Lab Notes

Short stories and links shared by the scientists in our community

Hermit crabs are using old bottle caps and plastic as shells — and it's killing them slowly

Around 570,000 crabs become entrapped in debris each year on the Henderson and Cocos (Keeling) islands

By David Clode on Unsplash

Unlike many other crustaceans, hermit crabs don’t have their own hard shell to protect them. Instead they find an empty shell, often left behind by a sea snail, to climb in. However, hermit crabs are not particular about their shell: in fact, an artist convinced hermit crabs to use 3D printed shelters in the shape of famous cities.

Because of this, we might expect that hermit crabs are quick to adapt to increasing amounts of plastic on their beaches. Indeed, crabs have been found using old bottle caps and other plastic objects as shelters. But a new study by Jennifer Lavers from the University of Tasmania shows that this plastic is in fact incredibly damaging to hermit crab populations.

The major danger for the crabs is plastic bottles that wash up on shore. If these bottles don’t have a cap or have a hole of some sort, the hermit crabs may climb in them. However, they often can’t climb out again and get stuck without food and water, causing them to die after about a week.

Hermit crabs as seen in Okinawa.

Dori Grijseels (2019)

This is the start of a chain reaction. Hermit crabs rely on their shells to survive, and good shells are hard to come by. If a crab dies, it releases a special odor that other crabs can detect. They will climb into the bottle in search of the shell of the dead crab, but get stuck themselves. This was probably the cause of the single bottle with 526 hermit crabs stuck in it that the researchers found. They estimated the total number of hermit crabs that got stuck in bottles on the Cocos (Keeling) Islands and Henderson Island was about 507,000 and 62,000 respectively.

We often hear about the damage plastics cause in our oceans, but this research shows that the effects are not limited to marine environments. Many terrestrial animals are also endangered by the plastics that accumulate on beaches. If we don’t reduce the amount of plastics that end up in the ocean, we could risk extinction of these species.

Forget Google Glass, you may be able to wear smart contact lenses sooner rather than later

The future of smart contact lenses is looking up

You’ve probably heard of the Google Glass (and its demise), but there are more vision-based wearables in development, including smart contact lenses. Smart contact lenses are not yet available on the market, partly because they face additional technical challenges. Most people might overlook the inconvenience of wearing spectacles, but we probably won’t see eye-to-eye on the matter of placing an electronic device directly on our eyeballs.

Recently, a group of South Korean researchers demonstrated that their latest smart contact lens design is indeed feasible, going as far as to demonstrate for the first time that their prototype can be worn safely by humans.

It seems so — it is made from hybrid nanomaterials encased in a soft, stretchable polymer. The lens can be elongated up to 1/3 more than its original dimensions, repeatedly too.

Is the lens safe? Check — it operates at low voltages and maintains a stable temperature far below body temperatures.

Is it convenient to use? Why, yes — it can be wirelessly charged to full power in four minutes. The researchers claim that their smart contact lens are the first that can be operated continuously, thanks to a built-in supercapacitor. The supercapacitor stores a large amount of charge per unit volume and releases it, allowing for continuous function.

How is this contact lens “smart”? Well, it blinks. So far, its only function is for an embedded LED to turn on and off.

Nevertheless, this research has cleared the major technical hurdles. Now, it behooves the rest of society to ask why we should want smart contact lenses.

Previous attempts by major companies have had outlooks far from eye-catching. Google Contact Lens was conceived in 2014 for monitoring glucose levels in tears, but the project has been discontinued because of measurement inaccuracies. Samsung has filed several patents to develop smart contact lenses for augmented reality, but a concrete product remains nowhere near market-ready. If we blindly chase after the bandwagon, then smart contact lenses might suffer the same fate as the Google Glass.

Here's how earthquakes rocked Puerto Rico into another emergency

Multiple events shook Puerto Rico's southern coast

Photo by MJ Tangonan on Unsplash

The moderate earthquake in Puerto Rico makes January 5th's 5.8 a foreshock (Ed: a tremor that occurs before a larger event, the mainshock). There have been several earthquakes over the past few days along the southern coast of Puerto Rico.

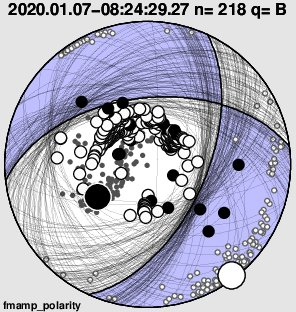

The map below is from the IRIS interactive view, showing earthquakes since Saturday with depth in color (purple = <33 km) and size denotes magnitude. The east circle represents the largest event, which is not quite co-located with the other events.

Michele Cooke

The focal mechanism shows normal slip event with some strike-slip (Ed: one kind of motion involved in an earthquake, where plates are moving horizontally relative to each other) and the expected seafloor displacement triggered a tsunami warning, which was cancelled.

Anthony Lomax

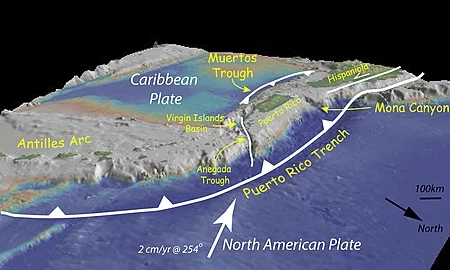

The following image from Wikipedia views Puerto Rico from the northeast showing the Puerto Rico trench to the north of the island and the less active Muertos Trough to the south of the PR. The recent shallow normal-strike-slip slip seismicity is likely related to the deeper Muertos trough. Like other islands in the northern Caribbean, strain within Puerto Rico is partitioned with off-shore subduction zones and on-shore strike-slip systems.

You've probably seen the reports coming out of Puerto Rico of widespread damage from shaking. The soft first story of many buildings have collapsed. When you think "soft first story," think of vertical posts to support the house so you can park underneath. When the ground shakes, these posts are very unstable.

We will likely learn of more damages and fatalities with time. I hope that the federal government acts quickly to support our fellow citizens in crisis in and not repeat mistakes made after Hurricane Maria.

Coral reef bacteria are being killed off by human activity

Microbes could provide important clues about the health of coral reefs

Photo by Marek Okon on Unsplash

Across the globe, coral reefs are in trouble. One of the biggest challenges we face today is figuring out how to save them. Like any good doctor, we need an efficient and reliable way to determine how sick or healthy different coral reefs are. A team of researchers from the USA, Mexico and Cuba wonder if reef microbial ecology might be the answer.

Photo by Francesco Ungaro on Unsplash

To understand how the microbial community differs between different types of reefs, the team sampled water from different coral reefs on the coasts of Florida and Cuba. Jardines de la Reina in Cuba, a reef that has been largely protected from human activity, had the richest microbial community. This area was especially rich in bacteria that can perform photosynthesis and cycle nitrogen, thus increasing productivity in the region.

In contrast, the site that had been most impacted by human activity, the Florida Keys, had a smaller and more variable microbial community. Disturbances like overfishing, coastal development and nutrient run-off in the Keys seem to have produced a small but competitive group of microbial residents. Studies like these can help us understand how human activity can disturb the microbial communities of coral reefs.

Previously used metrics like coral coverage and algal coverage did not vary significantly between these reef systems, indicating that these might not be the best metrics to measure coral reef health. Perhaps it's time to let the microbes speak and tell us the true story of coral reef health.

Nanoparticles could one day store your vaccination record in your skin

Quantum dots successfully provide in-skin vaccination record (in rats)

Heather Hazzan, SELF Magazine

Vaccines save 2-3 million lives around the world annually. However, 1.5 million deaths from vaccine-preventable diseases still occur each year. Although many factors may lead to undervaccination, one important factor is the inability to accurately determine whether an individual has previously received a given vaccine, especially in developing countries where many people may not have vaccination records.

Several alternatives to the traditional paper records have been proposed, including smartphone-based databases, fingerprinting and communication chips. However, these expensive options have not yet become prevalent due to difficulty in implementation.

In a recent study published in the journal Science Translational Medicine, a group of researchers, including scientists from MIT and the Chinese Academy of Sciences, has come up with a cheap and easy-to-implement solution. They have designed a system to administer and detect very small nanoscale particles called quantum dots. The quantum dots are administered along with the vaccine and remain in the skin, serving as a vaccination record.

First, the researchers had to synthesize the quantum dots, which are very small crystals, in the range of 2-10 nanometers. These particles are widely used in biomedical imaging, photovoltaic cells, and some TV screen displays. Scientists selected one type of quantum dot (called S10C5H) for its structural and functional stability under simulated sunlight. The quantum dots were then encapsulated in micro-sized capsules made of a special polymer. These encapsulated particles wrapped in pigmented human skin showed stability upon exposure to simulated sunlight up to an equivalent time of 5 years. The encapsulated polymers were packed in microneedles that were designed to dissolve in the skin.

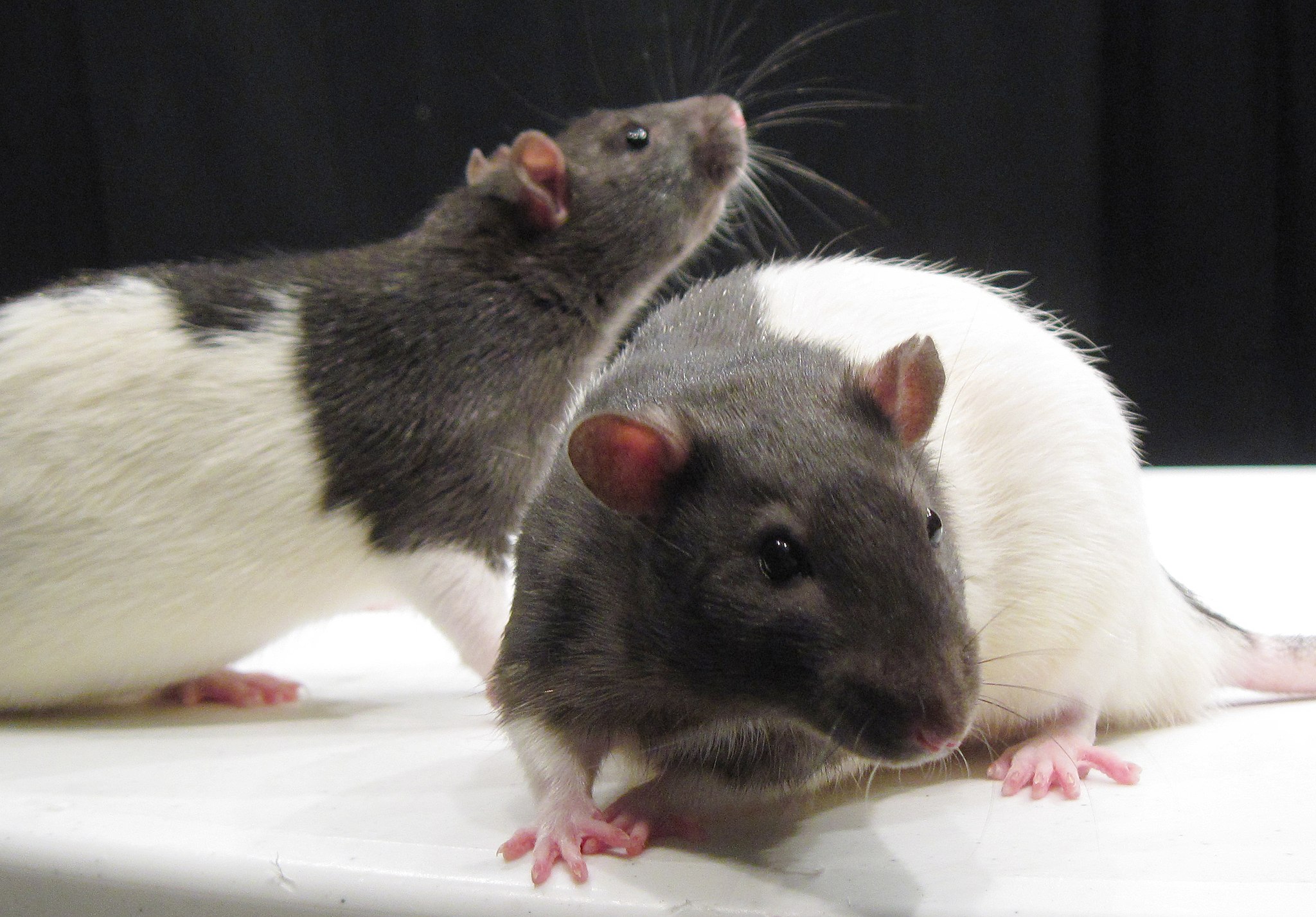

A pair of black and white rats

Jason Snyder on Wikimedia Commons

The researchers subsequently treated rats with these dissolvable microneedles containing the polio vaccine and quantum dots (as the record of vaccine administration). No significant unaccounted tissue damage or toxicity was observed in the rats. The quantum dots could be visualized only under special LED lights in the near-infrared region (like the waves emitted by remote control), so they are invisible to the naked eye. For imaging purposes, researchers designed special lenses and imaging software for a Google Nexus 5X smartphone. Scientists found that the record-keeping quantum dots remained visible under near-infrared light for at least nine months. Furthermore, the dots did not seem to negatively impact the effectiveness of the vaccine: animals had antibody levels that were considered high enough to protect them from the disease.

For effective usage in the real world, clinical studies assessing biocompatibility and potential toxicity of the encapsulated dots will have to be done on humans. Overall, this study opens new and exciting possibilities for medical data storage, which could prove very valuable in eliminating vaccine-preventable diseases.

DNA barcodes help identify fish eggs and inform conservation

Determining where fish spawn could help us protect these crucial habitats and bolster declining fish populations

Photo by Vlad Tchompalov on Unsplash

Fish are economically and ecologically important in the Gulf of Mexico, yet their stocks are decreasing due to overfishing. One major way that we can help protect fish is to protect the habitats where they reproduce. But in order to do that, we first have to find out where they reproduce. One way to find these spawning habitats is by using floating fish eggs.

.jpg)

Nicole Seiden

Before setting up projects focused on reef fishes, like grouper and snapper, we needed to know if eggs from shallow water fishes stay in the shallows or if the eggs move into deeper waters as they float.

Fish eggs can be found in most surface waters, making them easy to collect with a plankton net. However, these eggs are usually clear balls the size of the tip of a pencil, making them difficult to visually identify down to species level. To solve this problem, we use a laboratory method called DNA barcoding. DNA barcoding allows us to look at the genetic material of each fish egg to figure out which species it belongs to. Each species has a unique DNA signature, just like how each product at a grocery store has its own unique barcode.

Using DNA barcoding, we found that most shallow water fish eggs stay in shallow waters. This information will help us plan future fish egg collections to help inform fisheries managers where and how much these shallow water species are spawning.

Photons pop in and out of existence to transfer heat

It isn't heat conduction, convection, or radiation

When we learn about heat transfer in school, we learn there are three types: conduction, convection, and radiation. But scientists have finally observed a fourth type of heat transfer, and it's all thanks to quantum mechanics.

One main principle of quantum mechanics is so-called zero-point energy, or vacuum fluctuations. This means that, even at a temperature of absolute zero, a system will still have some amount of energy. This causes all sorts of bizarre phenomena, like particles randomly popping in and out of existence near a black hole, or, in this case, photons popping in and out of existence between two plates of metal. Known as the Casimir effect, these short-lived, "virtual" photons can transfer energy from one of the metal plates to the other.

The scientists observed the effect in this new experiment by making the metal plates out of a deform-able material that can vibrate like the head of a drum. Each of these drumheads were tethered to blocks at different temperatures. Heat from the blocks caused the atoms in the plates to jiggle faster, making them vibrate. But because the blocks were at different temperatures, the two drumheads vibrated with different amounts of energy. When they were brought close enough together, the scientists saw that the Casimir photons took energy from the hotter drumhead and transported it across the vacuum to the cooler one, until the two were in thermal equilibrium.

Overall, the influence of quantum mechanics on everyday human experiences like temperature is a hot research area, and I personally find it pretty cool!

Ice Bucket Challenge donations have helped fund promising ALS clinical trials, especially for "fast progressors"

There are currently only four drugs approved to help treat amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)

By Major Tom Agency on Unsplash

Promising results from a Phase 2 clinical trial show AMX0035 (Amylyx Pharmaceuticals), a combination of sodium phenylbutyrate and tauroursodeoxycholic acid, may slow disease progression in individuals with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). The news comes days after the passing of Pete Frates who championed the ‘Ice Bucket Challenge’, raising global awareness of the devastating disease and over $200 million for research and advocacy efforts. The trial, known as CENTAUR (Combination of Phenylbutyrate and Tauroursodeoxycholic Acid), was funded in part by Ice Bucket Challenge donations.

ALS affects approximately 16,000 people across the United States, and only four drugs are currently approved to help treat the disease. In ALS, a loss of nerve cells that control movement (motor neurons) leads to progressive muscle weakness. As the disease progresses, people with ALS experience difficulty with movement, speaking, eating, and breathing, and may require interventions such as a tracheostomy to prevent respiratory failure.

The CENTAUR clinical trial found that research participants taking AMX0035 had a significant reduction in disease progression compared to placebo, as measured by the ALS Functional Rating Scale. Notably, enrollment criteria for the study selected 'fast progressors' — a subtype of participants believed to be more likely to show an effect (if there is one) during a trial — by studying a database of over 10,000 people with ALS. In an interview with Neurology Live, study principal investigator Dr. Sabrina Paganoni stated, "These patients are not biologically different from other people with ALS; this was basically a statistical strategy to increase our power to see a treatment effect with a relatively smaller trial." Participants are being invited to enroll in an open-label extension study, providing everyone with access to the study drug and an extended follow-up period.

Prior research studies have found that sodium phenylbutyrate improved outcomes in an ALS mouse model and provided neuroprotection, while tauroursodeoxycholic acid reduced endoplasmic reticulum stress and prevented neurotoxicity. Both tauroursodeoxycholic acid and sodium phenylbutyrate were each individually tested in people with ALS, but there was no larger-scale follow-up of the compounds until now. Amylyx Pharmaceuticals found the combination reduced cell death, prompting the current trials in ALS as well as Alzheimer’s disease.

Being exposed to reactive oxygen helps worms live longer lives

Worms exposed to reactive oxygen species early in life actually lived about 18% longer than their unexposed counterparts

The most widely accepted theory of ageing is that reactive atoms or molecules of oxygen, referred to collectively as reactive oxygen species (ROS), damage molecules like lipids, DNA and proteins. Accumulation of ROS has been implicated in many age-related diseases, including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic kidney disease, neurodegenerative diseases, and cancer.

In a recent study published in Nature, a team of scientists from the University of Michigan and the Chinese Academy of Sciences have discovered that roundworms (Caenorhabditis elegans) exposed to high levels of ROS in the early stages of their development are more resistant to oxidative damage, and this allows them to live longer. Roundworms are powerful biological model organisms as most of their genes have functional counterparts in humans. So, this could illuminate how to mediate the effects of aging in humans, as well.

The group studied two different groups of roundworms who experienced different ROS levels during early development, allowing them to categorize the worms as being in one of two states: oxidative (stressed) and reduced (normal). Both groups of worms went on to have similar ROS levels to each other in early adult stages. However, by late adulthood (day 7 in worms), they saw that the oxidized group had significantly lower ROS levels than the reduced group, and they were living about 18% longer.

The researchers also looked at gene expression patterns in the two groups of worms to determine the molecular mechanism of the stress resistance. They found a major difference in the way that proteins called histones function. Histones package and order DNA. An enzyme called H3K4me3, which alters the chemical structure on the surface of the DNA, was found to be reduced in the worms that had been part of the oxidated group early on. This modification acted as a form of memory for the cells and led to increased stress resistance in later life.

This study establishes how early-life events alters DNA expression throughout an organism's life and ultimately leads to stress resistance and increased lifespan. One next step is to look for evidence that similar mechanisms play a role in human aging. This important study might eventually lead to improved treatments for age related degenerative diseases.

Not surprisingly, science still has a huge racism and sexism problem

All STEM fields have this problem, with physics having particularly large gaps

CDC

Stereotypes about others’ gender and race can influence the way we perceive and judge them. Such biases have been shown to affect employers’ hiring decisions, even when evaluating “fake” but identical resumes. A 2019 study examines how intersecting stereotypes about gender and race influence professors’ perceptions of fictitious post-doctoral candidates applying for positions in different STEM departments at universities.

In science, as the study shows, there is still a tendency to view women as less competent and hireable than comparable men, but fields that are more male-dominated (i.e., physics) appear to be more discriminating than those that are more gender-balanced (i.e., biology). Meanwhile, Black and Latinx PhDs, especially those who are women, tend to be viewed as less competent or hireable than comparable White and Asian PhDs.

We’ve known there to be racism and sexism in the academy for a long time, but what is unique about this study is that the authors took an intersectional approach to their analyses. For instance, instead of just looking at the effects of race (i.e., black vs white applicants) or gender (i.e., men vs women) on professors’ ratings of applicants’ hireability, likability, and competence, the authors made sure to analyze the effects of intersecting identities (i.e., Black/Latinx/Asian women, Black/Latinx/Asian men in comparison to white men/women) on such outcomes. Their results highlight how understanding the underrepresentation of women and racial minorities in STEM requires examining how racial and gender biases intersect.

What I found most interesting about the study’s findings is that even though physics and biology are both STEM fields, the discrimination against women was found more so in physics, where women are severely underrepresented compared to biology (Women earn a little more than half of doctorate degrees in biology but only one-fifth of the doctorate degrees in physics). Similarly, the study also found that Asian applicants were not discriminated against compared to black and Latinx candidates, which further supports the point about representation in STEM fields making a difference in how job candidates of different groups are perceived and rated for those jobs.

These findings raise some important questions and implications about gender and racial discrimination in STEM. Would women be more accepted in currently male-dominated professions if those professions were more gender-balanced? Do women and some racial minorities appear "out of place" in physics because they are underrepresented in that field as it stands, thus leading to hiring biases? Are women relatively accepted in the life sciences because such fields have become more “feminized” over the years and, thus, are perceived as “easier” to excel at?

We need better volcano forecasts to prevent tragedies like New Zealand's Whakaari explosion

Researchers are working on modeling eruptions to prevent loss of life when volcanoes explode

Photo by Farrah Fuerst on Unsplash

Two weeks ago, Te Puia O Whakaari Island, off the coast of Aotearoa (New Zealand), erupted, killing at least 16 people. The volcanic alert level for the island was raised to Level 2 in November, suggesting the volcano may be entering a state of increased volcanic activity. But what does a Level 2 mean? And is it even possible to forecast when a volcano can erupt?

Raising the volcano to a Level 2 indicates changes in volcanic parameters (like seismic activity). Levels 1 and 2 relate to volcanic unrest, while levels 3-5 indicate current eruptions. GeoNet, a hazard monitoring program of Aotearoa, indicates that eruptions can occur at any level on the scale, and sometimes no eruptions occur even after alert levels are raised. After the island was raised to a Level 2, an eruption likelihood was calculated on December 2nd, estimating an 8 to 14% chance of an eruption in the following 4 week period. The eruption occurred 7 days later on December 9th.

Photo by Farrah Fuerst on Unsplash

A sub-discipline of volcanology research is centered around improving forecasts of when volcanic eruptions may occur. While strides are being made in this area of research, not all volcanic eruptions are the same, and some are harder to forecast than others. Monitoring around active volcanoes is used to forecast if an eruption is possible in the near future. Parameters such as seismic activity, flow of electrical current through rock, deformation of the ground around the volcano, and changes in the gas emitted from volcanoes (such as an increase in sulfur dioxide) may all be a precursors to an eruption and are often part of a monitoring program. However, changes in these parameters may occur without an eruption, and sometimes eruptions may even occur without any notable changes in those parameters.

The Whakaari eruption was a steam-based eruption, among the hardest to monitor. Shane Cronin, a Professor at the University of Auckland, explains that in these types of systems, water is trapped in rock pores, and any changes in the system may cause a sudden expansion of the water into steam, leading to catastrophic eruptions.

The likelihood of continued eruptions of Whakaari are steadily decreasing, but these events beg the question of what can be done to assure safety of those who live near and travel to active and dormant volcanoes. Massey University volcanologist Associate Professor Gert Lube and others were recently awarded a million New Zealand dollar grant to test volcanic eruptions and flows, similar to those that occurred in Whakaari, using computer simulations. They hope their research will help more effectively assess risks associated with volcanoes like Whakaari.

Could radiation in deep space fry astronauts' brains?

New research in mice suggests that long-term low-dose radiation impairs learning and memory

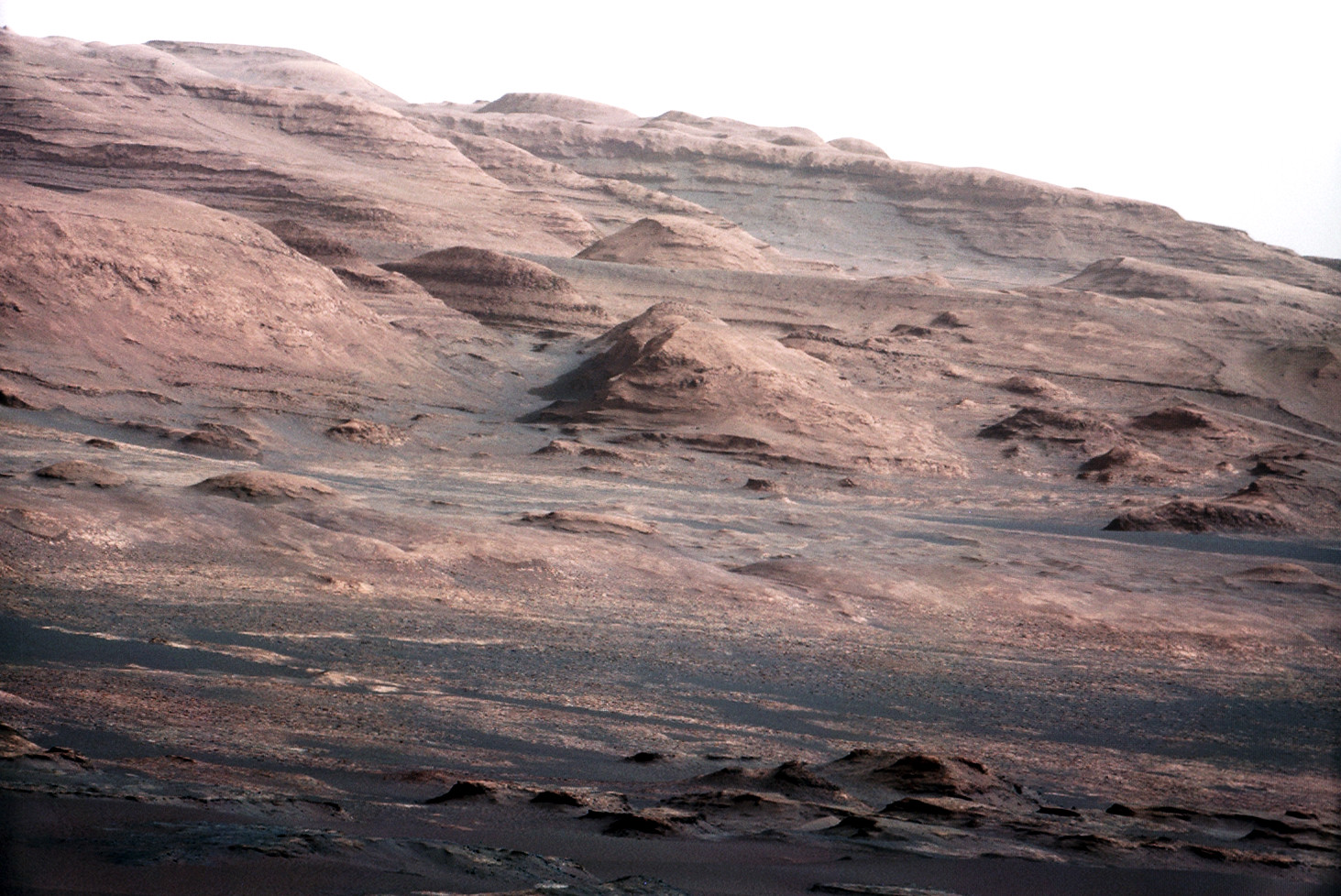

Kevin Gill via Flickr

Even though it happened half a century ago, the Moon landing remains one of the most ambitious space exploration projects ever. The future, however, holds even more exciting and longer flights. It takes about a week to get to the moon and back, depending on the route. But the much-talked-about trip to Mars would take us, at a minimum, 8 months — one way. During those months, aspiring interplanetary settlers would be exposed to a constant dose of radiation, without the protection usually afforded by Earth’s magnetic field.

We are still unsure about the impact that this radiation exposure could have on astronauts’ bodies. New research done by a group led by Charles Limoli, a radiation oncologist at the University of California, Irvine, suggests that chronic, low dose radiation can lead to severe impairments in learning and memory, as well as distress behaviors — at least in mice.

In this study, the scientists exposed mice to radiation at a rate of 1 milligray per day for 6 months — a relatively low dose that is comparable to what a deep-space astronaut would encounter. After this exposure, the scientists examined the hippocampus of the mice, the area of the brain responsible for the formation of memories. There they found differences in the electrical activity between the exposed mice and the control group. Exposed mice also had reduced synaptic plasticity — the ability for neurons to make new connections, which is an important component of learning. Scientists also conducted tests to measure both cognition and anxiety. These tests showed that the mice exposed to radiation performed worse in learning and memory tests and displayed increased anxiety-like behaviors.

NASA Goddard Space Flight Center via Flickr

So what does this mean for future Mars missions?

In the original paper, researchers write that this “radiation environment in space will not deter our efforts to travel to Mars.” This is exactly the type of research needed if we are serious about a settlement on the red planet. While we do not have immediate answers to the radiation problem, understanding how it affects brain function is a start. In space travel, and in science in general, there are known unknowns and unknown unknowns. The more unknowns we are able to study here on Earth, the better the chances of humans setting foot on another planet in the foreseeable future.

Good news: Canadian Arctic seals have not been eating plastics

Publishing null results helps us understand where wildlife is safe from plastic ingestion

Photo by Yuriy Rzhemovskiy on Unsplash

Plastics are everywhere. It isn't just humans who are ingesting microplastics on a daily basis, but animals too, such as sea turtles and albatrosses. Plastics can even be found in remote locations, including a high-altitude lake in the Pyrenees mountains in southern France. This increase in plastic pollution prompted researchers to ask: how prevalent is marine plastic pollution, and to what extent is it impacting Arctic wildlife?

But there's good news here for once: a new study out in the Marine Pollution Bulletin found no sign of plastics in the stomachs of 142 seals found in the eastern Canadian Arctic.

Madelaine Bourdages

Seals are an important member of the Arctic marine ecosystem, and act as a vital source of nutrition, cultural and economic value in northern communities. Any plastic ingestion would impact not only the seals, but their surrounding ecosystem and communities too. To investigate whether seals were ingesting and accumulating plastics, researchers collaborated with Inuit hunters to examine the stomach contents of 142 seals found in Arviat, Naujaat, Sanikiluaq, and Iqaluit between 2007 and 2019.

Together, the Inuit hunters and researchers characterized the seals; they determined age, examined tissue pathology, and used sieves to collect plastics >425 μm in size (that's about the size of the period at the end of this sentence!) in the stomach contents for 135 ringed seals (Phoca hispida), six bearded seals (Erignathus barbatus) and one harbour seal (Phoca vitulina).

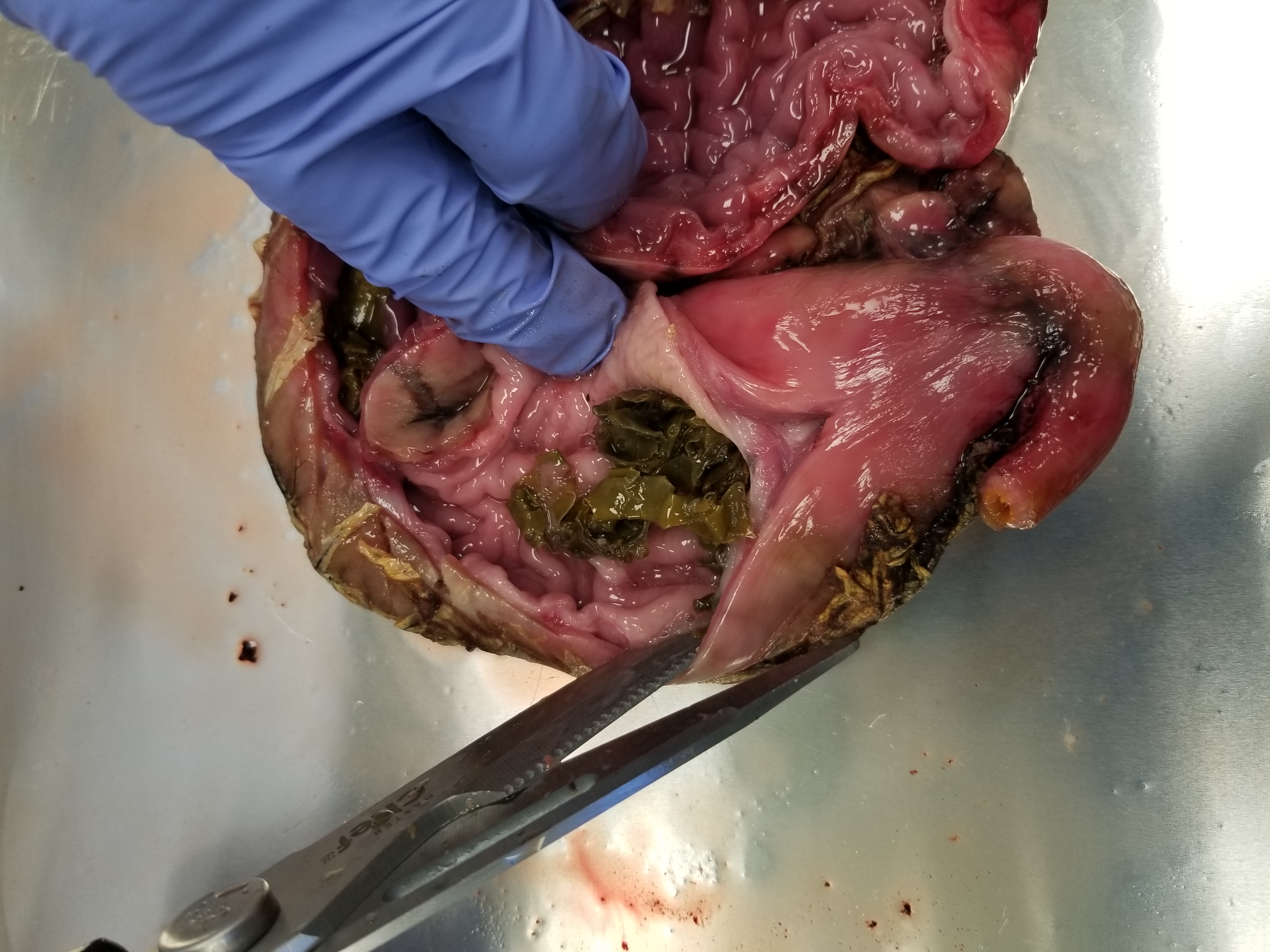

The study found no accumulation of large plastics in the seals examined. Instead, krill or small fish were found in the seal stomachs, with a few containing parasitic roundworms. Around 30 seal stomachs were empty (consistent with other studies), and for 10 stomachs, the contents could not be identified as they were partially digested.

Seal stomach contents.

Madelaine Bourdages

It's worth noting that there may have been microplastics smaller than 425 μm in the seal stomachs. These microplastics wouldn't have been picked up by the sieves, but they also are likely too small to be retained and would have passed straight through the seals' stomachs.

The lead author, Madelaine Bourdages, is a graduate student at Carleton University. Bourdages commented that the results were somewhat surprising given the increase in plastic pollution in the environment, but points out that since “the majority of the seal stomachs contained euphausiids [krill] and fish, [this] suggests that the seals we looked at were likely feeding somewhere in the middle of the water column, and could have potentially been less exposed to larger plastics that typically either float or sink.”

Interestingly, this study is one of the few to report zero plastic ingestion; others include no plastic ingestion found in 134 silver hakes (Merluccius bilinearis) on the Newfoundland south coast, and in Antarctic fur seal scat and albatross stomachs from three islands in the Indian and South Atlantic Oceans. Reporting null results like this study is important — not only to establish a baseline to monitor marine plastic pollution in this particular region, but to better understand where plastic ingestion is and isn't happening.

Instead of climbing into an MRI machine, a new test asks children to just blink

We can now bypass MRIs and instead use trace eyeblink conditioning to measure brain function

By Quinn Dombrowski on Flickr.

The hippocampus is a region in the brain where memories about the space around us and how to navigate it, as well as memories about events that affect our lives are formed. But testing the relationship between the brain and behavior in young children has been challenging in the past, which is why we need novel methods.

Measuring brain function in young children is often challenging because the tools we normally use can intimidate children. For example, a young child may feel scared or restless in an MRI machine, resulting in either unusable data or causing the child to drop out of the study.

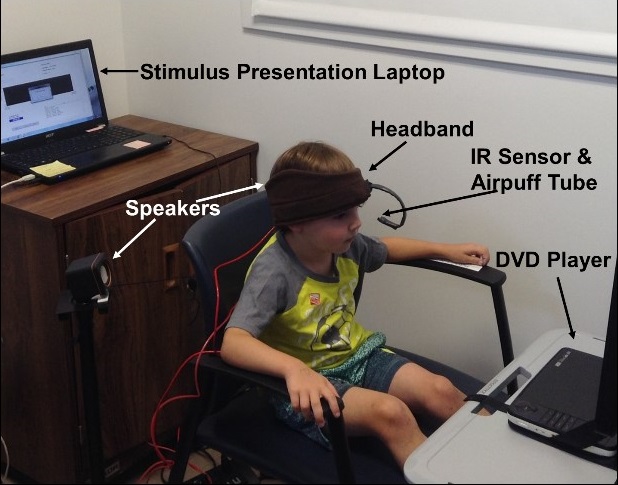

That's why in a study out earlier this year, my fellow researchers and I used trace eyeblink conditioning (EBC) — a novel way to indirectly measure the hippocampal function — to assess spatial and episodic memory abilities in children between the ages of three and six. Because EBC is safe and non-invasive, it is an ideal way to examine learning, memory, and brain function in children.

The trace eyeblink conditioning (EBC) method in action.

Vanessa Vieites

In EBC, children are presented with a series of auditory (i.e., tones) and tactile (i.e. airpuffs to their eye) stimuli. What makes EBC rely on the hippocampus is that the tones and airpuffs are separated in time by 500 milliseconds, and that time lapse, while seemingly insignificant, can be difficult for preschool children to remember. Those who develop a learning response will blink at the sound of the tone alone, thinking that the airpuff will follow shortly.

In our study, we also asked children to take three additional tests. One was a spatial reorientation test, in which they searched for a hidden object in a rectangular room with 3 white walls and one red wall. The second was an episodic memory test, in which they memorized sequences of pictures. Lastly, children completed a processing speed test, which does not rely on the hippocampus.

Children who were better at detecting the predictive nature of the tone were also better at using the geometry of a room to locate a hidden object, regardless of age. These findings suggest that hippocampal function underlies the use of, specifically, geometric strategies for navigating, even in young children.

Newly designed copper nanocubes allow chemists to break down carbon dioxide through a simple chemical reaction

This development should make chemistry and industry a little greener

Photo by Bill Oxford on Unsplash

Using carbon dioxide, a chemical waste, as starting material for chemical transformations has been often proposed as a way to design green chemical reactions. But one problem is that carbon dioxide is a highly stable chemical, which means that its chemical conversion into other products requires harsh treatments, such as the use of high temperature and pressure.

Metal photocatalysis, which is a combination of using light and metals to speed up chemical reactions, could be a solution to address the problem. Ideally, the photocatalyst, a chemical system that absorbs light as a source of energy to initiate a chemical reaction, should be non-toxic, cheap and widely available for this promising technology to find industrial applications. A compound called copper (I) oxide, also called cuprous oxide, seems to be the best fit as it meets current chemical and industrial requirements.

Using carbon dioxide as the basis for chemical reactions, hopefully, will cut down on the amount of this happening around the world

Photo by Diana Parkhouse on Unsplash

However, cuprous oxide can easily undergo other undesired reactions with oxygen atoms and is unstable in water. This is the major drawback for any suitable implementation of metal photocatalysis technology.

Engineers at Nankai University in China, in collaboration with researchers at the University of Toronto in Canada, have now solved this challenge. They used copper nanocubes to convert carbon dioxide into carbon monoxide. The formation of those nanocubes is a relatively simple process, and allowed the team to study the properties of this new material by shining visible light with an intensity 40 times that of the radiation of the sun onto the copper nanocubes. As a result, carbon dioxide (in the presence of hydrogen gas) was successfully transformed into a mixture of CO and water.

This study is a step toward making chemistry and industry more sustainable - and these days, every step toward building a greener world counts.

Questions about biology, sex, and gender? We have answers

Biological essentialism is not based in fact

Sex and gender identity have been in the news, so you, like J.K. Rowling, might be wondering about the difference between sex and gender, or if sex is "real."

First of all, here's a vocabulary review so that we're all on the same page.

Gender identity is our internal sense of who we are (example: woman). It's different from gender expression, which is our external presentation (example: femme). Both of those are different from sex, which refers to our chromosomes, hormones, and genitalia (example: female). With me so far?

Now, sometimes, when people discuss sex and gender, they look to scientific research on these topics. They might end up touting biological essentialism, or the idea that there are two binary sexes (male and female) which ties people to a binary gender identity (man or woman). There's a very fine line, or no line at all, between biological essentialism and transphobia. Biological essentialism is particularly harmful because it makes it seem like there is basis to ignore the existence of intersex or non-binary people, when that's really not the case.

The science is abundantly clear: sex isn't binary. If you want to learn about this in-depth, we have a whole article on it.

But more importantly, scientific research should be irrelevant when it comes to treating people with respect.

In fact, research into the genetic or medical component of stigmatized identities might serve to further biases against marginalized people.

So, before you turn to science to defend transphobia, it's time to re-evaluate your biases.

Reindeers thrive on the Svalbard islands after a century of conservation

Svalbard reindeer were almost hunted to extinction

Svalbard – an archipelago halfway between continental Norway and the North Pole – was discovered in 1596. This discovery proved devastating for the group of islands' wildlife as Svalbard reindeer were hunted extensively and were extirpated from much of the archipelago.

In 1925, the Svalbard reindeer was declared a protected species. Over the course of four summers, Norwegian researchers surveyed this remote archipelago to determine the effects of nearly a century of protection.

What they found was encouraging: the Svalbard reindeer population had reached nearly 22,500 animals, the highest ever recorded and 13 times more than the estimated population in the 1950s.

Researchers also collected and radiocarbon-dated ancient reindeer bones from all over the archipelago. Using the age of the bones and the location in which they had been found, researchers were able to estimate the area occupied by reindeer prior to the arrival of humans on Svalbard. Today, Svalbard reindeer have re-colonized all of their historical territory.

While this is good news for this subpopulation of reindeer, researchers point out that in many other areas of the world, reindeer have not been as lucky. Dramatic declines have been reported in several Canadian provinces (likely related to commercial forestry) and poaching continues to be a major problem in Russia.

Massive's most popular stories from 2019, and the staff's personal favorites

What a year! Let's relax for a bit

In 2019, Massive Science covered some ground. We wrote about climate change killing off biodiversity, galaxies eating one another, parakeet mate selection, and on and on. We polled the Massive staff for their favorite stories of the year, both in what we worked on and in the outside world. But first, our top five most popular articles of the year:

#5

After another devastating intergovernmental report on wildlife loss, Cassie Freund wrote this urgent call for action. It's the very real end of the world, why isn't anyone acting?

#4

Neuroscience is Massive's bread-and-butter, so Claudia Lopez-Lloreda's story on fish giving up and the brain cells responsible checked a lot of boxes. Next time you quit on something, you'll know who's at fault.

#3

"Unexpected science" is another angle our writers have gotten serious mileage out of, and Darcy Shapiro's article on gorilla teeth, snacks, and how that changes human history is a classic of the genre.

#2

Definitely another "unexpected science" entry, Molly Sargen's story combined math, bridge building, and breakfast food. Now we know our audience likes that and more breakfast food science will be coming in 2020.

#1

It's got it all: space and a vague sex angle. What more could you want? You might say that Mackenzie Thornbury's article went viral. We won't though.

Sometimes though, what we think is cool and what you all think is cool doesn't match up. We're not mad about though, we know disagreement is natural. Not mad at all. Here are our personal faves that we think you should give a second shot. No pressure though!

Or, as it was more affectionately known in the Slack channel: Babies...in...SPAAAAAAACE.

Another Cassie Freund work on the actual human effort to get around conservation efforts that other humans are employing to save the planet.

"Connecting brains" is a sub-genre of our normal neuroscience work and Jordan Harrod wrote one of the best ones we've ever seen.

Yeah, the science is cool, the writing is great, but you know what really spiced up Luyi Cheng's debut article? The gifs.

We love all Our Science Heroes equally, but there's something about du Châtelet. If a man had had her adventurous, influential life that included standing on Newton's shoulders and having Voltaire as a kept man, there'd be movies made about that man's life. This is our pitch for a du Châtelet biopic. Hollywood, please call us.

How 14 months in Antarctica changes your brain

Studying the effects of isolated, monotonous environments on the human brain has important implications for space travel

Photo by Cassie Matias on Unsplash

In a short correspondence published in the New England Journal of Medicine, neuroscientists studied the brains of polar researchers. The nine scientists lived in Antarctica for a span of 14 long months, enduring isolation and extreme environmental conditions. The neuroscientists used magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to take pictures of the explorers’ brains and measure the volume of different areas before, during and after the expedition. When they compared the before and after scans, they found that certain brains areas became smaller in the explorers subjected to these extreme conditions compared to controls.

Of particular interest was the hippocampus, an important area for learning and memory. They found that a specific area of the hippocampus called the dentate gyrus seemed to be especially vulnerable to the Antarctic environment, with the most substantial decrease. The polar researchers also had lower levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor — a protein that is important for neurogenesis — and worse performance on tests of spatial abilities. The authors say that these data should be taken with a grain of salt since only nine explorers were studied and it's unclear exactly which of the elements of the Antarctic mission contributed to these changes in brain structure and function. Was it being limited to interacting with the same small group of people for more than a year? Or living in a monotonous environment? Or stress? Or poor sleep? These questions can only be answered with more research.

Celebrating the Periodic Table of Elements

A chance to look back on accomplishments but also consider our planet's future.

The first recognized periodic table of elements was published 150 years ago by Dmitri Mendeleev and has been heralded as one of the most important scientific achievements in chemistry. It is also important in biology, physics, medicine and earth sciences; it is a universal language connecting students, teachers and researchers from all over the world.

That is why the United Nations General Assembly and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) proclaimed 2019 the International Year of the Periodic Table of Chemical Elements (IYPT2019), holding conferences and symposiums in different countries and a closing ceremony in Tokyo. This is an opportunity to celebrate scientific achievements as well as the elements themselves — the Nobelium contest asked people to submit educational videos, stories, poems, songs, and art about the periodic table or individual elements.

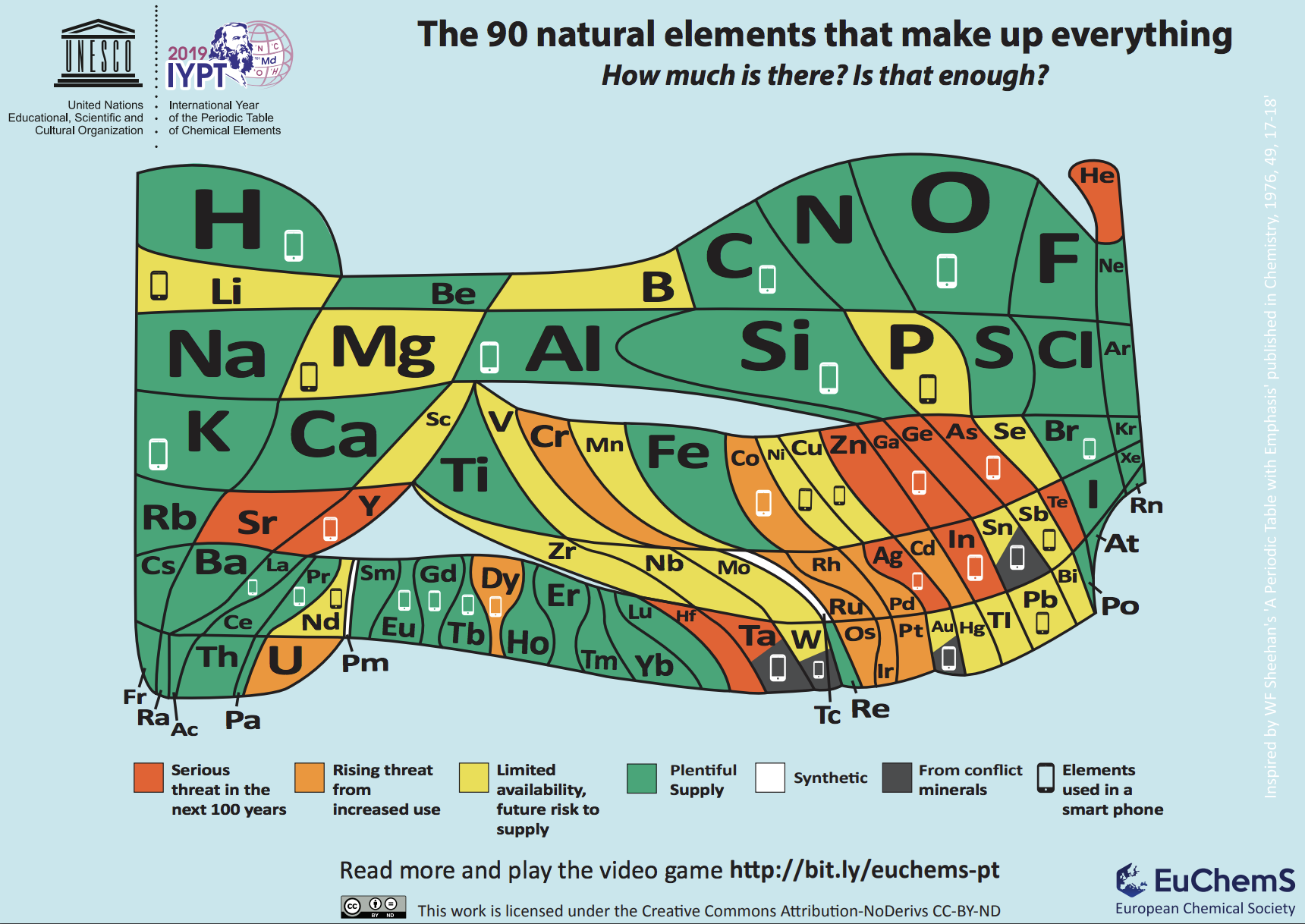

But it is also a chance to consider the availability of resources needed by a growing global population.

European Chemical Society

To highlight this, the European Chemical Society (EuChemS) designed a quantitative periodic table in which the area of each element is proportional to its abundance (in a logarithmic scale) in earth’s crust and atmosphere which is color-coded to represent how long each element will last if we continue to use it at the current rate. Some elements are of more concern than others because they are naturally less abundant in earth’s crust or they come from conflict minerals or they are not easy to recycle. Elements’ supply is especially threatened by their intensive use in devices like laptops, tablets, and smartphones. Examples of elements of concern include indium, which is part of the transparent indium tin oxide (ITO) layer of touch screens and tantalum, present in microcapacitors and which can come from the conflict mineral coltan. Both indium and tantalum have a recycling rate of less than 1% and considering the huge number of smartphones (it's estimated that there are nearly 3 billion smartphone users worldwide) - significant quantities of these elements are being lost.

Celebrating the periodic table has therefore become a call to preserve our earth’s precious resources and to live in a more sustainable way, by reducing the amount that we consume, repairing, reusing and properly recycling: this is how we can continue to enjoy our wonderful planet for generations to come.

Researchers find four new drug candidates to tackle Huntington's disease

There is currently no approved treatment for the reversal of Huntington's disease

GerryShaw on Wikimedia Commons

Huntington's disease is an inherited neurodegenerative disorder which leads to the progressive deterioration of movement, cognition and behavior. In the US, 30,000 people are living with Huntington's disease, and another 200,000 individuals are at risk, where symptoms can start at any point between childhood to advanced age. While approaches such as speech and physical therapy, antidepressants and antipsychotics have been adopted to slowing down disease progression, there is currently no approved treatment for the reversal of the disease. Recently, a drug has entered clinical trials and results are awaited with bated breath.

In the human body, misfolded or dysfunctional proteins are engulfed by structures called autophagosomes, which target such proteins for degradation via a pathway called autophagy. Here, Huntington's disease is caused by a mutation in the HTT gene, which encodes a protein called Huntingtin (HTT). This mutation allows the HTT protein to escape autophagy, and instead accumulate and destroy neuronal cells found in the brain over a period of 10-25 years.

In a recent study published in Nature, researchers have identified four synthetic organic compounds which link the mutant HTT to a protein called LC3 which is present on autophagosomes, thereby ensuring the removal of the mutant HTT by autophagy.

These four compounds lowered the levels of the mutant HTT protein by approximately 30% in comparison to normal HTT, when tested in different mediums — specifically in vivo in Drosophila fly and mice models of Huntington's disease, and in vitro on cultured neuronal cells obtained from mice and individuals with Huntington's disease.

In addition, these compounds are specific for the mutated portion of the Huntingtin protein as they could potentially attack another similarly mutated protein called Ataxin-3, which happens to cause spinocerebellar ataxia — an incurable neurodegenerative disease. The compounds were even capable of reversing the disease symptoms in both Drosophila flies and mice. Here, the affected flies and mice on treatment with the compounds displayed significant improvement in behavioral and movement deficits measured by tests such as whether the Drosophila could fly, and how well mice were able to balance and display gripping force.

These four synthetic compounds serve as promising candidates for future drug discovery research in this field. The study also opens the field for targeting several proteins which accumulate the same kind of mutation, leading to severe neurodegenerative disorders.

Lake Victoria, world's largest tropical lake, may be drying up faster than we thought

The shrinking of Lake Victoria could have devastating consequences for the 40 million people in the region

Today, populations around Lake Victoria and downriver rely on its freshwater for agriculture, fisheries, and hydropower. It's an ecologic and economic backbone for the region. But we know from cores of ancient lake sediments that this hasn't always been the case. In fact, it has dried out and refilled as recently as 14 to 18 thousand years ago.

Now, the question researchers are trying to answer is: how long do we have until it dries up again?

A new study, published in Earth and Planetary Science Letters, indicates that we may have less time than previously thought.

Researchers have developed a new hydrologic model that shows that Lake Victoria's outlet to the White Nile (one of the two major tributaries of the Nile River) could be dry within a decade. Kenya could completely lose access to the lake in less than 400 years.

Based on ancient lake records, the dry periods are due to a combination of the region getting less rain and evaporating water more quickly, both of which are connected to higher temperatures. Climate change, as currently projected by the IPCC, could aggravate these factors and accelerate the drying of Lake Victoria. Predictive hydrologic models like this can allow regions to prepare for water-stressed conditions and economic repercussions.

This dire prediction highlights the need for a global response to lessen the effects of climate change, before the White Nile goes dry.

New study finds that too much screen time can alter children's brains

WHO guidelines state that children between 3-4 years old should spend no more than one hour per day looking at a screen

Washington Heritage Collection - Work and Industry, via Flickr

Young children these days are exposed to more screen time than any generation previously. Not only are they exposed to traditional media technology such as the television, but access to newer technologies such as hand-held tablet devices means that screen time has become an integral part of growing up in today’s society.

In April of this year, a World Health Organization report recommended that children between the ages of 3-4 years old should have no more than 1 hour of sedentary screen time per day. Now, emerging evidence is suggesting that excessive screen time can have detrimental neurological effects on young children. A recent study published in JAMA Pediatrics utilized an MRI technique called diffusion tensor imaging alongside a survey to assess a child’s screen time.

The study authors found that in healthy children between the ages of 3-5, children who had greater than one hour of screen time per day had decreased integrity of their white matter in tracts that support language, literacy and executive functioning. These trends persisted even after controlling for child age and household income. This suggests that early screen use may impair early brain function and development, and supports the recommendations made by the World Health Organization earlier this year.

Forget baby shark: grandma whale, the real hero of the ocean, is looking after her grandkids

New research shows that grandmother orcas greatly improve the survival of their grand-offspring, advancing our understanding of the evolutionary role of menopause

NOAA/Robert Pittman on Wikimedia Commons

The phenomenon of menopause has long confounded biologists. From a strictly evolutionary perspective, the life goal of any living thing is to survive long enough to reproduce and pass on its genes to a new generation. So understanding why some animals, including humans, live long beyond they are able to reproduce has been puzzling.

One hypothesis for why menopause has persisted is called the "grandmother effect." Female animals (and humans) who live long enough to see their children have children are thought to earn additional evolutionary currency by helping their grandchildren, who carry 25% of grandma's genes, survive — a concept called inclusive fitness. There is some evidence that the grandmother effect is a factor in why humans are so long-lived, but we are still learning whether this is true for other animals.

Now, a new paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences establishes strong evidence for the grandmother effect in orcas, colloquially known as killer whales. Orcas live in female-led, or matrilineal, societies and travel in tightly-knit family groups. Using a 30-year dataset comprised of photographs of two groups of killer whales and long-term observations of their behavior, they found that the support of grandmothers substantially increased survival of their grand-offspring. Given average values of salmon abundance (a key food source for these two groups of orcas), young whales who lost their maternal grandmother within the past two years were 4.5 times more likely to die than a young whale with a living maternal grandmother. This is because grandmothers help provide safety and food to the young whales, and teach them how to make their way in the world.

This study, combined with previous findings about the reproductive costs incurred by both mother and grandmother whales when they are both raising children at the same time (an effect that this study was able to replicate), tells us a great deal about the evolutionary rationale for menopause. Grandmotherly support is key for long-lived organisms, like us and our whale cousins, to raise our young, and this effect is so powerful that it may have enabled us to live into our nineties and beyond. So next time you see her, give your grandma (or someone else's!) an extra big hug.

Your Apple smartwatch may be the key to detecting heart issues before they happen

Researchers surveyed over 400,000 participants over eight months to see whether a smartwatch app could detect atrial fibrillation

By Robina Weermeijer on Unsplash.

In an era where Internet-connected devices can measure your pulse, the ability of these smartphone devices to identify cardiac diseases is still unknown — and presents an untapped potential. More than half a million people in the United States are unaware they suffer from cardiac disorders, such as atrial fibrillation. This condition, in which the heart beats irregularly, increases the risk of suffering a stroke by five times, and could even lead to heart failure. But can an app in your smartwatch detect it?

Researchers set out to investigate if a notification algorithm in an Apple Watch application was capable of identifying atrial fibrillation. In the Apple Heart Study, participants used a smartwatch app to monitor for irregular pulses during an average of 117 days. In the study, participants that received an irregular pulse notification from the app — which may be possible atrial fibrillation — were asked to start a e-health consult through the app and received, via the mail, an electrocardiogram-patch to wear at home for up to a week to confirm the disorder.

Atrial fibrillation was confirmed in 34% of the participants who received irregular pulse notifications by the app and completed the electrocardiograms. Overall, the chance of getting an irregular pulse notification while suffering from this cardiac disease at the same time was 84%.

Even though detection technologies are rapidly advancing, additional studies are still necessary to further develop notification algorithms in smartwatches as reliable tools for disease diagnosis. People who experience atrial fibrillation symptoms, such as racing heartbeats, shortness of breath, or chest pain, should still pay a visit to the doctor.