Neurotoxins in the water supply worsen the impact of Zika virus

A neurotoxin produced by cyanobacteria may help explain patterns of Zika-associated microcephaly in Brazil

Photo by Егор Камелев on Unsplash

Zika virus is transmitted by Aedes aegypti — a mosquito that also transmits dengue and yellow fever. In some people, the virus causes symptoms that are very mild. Other cases, however, are dramatic — fetuses that are infected inside the womb can develop microcephaly, a condition in which the baby's head is much smaller than expected. Unfortunately, many cases were reported in Brazil during the recent outbreak of the disease.

The situation motivated Brazilian researchers to search for answers. Some were found quickly: in 2016, a paper described how the virus affects the development of brain organoids. But a big question remained unsolved: why were the microcephaly cases concentrated in northeast Brazil when Zika was spread throughout the country?

Various hypotheses were on the table: folic acid deficiency in pregnant women in northeastern Brazil, coinfection with other mosquito-transmitted viruses, extreme poverty, or even the use of pesticides in agriculture. But nothing seemed to explain why there were so many cases of microcephaly in this particular region.

An interdisciplinary team lead by neuroscientist Stevens Rehen, from the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, recently published a preprint that adds one more piece to that puzzle. The group investigated how environmental factors can influence the development of microcephaly.

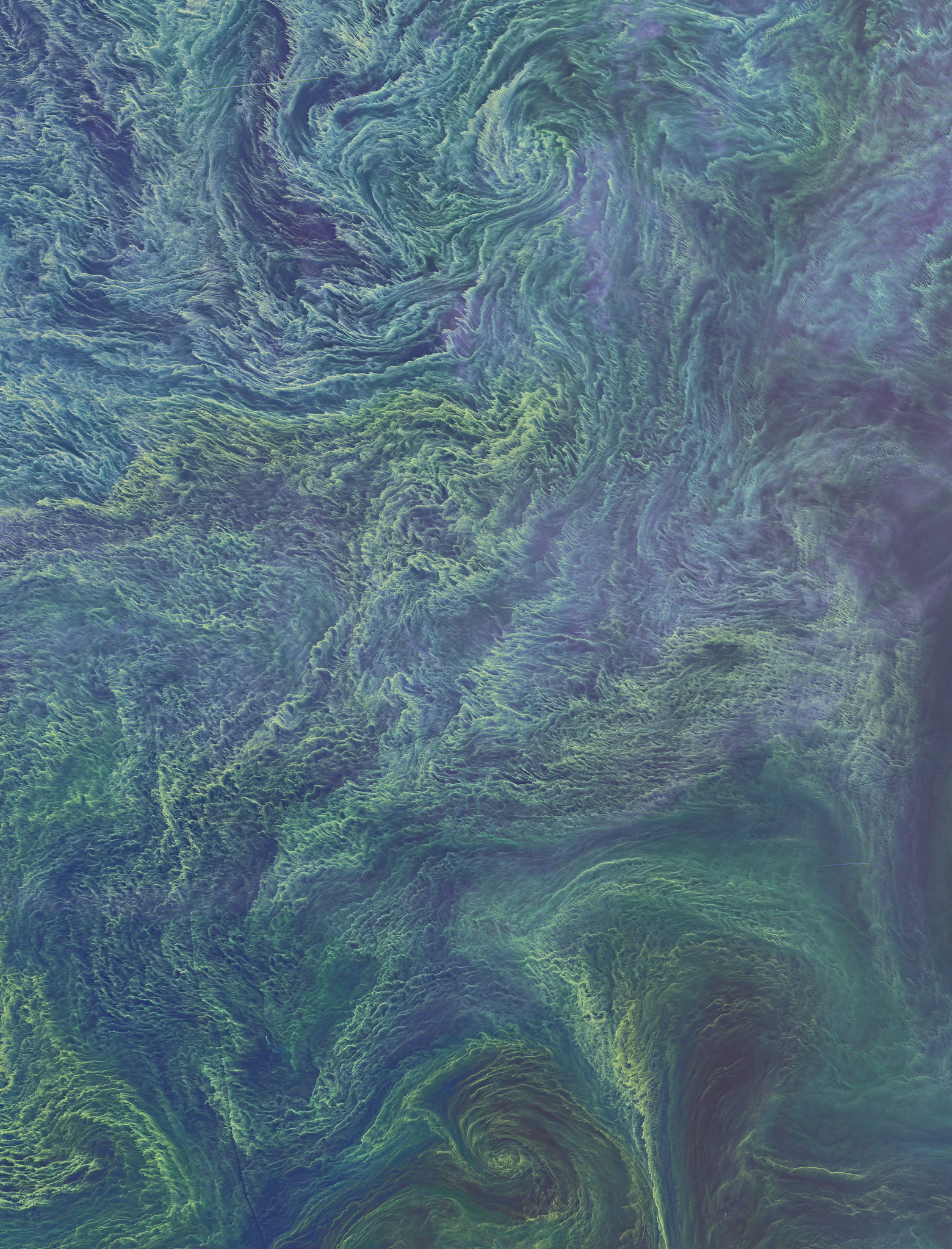

Northeastern Brazil suffers from drought periods, which can lead to blooms of cyanobacteria. Those microorganisms often produce toxins that can be harmful to human and animal health.

NASA Goddard Space Flight Center

The new hypothesis to explain the microcephaly boom in northeast Brazil involved saxitoxin, a neurotoxin produced by the freshwater cyanobacteria Raphidiopsis raciborskii. Perhaps because of a severe drought in the region from 2012 to 2016, there was a higher saxitoxin occurrence in the drinking water supply of northeast Brazil compared to the rest of the country.

In the lab, the team showed that the presence of saxitoxin doubled the cell death rates in progenitor areas of human brain organoids infected by Zika virus. Scientists now believe that this might explain why microcephaly was worse in the northeast region.

Due to the complexity of the Zika outbreak in Brazil, the scientific community had to exercise true detective skills. Scientists had to go beyond their own lab walls and connect different knowledge areas to solve the puzzle. Hopefully, these new findings will help to prevent future cases of Zika-associated microcephaly.