David Clode via Unsplash

Here's why insect protein could be the next whey powder

Changing the way we think about protein may have a big impact on the environment

Today we have more culinary options, and the ability to obtain more information to inform our diet choices, than ever before. Social media, in particular, has recently brought attention to non-Western cuisine—like eating bugs.

Although many cultures have long considered insects tasty, entomophagy—eating insects—has only recently caught on in North America and Europe. But eating insects can be a healthy choice, for both the environment and for humans. Compared gram to gram with conventional beef, raising insect protein requires 8 to 14 times less land, 5 times less water, and emits 6 to 13 times less greenhouse gasses. This is because insects have an incredible ability to convert their food into edible body mass. Because they're cold-blooded, they don't waste energy maintaining their body temperature. Since the whole insect is consumed, unlike animals, eating insects is also more efficient. A U.N. Report from 2013 suggests eating insects might be a critical way to help meet the almost doubled food demand predicted by the year 2050.

But insects are also a source of high quality protein, containing many essential amino acids required for human nutrition. They're also a good source of fatty acids, minerals—like iron, zinc, sodium, potassium, selenium, and copper—and vitamins, such as the B vitamins. Finally, insects contain dietary fiber, derived mostly from the chitin that makes up their exoskeleton. (Fiber is something most other animal products don't offer.)

Shira Gordon

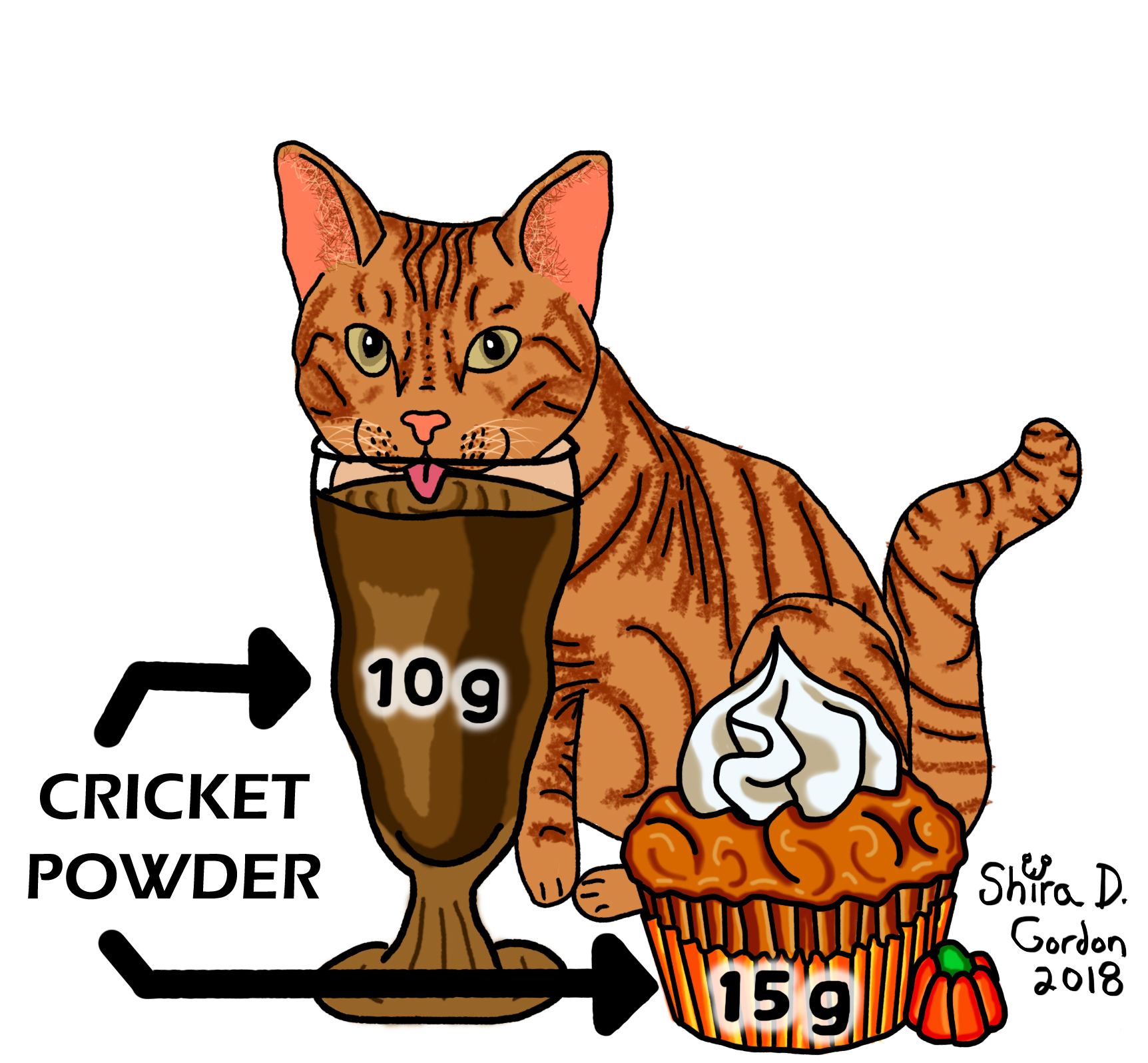

They might have health benefits beyond their mere nutritional content, too. Dr. Valerie Stull, a research scientist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, recently published a study comparing the gut microbiota of people before and after incorporating whole insect powder into their diets. The participants in the double-blind trial group received a prepared breakfast every day, including a pumpkin muffin and a protein shake, with 25 grams of cricket powder incorporated. The control group was also given foods with a similar macro- and micronutrient makeup, but without the added cricket powder. After two weeks, Dr. Stull assessed the changes in the subjects’ microbial gut content.

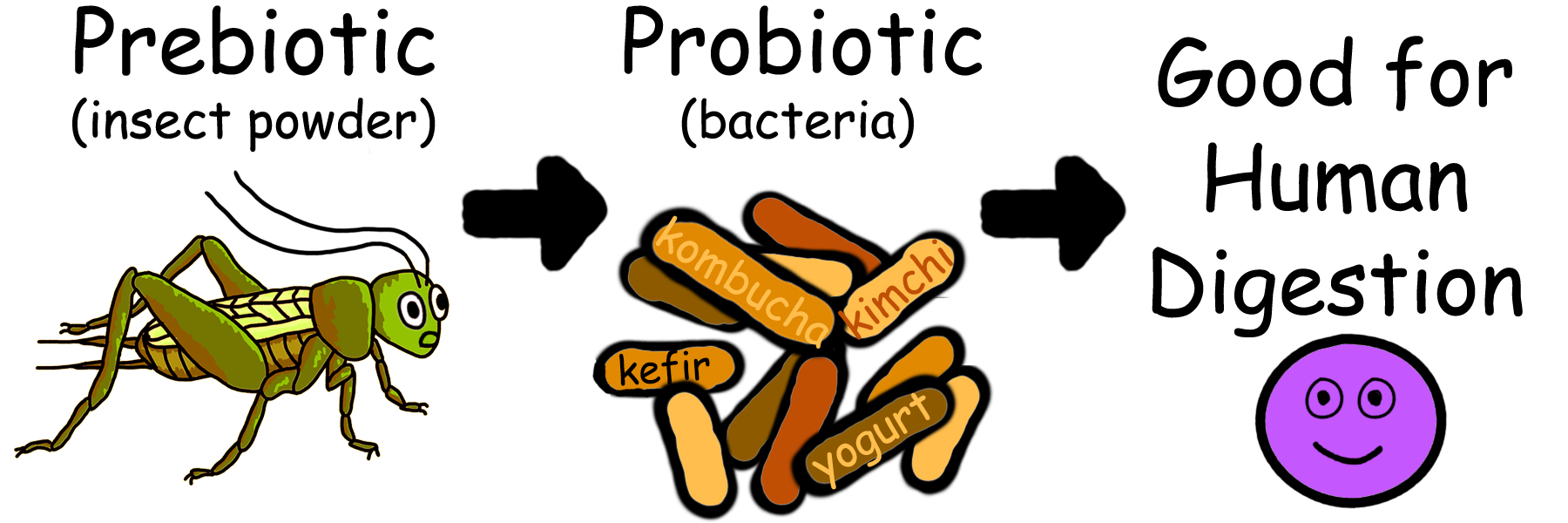

Eating insect powder, even for a short period of time, increased the abundance of Bifidobacterium animalis, which is considered a helpful probiotic. This bacteria can improve gastrointestinal functions and protect against diarrhea. The study suggests that insect powder itself can act as a prebiotic, meaning it's food for other beneficial bacteria that grow within the healthy human gut.

But as Dr. Stull says, “No one has really looked at the direct impacts of consuming insects on health, particularly how it might affect our gut microbiome.” She thinks that insect eating has “endless potential,” especially for people who are protein deficient.

Shira Gordon

Some cultures across the globe already regularly eat insects—approximately two billion people in over 130 countries. But Western society has been slow to embrace the idea. Some of these cuisine differences may stem from geography, according to Dr. Julie Lesnik, an assistant professor of anthropology at Wayne State University. She explains that centuries ago, when the world was much colder, insects were not available year-round in much of the northern hemisphere. So when Europeans started sailing the world, they did not consider eating insects, as insects were only present when other food went bad or as feed for animals, not as source of their own food. When they arrived in the Americas and encountered people that considered insects a common staple of their diet, the Europeans couldn't understand it.

“Explorers were shocked to see indigenous peoples in more tropical areas consume insects and immediately used this to judge them as animal-like,” says Lesnik. “If we look to the deep cultural history in Europe, insects were never a widely used resource.” Lesnik has recently published a book, Edible Insects and Human Evolution, where she explores the role of insects as part of the diet of early humans.

But today, insect protein represents a budding food industry, including in gourmet meals. In 2015, the commercial potential in the United States was estimated at $33 million dollars. Joseph Yoon, for example, a gourmet chef who has a culinary insect company, caters five-course insect-themed meals, and is planning events around the United States in 2019. (To see a gourmet meal made from insects, check out this video filmed at the biannual meeting of the North American Coalition for Insect Agriculture in 2018).

Shira Gordon

Companies across North America have started raising FDA-approved insects to fill the rising demand. Popular products include an insect powder, similar to the one used in Dr. Stull’s study, protein bars, whole insect snacks, and even protein chips. (Speaking from personal experience, “Chirps Chips” are tasty.) There are now many companies in the field and places to purchase them are proliferating. It may still seem a strange concept, but insect cuisine is likely coming soon to plates near you.