New evidence for the first life on land comes from an ancient microbial fingerprint

By comparing the chemical composition of modern microbial communities to their ancient counterparts, researchers can find better evidence of the earliest life on land. It's older than you think

Life evolved on Earth over three and a half billion years ago. Scientists still aren't sure how, but the general consensus is that it happened in the oceans. What we're still debating is when life arrived on land: depending on who you ask, it was either around three billion years ago, or just over 600 million years ago. Finding the answer will help us piece together the puzzle of life on Earth, and perhaps find signs of life on other planets.

To learn about the past, geologists often turn to the present. Biological soil crusts are modern-day microbial communities that live at the top of soils in dry environments. These communities are made of bacteria, fungi, and algae, who work symbiotically to pump nutrients throughout their 10-cm-scale ecosystem. Key among them are microorganisms called cyanobacteria, which have lived on Earth's surface for billions of years thanks to built-in chemical sunscreen for UV protection. Because cyanobacteria have been around for so long, scientists can study their biology, chemistry, and physical aspects of modern cyanobacteria communities on land, giving them a better idea of what to look for in the fossil record – and on other planets like Mars.

A new study, published in Astrobiology, adds a new piece to the life on land puzzle. Two of the key chemical "fingerprints" geochemists look for are carbon (C) and nitrogen (N), which are essential nutrients for all living organisms. C and N can be present in different chemical forms, called isotopes, depending on what organisms are there and how they're using nutrients. By measuring C and N isotopes in soil crusts in the southwestern U.S., the team of scientists from France and the US were able to precisely capture the chemical "fingerprints" biological soil crusts leave in the sediment. Then, like a forensic team, they could look at ancient fingerprints and see if they were a match.

Samples in the soil

Rebecca Dzombak

They compared their modern C and N fingerprint to that of a 3.2 billion-year-old rock that they thought was a fossilized land-based microbial community, based on physical evidence. It was a match, and for Dr. Ferran Garcia-Pichel, a geomicrobiologist who was on the team, that was strong evidence for ancient life on land as far back as 3.2 billion years.

"All the ingredients for forming that community... we know were present at that time," he said, "so why would [soil crusts] not have been there?" And without other vegetation to compete with, like crusts have today, the microbial communities would have dominated the surface. "They would not have just been on desert soils. They would have been on every soil."

Geochemists also need to be able to tell chemical fingerprints from cyanobacteria on land apart from aquatic bacteria that existed at the same time. For the most part, the crusts' fingerprint is distinct from other microbial signatures that could be left behind – but not entirely. Microorganisms living in the oceans, which can also be preserved in the rock record just like organisms on land, leave a big carbon-nitrogen fingerprint that overlaps with the soil crusts'. So how are they differentiated in fossilized sediment?

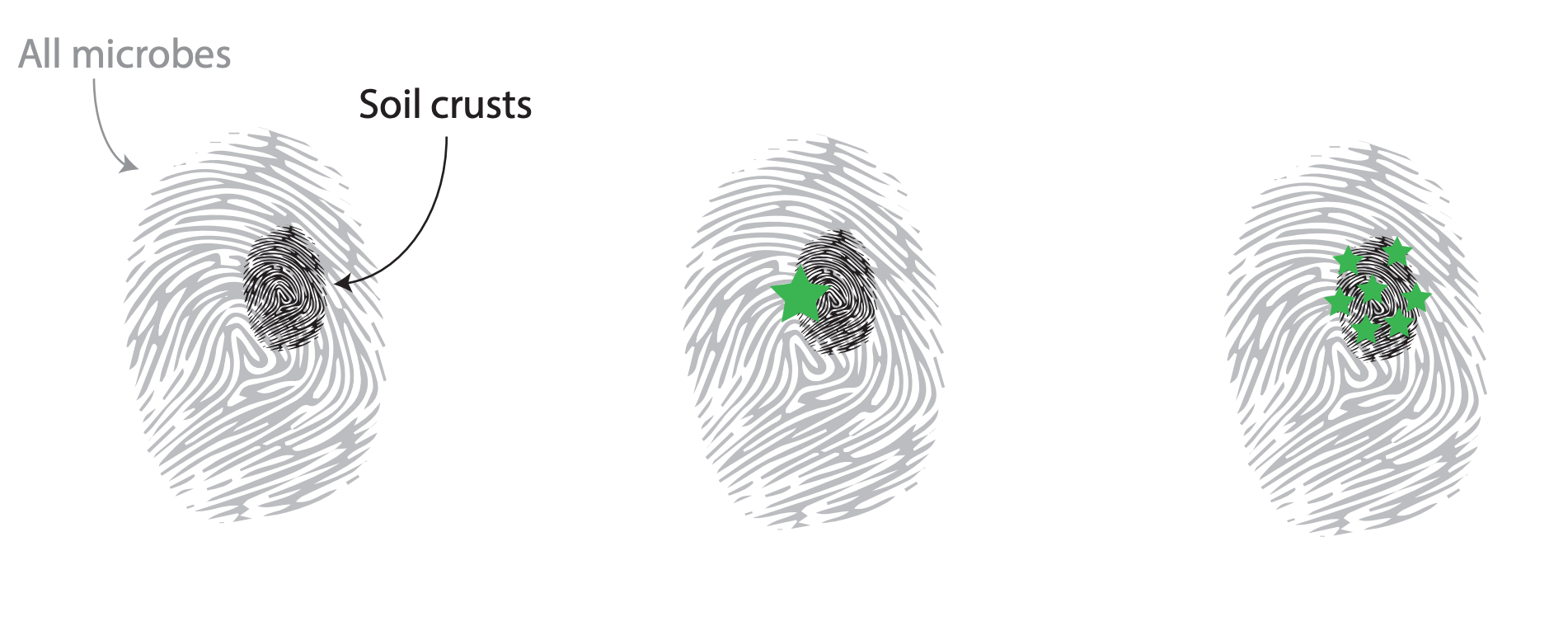

Part of it is contextual, like what rock type you're looking at, says Garcia-Pichel. "But it's a numbers game. You can't find one sample and say, 'the [carbon and nitrogen isotopes] are so-and-so, therefore it's a soil crust,' you have to have a cloud of data to define the bounds." In other words, you need a lot of samples to confirm you're looking at organic matter from ancient life on land, and not from water-dwelling organisms – which can be a problem if you're trying to find fossilized material that's three billion years old.

Why repeated sampling is important. If a soil crust is in one part of an entire bacterial community, sampling just once on its edge gives an incorrect impression of the entire crust.

Rebecca Dzombak

One boon for finding fossilized microbes? Land on early Earth was essentially a petri dish of bacteria, algae, and not much else, so cyanobacteria could thrive. Without any other vegetation, early soil microbial communities didn't have much competition. "In terms of their productivity, their impact, their potential – today is much more restrictive [for the crusts]," Garcia-Pichel said. "They wouldn't have just been on desert soil, they would have been on every soil."

Earth's low-oxygen atmosphere early on could have helped microbial communities turn into fossils. "[Crusts] are hard to fossilize... because the organic matter degrades very easily," Garcia-Pichel explained. "But if you go far, far back in Earth's history, there's an anaerobic environment, and there you can get an accumulation of organic matter." Layers of organic matter could have built up and been preserved, like microbial mats in specialized environments today.

Even so, finding ancient organic material with carbon and nitrogen to test isn't that easy, partially because there just isn't that much left. Once you've found organic matter, though, the quest isn't over: its chemistry could have changed over time. "The farther back you go in time, the harder it gets to know that what you're measuring is representative of the original values," Dr. Jenan Kharbush, a nitrogen geochemist who was not affiliated with this study, explained in an email. Carefully examining the chemical composition of organic matter can help ascertain whether or not it's been altered over time, but even then, it's not certain. "Essentially, the error bars get larger and larger [with time]... there's always a caveat that we usually never know for sure if something is original."

Now that biological soil crusts have been duly fingerprinted, the next steps are adding in more geochemical work – like looking for specific patterns of elemental depletion – and in analyzing more potential ancient microbial communities. As more rocks are analyzed for C and N fingerprints, the history of life on land will become clearer. These tools aren't limited to a search for ancient life on Earth, though. Because sediment geochemistry is one of the main tools for extraterrestrial exploration, any findings on Earth can be applied to results from the Mars rovers, too.

"One of the main goals of the Perseverance rover is to search for potential ancient microbial biosignatures," Dr. Briony Horgan, who is on the Perseverance team, says. The rover will be mapping Mars rocks' chemistry and collecting samples, but the real insight won't come until those samples are back in Earth labs. "These measurements alone won't be enough to confirm the presence of biosignatures, in part because we think measurements like isotopic chemistry are so important... Once we have those samples in hand, we can apply all of the techniques we've learned for detecting biosignatures in Earth samples, including isotopic chemistry."

With these results, geologists and biologists are one step closer to agreeing on when life evolved on land, and astrobiologists can use this improved chemical tool to find signs of extraterrestrial life. So next time you find yourself in the desert, take a look at the ground and see if you can spot dark, lumpy soil. That's the biological soil crust, and it holds the keys to finding ancient life on Earth and beyond.