Science in HD via Unsplash

Titanium studded with silver and copper makes harvesting energy from the Sun more efficient

Incorporating metal ions into titanium dioxide creates better semi-conductor plasmonics

Our dependence on fossil fuels has resulted in detrimental effects to the planet and the environment, most notably high carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions, a major contributor to climate change.

How can we free ourselves from fossil fuels?

The Sun.

The Sun is a near-endless source of energy for our planet. Organisms have been exploiting solar energy for billions of years.

Now we can one-up photosynthesis. The development of solar energy-based artificial systems, or photocatalysts, as materials that mimic plants in their ability to capture solar energy has sparked great research interest across academia and R&D. As part of a research team at the University of Alberta, I have had the chance to collaborate in the development of a similar photocatalytic system, a plasmonic bimetal semiconductor photocatalyst, with great promise to convert CO2 into sustainable, green fuels.

A material’s ability to conduct electricity is dependent on the density of electrons within it. In this aspect, semiconductors are middle-ground materials compared to metals and insulators. Metals have a sea of electrons that flow freely between atoms, making them excellent conductors. Insulators are the exact opposite. The picture is quite different in semiconductors where electrons occupy two specific energy levels: valence and conduction, which are separated by an energy gap. Electrons from the valence level can hop to the conduction level when the semiconductor absorbs enough energy to jump the gap. The movement of the negatively charged electrons leaves behind positively charged holes in the valence level. These electrons and holes can then be utilized to promote chemical reactions.

Titanium dioxide (TiO2), commonly found in sunscreens, coatings (like non-stick cooking pans), and cosmetics, is an ideal material for a semiconductor photocatalyst. Being a low-cost alternative that is not only highly available but is of low toxicity, stable in acidic and basic environments, and corrosion resistant, TiO2 is already a popular artificial photocatalyst that has been used for hydrogen fuel generation, wastewater treatment, air purification, etc. Despite all these benefits, large scale commercialization of semiconductor photocatalyst technology has been slow.

Most semiconductors, including TiO2, primarily absorb UV light, which is only 4% of the solar energy spectrum. This means we are only tapping a sliver of the full bandwidth of the Sun's energy. On top of that, most semiconductors suffer from low harvesting efficiencies as electrons and holes do not flow effectively within the material and ultimately dissipate. To overcome these hurdles, we embedded metal nanoparticles within semiconductor photocatalysts. This composite system generates highly energetic charge carriers or “hot” electrons to enhance photocatalytic activity.

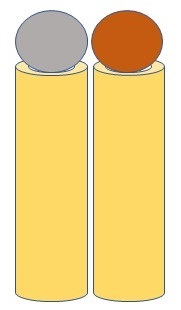

A diagram showing silver (gray) and copper (red) nanoparticles arranged next to each other in a plasmonic as "neighbors"

Ajay Peter Manuel

When light shines on a metal nanoparticle, the electric field pushes electrons toward one side, resulting in an accumulation of negative and positive charges on either end of the nanoparticle, an arrangement called a dipole. Opposites attract, so these collections of positive and negative charges attract one another, leading to waves of charges oscillating like a pendulum within the metal nanoparticle. Like tuning a musical instrument, if we match the frequency of the light shining on the nanoparticle to the frequency of the charge oscillations in the metal nanoparticle, a resonance can be created resulting in a high density of hot electrons. This combination of light energy with the charged particle soup in the metal nanoparticle is called a plasmon, giving the resultant composite system its name: a plasmonic photocatalyst.

We capitalized on the advantages of a plasmonic photocatalyst by incorporating silver (Ag) and copper (Cu) nanoparticles in TiO2 nanotubes. Ag and Cu have strong resonances in the visible-infrared spectrum of light — where the frequency of the charge oscillations in the metals matches the frequency of visible-infrared light — which accounts for about 95% of the light we get from the Sun. The presence of metal nanoparticles also allows for improved separation of electrons and holes and provides favorable sites for reactions to take place on the surface of the photocatalyst. The resultant system is a plasmonic bimetal (AgCu) semiconductor (TiO2) photocatalyst.

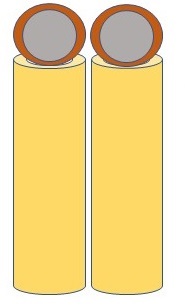

A diagram showing silver (gray) and copper (red) nanoparticles arranged with silver in a core surrounded by copper ions

Ajay Peter Manuel

This AgCu-TiO2 system outperformed previously reported photocatalysts in converting CO2 into clean fuels such as ethane, which has a much lower global warming impact compared to other fuels, with an efficiency of 60.7 percent. In comparison, ethane production with TiO2 photocatalysts alone, without metal nanoparticles, is a daunting obstacle. The success of the AgCu-TiO2 system can be attributed to multiple asymmetric dipoles, where we have a mixed, as opposed to a positive only and negative only, collection of charges on either ends of the nanoparticles, that form a collection of resonances promoting the transformation of CO2 into ethane. These asymmetric dipoles allow for CO2 molecules to attach easily onto the photocatalyst's surface. The generation of hot electrons and holes via the resonances of Ag and Cu also offset the high energy demands for ethane production and further enhance the process. This is facilitated by the Ag and Cu nanoparticles being arranged in differing architectures as neighboring or core (Ag)-shell (Cu) nanoparticles.

These results demonstrate the potential of bimetallic plasmonic photocatalysts in replacing traditional photocatalysts as a crucial technology for CO2 photoreduction. Nevertheless, there remains much to be understood about the fundamental physics behind plasmonic phenomena, specifically the dynamics of hot electrons and holes. The obvious next step would be to continually improve CO2 product selectivity and yield. Cheaper metal nanoparticle combinations apart from AgCu and diverse architectures of semiconductor photocatalysts must also be considered. Plasmonic photocatalysis, as a field, may be in its infancy but it is ripe with exotic possibilities and innovative solutions enabled by the use of noble metal nanoparticles toward tackling diverse, macroscopic problems.