca Terán, an expert in soundscapes, has spent years tapping into the invisible communication of plants and fungi. Their biosensing instruments, developed with Lorena Salomé, read imperceptible “biodata” from the organisms and convert it into melodies. The instruments also funnel a stream of data into a virtual environment developed Sara Lisa Vogl, a VR expert. Terán is also collaborating with Brendan Lehman, a neuroscientist and media artist, and Lorena Salomé to incorporate measurements of brain activity.

The result, they hope, will be an immersive, emotional experience that brings people closer to the chatter radiating from plant and fungal life.

Massive recently spoke with Terán and Vogl over video conference about their inspiration and expectations for this work. The following is a lightly edited and condensed version of that conversation.

Max Levy: Can you walk me through what I would experience if I visited this exhibit?

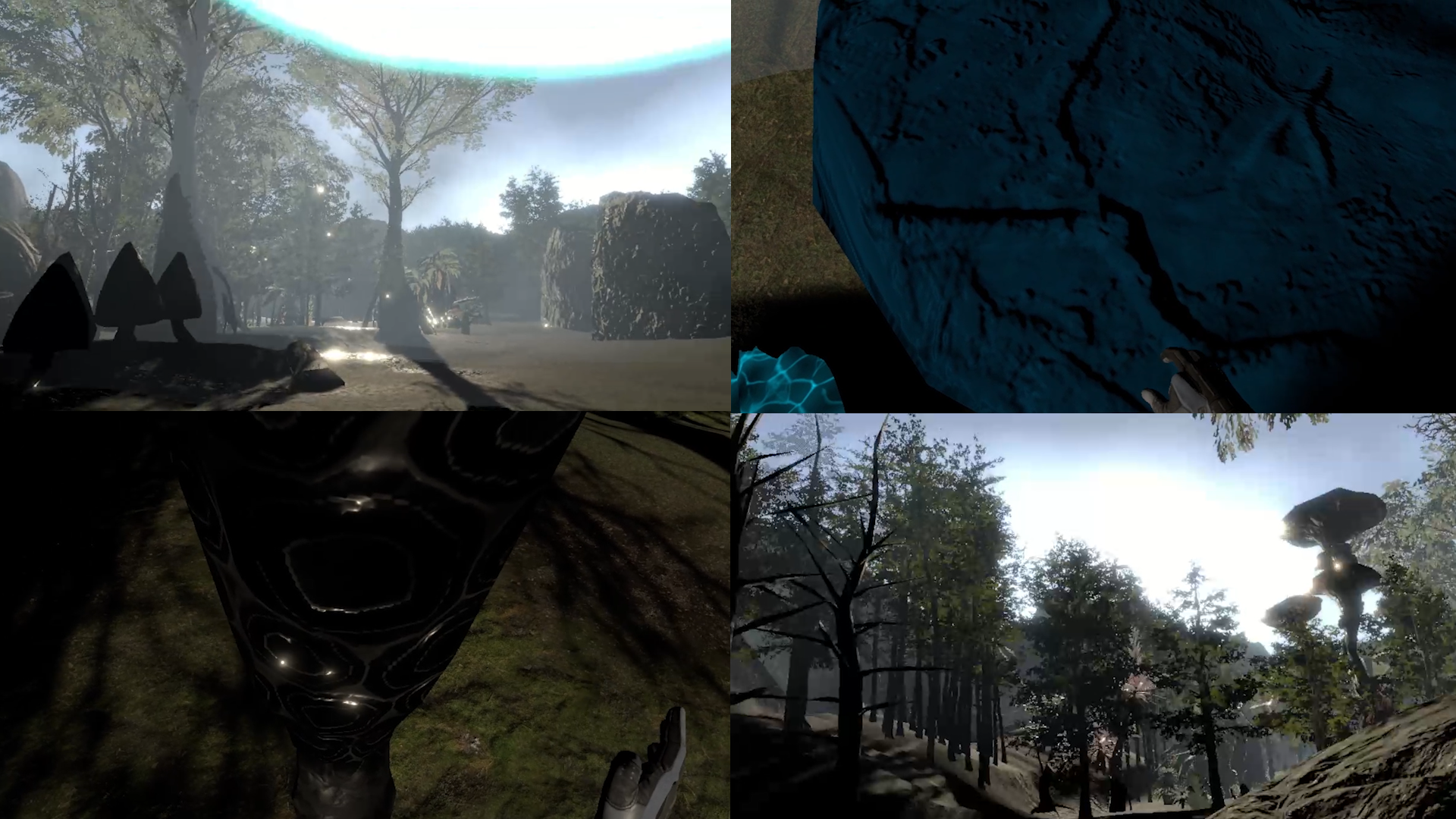

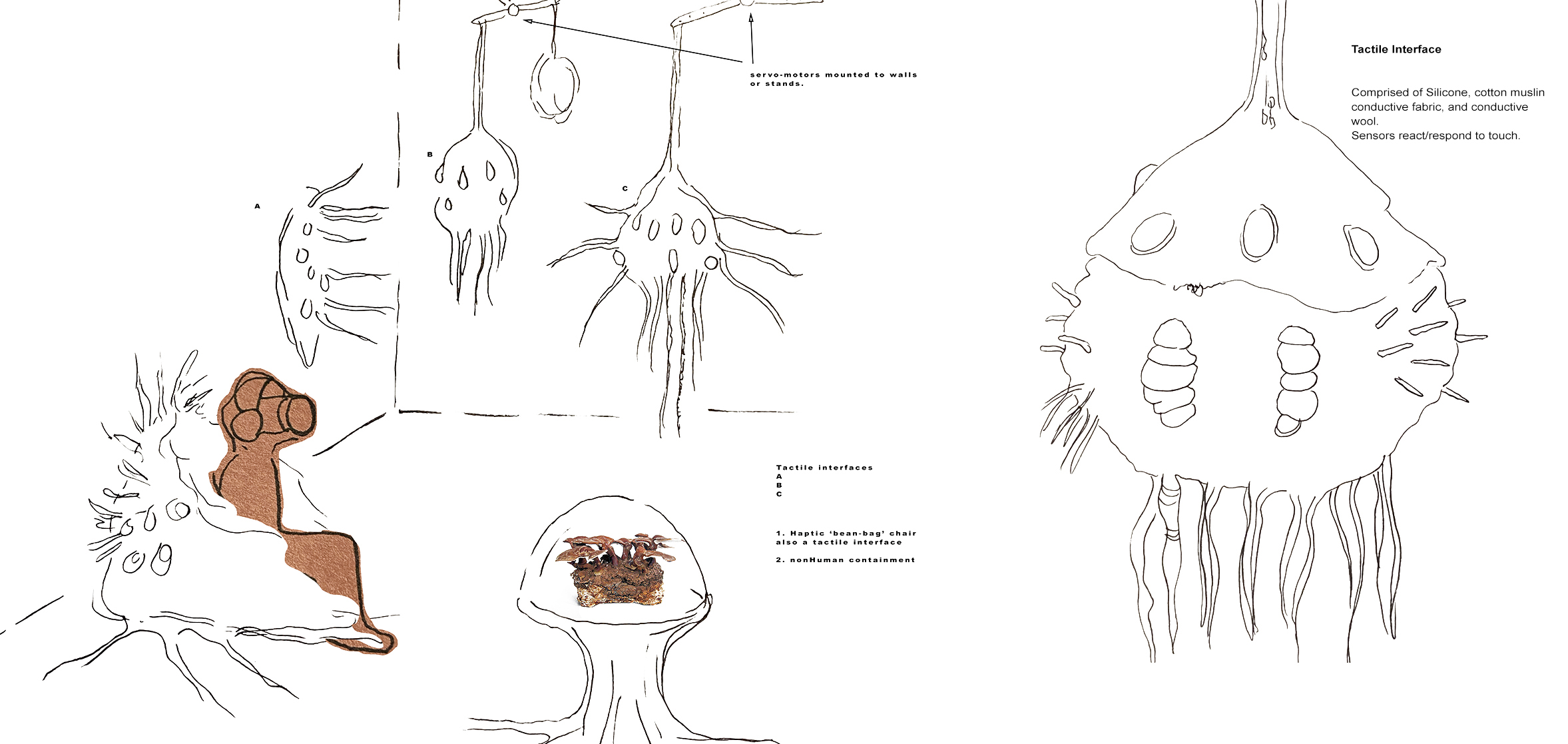

Sara Lisa Vogl: This is very much still growing and we are very much still in the design stages. The general mechanics that is happening right now is that there is a mycelium that is hooked up to electrodes that is basically setting the whole tone of the experience. And it should be set up in the way that this mycelium is on some kind of stand in a VR environment. If it's all set up correctly, the test subjects can really touch the mycelium in the real world and it's at the same time overlaid in the virtual reality. So that just grounds the user more in the environment, absolutely immerses them and makes the user feel more present in the environment that he's in.

You also have to be aware that the mycelium that hooked up to the electrodes, and whatever happened to them — just the pure presence of the human but also, of course, their touch and closeness adds to whatever sensory data we are getting. That sensor data is translated into music or into audio that is hearable in the space. But at the same time, it impacts the world that the VR viewer is in.

Sara Lisa Vogl

But we really want to work more on the reactivity of environments. We were brainstorming a whole lot of things in the beginning stages of this project of how the sensory data that comes can change the shape and the color, as well as the forms of the VR environment. And so that basically you have the reaction of the mycelium translated in visual and audio. And the reaction of mycelium is basically acting as the sensor, as the driver of the experience. That's connecting the real world and the virtual.

So these that are aspects that are partly done, partly not yet fully implemented in the VR experience. But this is all things we're thinking about and working on and studying.

Why is that sense of touch so important?

Tosca Terán: For this one test run, we hadn't been able to map the space to where the mycelium would be. I essentially held the mycelium up in its container. And I remember the woman that touched it — like, she reached out and was touching it in the VR space. The mushroom definitely responded right away, and the music changed.

And so what's happening in the environment is, if it was a positive reading, more birds could be heard singing, the forest became more alive in a very nice, pleasant way. And if it were the reverse of that — it wasn't so pleasant sounding.

Tosca Terán

But the person that touched it, they weren't aware that they were actually really touching something physically. So that's interesting to me anyways, on a psychological level. How are they processing that? And if it can be more immersive? And touch is one of those things, to me, that's fantastic. Like, I love the idea of going into a VR environment, and completely being lost.

What do you mean by a “positive reading”?

TT: So there's a lot that we're still having to research and figure out about this. When we bring the biodata into Unity, it's sending a lot of information. Generally, I tend to work with Ganoderma lucidum, which is Reishi mushroom. And on all the music things that I've done, my partner and I have just found it has the most, if you will, melodic response. It's very interesting how it responds to people. For instance, oyster mushrooms — we had those hooked up, and it was data non stop, no matter what time of the day, whether it was in a darkened environment, or with the sunlight, it was just very active — like, lots of info. So we were having to look at that and make a decision. Like if it dropped, like if the information dropped below a certain number, let's say then we might take that reading, and that would be dysbiosis for this moment. Or if it was fluctuating above, then symbiosis.

Symbiosis/Dysbiosis

What do you find most compelling when thinking of how to capture the science behind this project?

SLV: For me, it is really about a different interface and a different medium to explore sensations that I would otherwise hardly be able to feel and experience so directly. I think it's partly also making the invisible visible in a way that atunes more into my human senses. And so I can actually physically dive into not only science, but it's actually life. Right? So I can live or experience life and the exchange of energy, in a whole other way. So I think this is what is most fascinating for me in this project.

Is that also what draws you to biodata sonification, Tosca?

TT: Yeah, definitely making the invisible visible. I realize that in some ways, it's such an ambitious project but it's just hoping to make people more aware, that might experience it. That's been my impression overall with some installations that I've done — how moved people have been by the biodata-sonification of fungi, for instance. Some people think that plants are dead. That's what I've heard, because they don't see them moving, right? So just it's created a lot of conversations that are really great and educational on both sides.

Another aspect to mention that we're really interested in with the biodata is also using it through haptic technology. So deaf people can feel that — they can't hear it, they can feel it. And I feel that's really important too:just the empathy and compassion.

Especially. I don't want to go into the political realms of everything that's going on right now. But just bringing more awareness to people, or perhaps opening up at least a dialogue. It's very interesting to me.

Symbiosis/Dysbiosis

You’ve mentioned “awareness” several times. Can you unpack what you mean by that?

TT: I feel that, and I can only speak from my experience, that people don't even really think about how they're impacting, say, an environment or each other. And since learning more over the years about microbiome, or the different types of biomes, I've been super fascinated in just how that looks: like if we can see that and, obviously, hear that. And that brings in that biodata sonification. But for VR, it just seems to me like this fantastic media, to be able to kind of bring those visualizations to life.

In other installations I've done, people have been moved to tears, which has been very surprising to me. And they talk to me later about how they weren't aware — we tend to remove ourselves a lot from the non-human element in our shared environment. When I talk about perhaps bringing more awareness, or just maybe hoping for that, it’s [about] how we do have this shared connectivity. And we absolutely both impact each other. And symbiosis dysbiosis is how we are impacting that environment.

How has the pandemic affected your perspective on this project?

SLV: Every cultural activity, including going out and seeing this kind of installation is harder. I really want to see where this goes in the longer term because, if you're missing so much cultural life and influence — art has impacts on the current state of society — I think it will be a different world.

So I see it as a project that is definitely taking place in a very, very difficult space in time. Actually, funny enough, as we're doing this in VR, people could potentially do it at home. But of course, the whole mycelium setup, it's a bit much for people to install at home. The possibility at least is there to do these kinds of things remotely, hopefully more in the future.

VR experience called Lucid Trips, led by Vogl

Sara Lisa Vogl

When talking about VR for remote entertainment, it seems that the biggest barrier for sensory inputs is smell. How do you see smell fitting into this project?

TT: Well, we definitely have ideas for that for sure. Scent fans set up at head height, so you're in that breeze. I'm not a perfumer, but I have all kinds of scents to create certain smells. That to me is very fascinating. And it’s something we've kind of broached a bit, but we haven't implemented, we haven't gone there yet.

SLV: And yeah, definitely scent is a super, super powerful input. And I think it could totally be a wonderful extension to the current prototype,. It works super well in location-based entertainment, but again, location-based entertainment in these times is not the easiest thing to do. If we had been looking to even experience these things in our homes, I think there's still devices to be created. But there are a lot of super interesting attempts already in terms of bringing smell to VR environments that go beyond location-based entertainment.

What do you hope visitors will feel the moment they finish the exhibit?

TT: Last year, I was in Australia for a residency, I was hooking up gum trees, and things like that. The device I build detects micro fluctuations in conductivity between 1000 to 100,000ths of a second. And it translates that into MIDI notes and control. I can take that and bring it into a synthesizer or different things, so we can hear it, or we'll be feeling it.

So they had a huge field of these incredible flowers. They're called waratah flowers, and the director of the residency usually chops them down. And I just said, “Well, we don't need a bouquet in the house, we can just look out the window, and they're beautiful.” Anyway, so I had hooked up these flowers, and she heard the flower music, if you will. And the next day, I saw her out there with her clippers. She didn't see me standing in the studio, like.. watching her. She kept insisting she wanted to give us a bouquet of these incredible flowers. But she walked up to the flower and her head dropped and she just let the shears fall and she couldn't cut it. She came back into the house, found me and said “I can't do it now that I've heard them. I can't. I can't cut them.”

So, I mean, not that I wanted to stop her from cutting bouquets of flowers or anything like that. But it gave her pause. She just now considered this flower like: I'm going to cut this living thing, why am I doing this really, to put it in a glass jar?

So maybe for me, part of my reasoning behind this is that people have enjoyed the experience, but walk away and next time maybe they go into any environment, they're just considering the space differently.

This article has been produced as part of New Nature, a project by the Goethe-Institut realized with the support of the Federal Foreign Office of Germany. To find out more: http://www.goethe.de/canada/newnature

Ed. Note 12/9/20: A previous version of this story incorrectly attributed biosensing data to Terán and Salomé. Teran has developed this data individually, and has collaborated with Salome and Lehman to incorporate EEG data.