Produced in partnership with NPR Scicommers

Don't feed the bears. It shortens their telomeres

Bears that get food from humans hibernate less, which has molecular repercussions

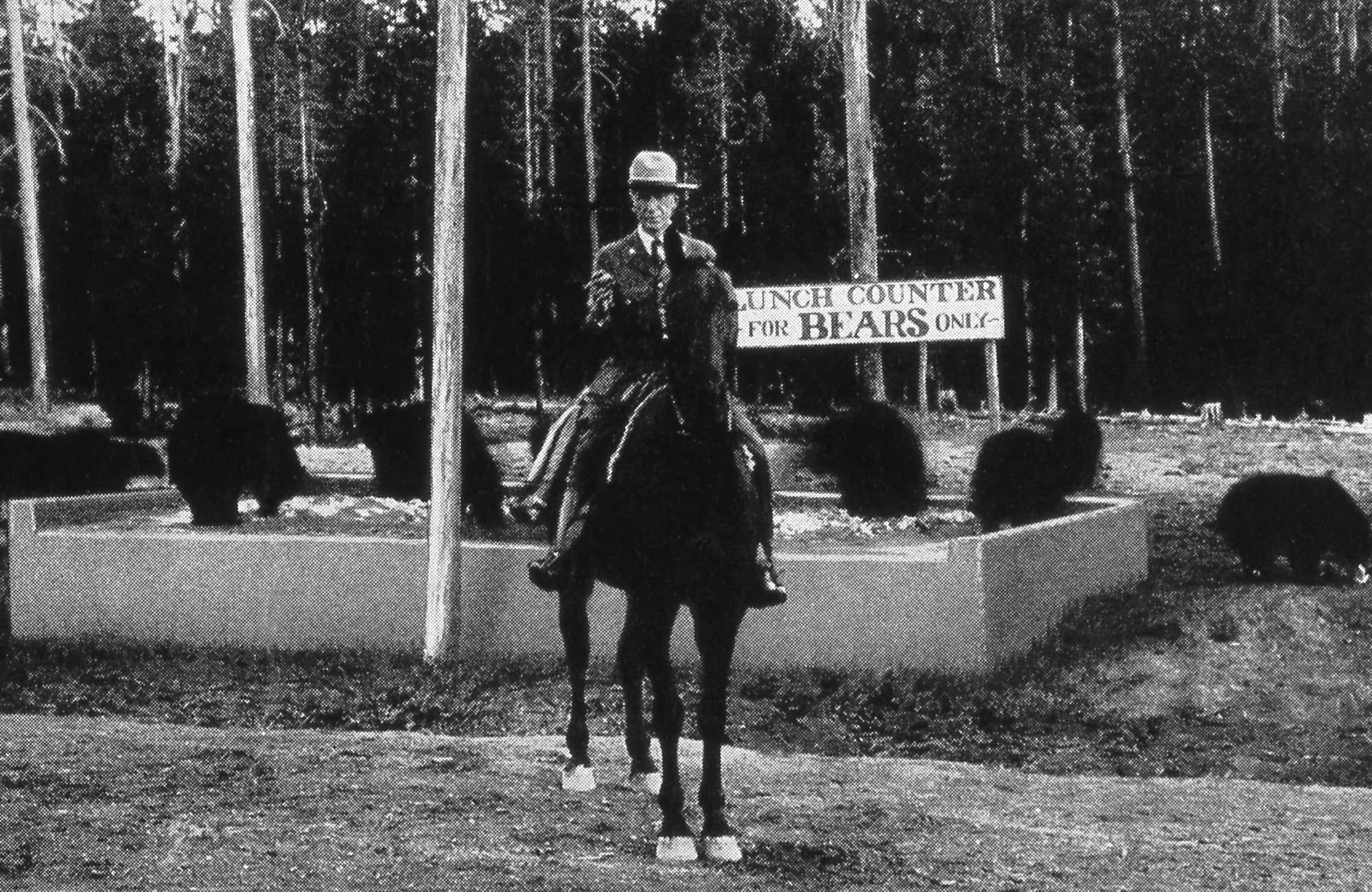

“Lunch Counter for Bears Only” reads a sign standing over a dump in a 1920s photo of Yellowstone National Park. Photos and videos from the era show dozens of black bears swarming mounds of garbage and kitchen scraps provided by the Parks Service at the Old Faithful bear feeding ground. Thousands of tourists packed into grandstands to watch nightly “bear shows.” Cars, backed up along park roads, were filled with visitors snapping photos and holding food scraps out the window for begging bears.

Although early images portray a quaint picture of interspecies civility, nearly 50 people a year were bitten or mauled by bears in Yellowstone before a ban on feeding wildlife was put in place by park administration in the 1970s. But park visitors weren’t the only ones harmed. Bears that terrorized campgrounds and attacked visitors were killed by park authorities, and roadside beggars were often struck by cars. Now, beyond conflict with humans, recent research has revealed that our food has striking ecological and even molecular consequences for wildlife as well.

In Durango, Colorado, wildlife biologists Dr. Rebecca Kirby and Dr. Heather E. Johnson researched the impact of human food on American black bear behavior. “Our findings highlight how human food subsidies can indirectly influence changes in aging at the molecular level,” Kirby writes, “We found that bears that foraged more on human foods hibernated for shorter periods of time.”

NPS

Hibernation represents a time of repair and recovery for many mammals. It allows them to survive periods of food shortage and harsh environmental conditions. “Hibernation is an adaptation to deal with seasonal food limitation,” Johnson says, “but if a bear still has food available it doesn't necessarily need to hibernate.”

The substantial amount of human food available to black bears has led to delayed and shortened hibernation periods. “Researchers working in Tahoe have reported that some bears there don't hibernate anymore, given the year-round access to human foods,” Johnson noted. However, hibernation not only allows the animal to survive challenging conditions, but as researchers found, it may also “slow cellular aging” by defending the protective ends of chromosomes (telomeres) against erosion.

Telomeres are DNA sequences at the ends of each chromosome that do not encode proteins, but protect the coding sequences when the cell replicates. The length of an animal’s telomeres is a strong predictor of survival and longevity. Shorter telomeres reflect damaged DNA or a greater number of cell replications, caused by age or disease.

Three black bear cubs by cars, one is climbing on a car.

The researchers in Colorado collected hair and blood samples from immobilized bears and found that those that fed on human food delayed hibernation and, as a result, had shorter telomeres. “Recent studies have found that more time spent in [hibernation] can [slow down telomere shortening],” says Kirby. But bears that feast on human food “experience greater cellular aging” and “lose some of the long-term fitness advantages associated with hibernating.”

Decreased fitness means fewer offspring and declining populations – and losing bears could have catastrophic downstream effects on ecosystems. As omnivores, bears occupy a critical niche, controlling the density, distribution and behavior of species lower on the food chain. In Durango, Colorado, a black bear’s diet primarily consists of “grasses and [flowering plants] during the late spring and early summer, and then switches to berries, nuts, and insects later in the summer and fall,” says Johnson.

Yellowstone National Park, circa 1950s

Through their omnivorous diet, bears contribute to seed dispersal, insect population control, and nutrient cycling – vital components of a healthy ecosystem. Bears also mediate the behavior of smaller predators through fear, keeping them from overfeeding on other organisms in the environment. Like breaking a single strand of a spider web, when one element of an ecosystem is impacted the reverberations are felt throughout the system. If bear populations decline, smaller predators can become emboldened and overfeed, which will cause their food species to be diminished. This effect (called a “trophic cascade”) ripples throughout ecosystems, restructuring them and often leaving them with only a few remaining species.

But animals don’t have physically vanish from an environment to be removed from their ecological role. Another study investigated the impact of human food on wildlife by observing wolves in the National Park of Abruzzo in Italy’s central Apennine Mountains. They found that the availability of free-ranging livestock in the park depressed the “predatory behavior in wolves” despite an “abundant wild prey community.” Farmers, faced with challenging and remote terrain, often abandoned the carcasses of livestock that died in the mountains.

Consequently, wolves altered their behavior, choosing to scavenge deceased livestock rather than hunt live prey. Although the livestock remains were not provided intentionally, they reduced the wolves’ “ecological role,” the study found, which included keeping wild boar or deer populations in check through “top-down effects” like predation. Even though wolves were present, they were no longer acting as apex predators – species pivotal for maintaining the structure and diversity of an ecosystem – which opened up the park to the possibility of devastating trophic cascades.

While we’re a far cry from the “bear shows” of Yellowstone past, we still (sometimes even intentionally) subsidize wild animal diets with our food. Tourism companies attract bears to tour routes using human food. Farmers with free-ranging livestock provide subsidies for many native predators. Hunters bait prey with junk food to habituate them. Landfills provide scavenging birds with so much sustenance that they forego migration. And our bad habit of feeding wildlife creates risks for both people and animals as Heather Johnson has seen in Colorado: “For people, this means more human-bear conflicts, with increases in nuisance behavior, property damage and threats to public safety. For bears, this means greater risk of injury and mortality, as bears that forage within developed landscapes are more likely to be hit by cars and lethally removed by landowners or agencies.”

We’re beginning to understand the more nuanced effects of our food on wildlife. Through the provision of food subsidies, we’re effectively restructuring ecosystems, often leaving them less functional than when we found them. “Leave no trace” – the concept of limiting our environmental impact while recreating outdoors – is beginning to take on an entirely new meaning as the molecular and ecological consequences of our food on wildlife comes into focus.