Photo by averie woodard on Unsplash

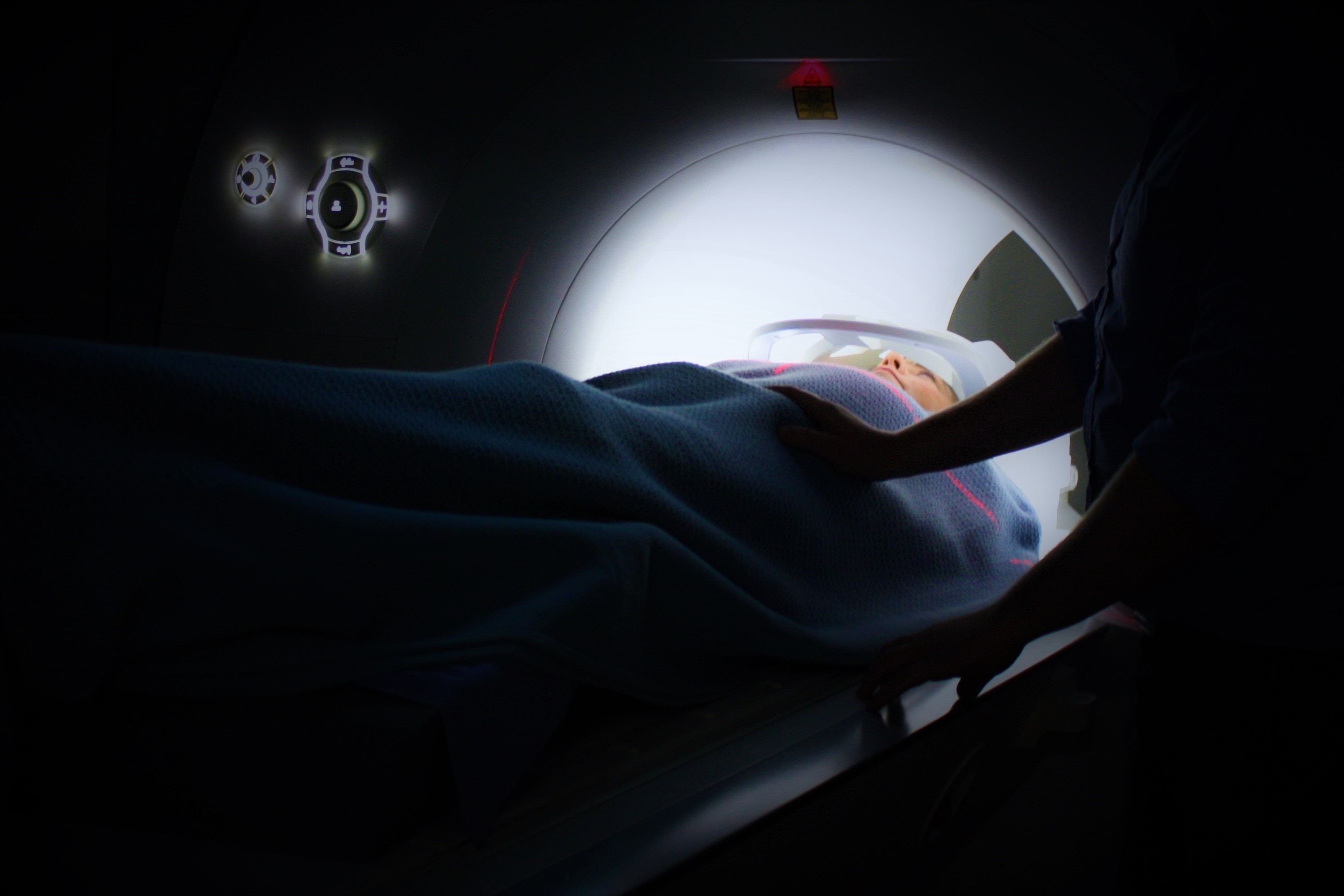

Neuroscience should take sex differences in the brain more seriously

Diseases like Alzheimer's and schizophrenia manifest differently in men and women, and that's important to know

As a neuroscientist who identifies as a woman, I love that there is discussion of dismantling the patriarchy and supporting diversity for those working in STEM. But, as a neuroscientist who studied the neurobiology of postpartum depression and how hormones affect the brain, there’s another layer to the issue of sexism in the field that we have to talk about: diversifying our research subject pools.

Neuroscience has historically had a problem of predominantly using male test subjects, from studies of how the brain works to what happens in brain illnesses. The field then assumes that whatever has been true for them will be true for everyone else. This assumption is dangerous.

Take the drug zolpidem (trade name: Ambien) to treat insomnia. When the medication was first released in 1992, doctors provided men and women with prescriptions of equal doses of zolpidem, and hoped that this would alleviate their sleep troubles. But, no such luck... for women. Women began reporting adverse effects ranging from hallucinations to sensory distortions because the drug was not clearing out as quickly from their bodies. In 2010, women accounted for 68% of ER visits related to zolpidem. Researchers are still not entirely sure why women are more sensitive to it; hypotheses range from differences in how men and women's liver enzymes work, body weight differences, and even testosterone levels. Nonetheless, the FDA now recommends that women should be prescribed smaller doses than men.

Similar issues have come up with different responses to antidepressants, identifying symptoms of autism, and understanding how Alzheimer's disease happens.

Some medications, like Ambien, affect men and women differently

Photo by freestocks.org on Unsplash

But, the bigger question is why did it take women struggling before researchers realized that sex differences exist in the first place?

Before we answer that question, we have to talk about what sex differences are. Sex refers to the biological condition of one’s sex chromosomes, with XY generally classified as male, XX as female, and expressions like XO or XXY as intersex (XX or XY individuals can be intersex as well). Gender refers to how one identifies and is influenced by societal and cultural factors. Sex differences in the brain refer to when features of the brain — like chemical levels, hormone receptors, or immune activity — are present in everyone, but biological sex influences how much they are present. For example, sex chromosomes affect production of hormones like testosterone and estrogens. Everyone has different levels of both hormones which can affect all organs of the body, including the brain. It’s not only hormone levels, either. There are sex differences in how the brain processes the stress response, activity of chemicals like dopamine and serotonin, and even how the immune system interacts with the brain.

Biological sex affects many aspects of how our brains work

Photo by Ken Treloar on Unsplash

And yet, neuroscience has long evaded including a diverse group of participants, members of all sexes, in experiments.

A 2017 study on sex bias in neuroscience research analyzed leading journals in the field and found that for rat and mice models, which account for approximately 50% of neuroscience research, the majority failed to use biological sex as a statistical variable or acknowledge the sex of the animal. Omitting sex as a variable in data analysis means that valuable information about whether a discovery was relevant or not to a particular sex gets lost. Failing to report the biological sex of the subjects creates chaos in trying to replicate and build upon findings. And casually discarding data should bother everyone.

Considering biological sex as a factor in research has been revelatory for understanding the brain. Neurological and psychiatric conditions such as autism, Alzheimer’s disease, schizophrenia, depression, and Parkinson’s disease are characterized by sex differences in the prevalence of the disease, how if manifests, and even how effective treatments are. In my own research, I've studied depression, an illness that affects twice as many females as males, with particular vulnerability around times of hormone shifts like puberty and pregnancy. Using a rat model of postpartum depression, I found that after the huge hormone changes of pregnancy and postpartum, traditional antidepressants weren’t as effective in the brain, a concern for the 15% of mothers struggling with postpartum depression.

But, there is understandable concern about how academic institutions and their deeply rooted misogyny will use this information. Will differences be exploited as biological proof one group is better than the other? More capable than the other? Will differences be used to categorize what’s “normal” and consequently discriminate other groups as “abnormal”?

Considering biological sex as a factor in research has been revelatory for understanding the brain

These fears have sparked a counter-argument, calling for researchers to abandon studying sex differences in the brain. Researchers like Gina Rippon, a professor in cognitive neuroscience at Aston University in the UK, claim that researching sex differences is a form of “neurosexism” and that the evidence of biological sex affecting the brain is a “myth.” Not only is this problematic because it undermines the growing body of evidence that researchers have been conducting to rectify the historical sex bias in neuroscience research, it creates confusion for how today's neuroscientists fix the problems of the past. And it does so by conflating equality with conformity, aka to treat everyone as “equal” means they must all be “identical to men.”

I understand why their fears exist. Oppressors have long distorted neuroscience to fit their claims of superiority and use it as means to justify oppression. And shamefully, it’s not even that old of a problem. The infamous 2017 Google memo claimed that sex differences in the brain meant women were biologically incapable of being equal to men in performing in the technology sector. Only last year, a professor from the European Organization for Nuclear Research, or CERN, argued that women’s brains were fundamentally inferior in studying physics as an explanation for why there are fewer women physicists relative to men. They brushed off gender inequality in their fields as the nature of the oppressed rather than systematic barriers nurtured by the oppressors.

This fear is also relevant to the LGBTQIA+ community. Sex and gender are more complex than “male” and “female” (check out this infographic from Scientific American). Biological sex is often assigned based on what the gonads look like at birth, not necessarily based on genetics. So, intersex conditions may not become apparent until later in life. Neuroscience research has been informative for sensory function during gender confirmation surgeries. But, biomedical research has historically been conducted to further marginalize those who don’t identify with their sex assigned at birth or conform to heteronormative conditions. Fear that neuroscience research will be used to further isolate them, or worse, treat their identities as deviations from a false dichotomy of “male” or “female” is anti-scientific.

The questions that plague neuroscience research — How can we cure neurological and psychiatric disease? Why aren’t the current drugs working? — are questions that demand more data. Turning a blind eye to how sex and gender affect the brain as a solution to sexist interpretations of data is akin to pretending to not see people of color as a solution to racism. Does it conveniently allow for those in power to sweep marginalized groups under the rug and call it equality? Yep. Does it actually fix the problem of inequitable research? Nope.

Studying the brain is a messy, but necessary, endeavor

Photo by jesse orrico on Unsplash

There also is an argument that researchers should abandon studying sex differences because gender is more influential than biological sex in the human brain, stemming from confusion about “nature” vs. “nurture” in the brain. Nature refers to things that are usually present before we’re born, like sex chromosomes, whereas nurture refers to things we encounter as we grow up, like sociocultural influences around gender. The brain is tremendously plastic, with connections rewiring moment to moment. Both biology and environment influence how plasticity happens in the brain, not simply one or the other.

Here’s the truth: studying the brain is messy. It’s messy because literally everything — from DNA to culture to gender to your childhood — affects how it works. Parsing out these differences seems messy but actually provides a more nuanced and accurate understanding of the brain. As feminists and neuroscientists, we must work towards the ideal of equitable research so that everyone benefits from neuroscience. Studying sex differences isn’t the magical last step to solving the mysteries of the brain, but it is a part of the puzzle that is valuable.

We’re all different. And those differences aren’t going away by blindfolding the data to those differences.

Great piece Aarthi! Super appreciate the external link that you provided from Scientific American.

The issue you bring up is a general issue within a lot of scientific research right now. The NIH thankfully makes it a requirement now that you include both sexes in all preclinical studies. I am super intrigued by the point you brought up with regards to the sex differences in neurological and psychiatric conditions. It really seems that the sex differences in these conditions have been the main driving point to really start considering sex differences in other health conditions. I recently reviewed the literature with regards to the sexual dimorphism of the placenta, and many of the papers I came upon had as their rationale the sex differences in neurological and psychiatric conditions in humans. It seems that even in the case of placental development and function, sex differences are KEY. The literature was supporting the idea that the placenta produces sexually dimorphic responses to intrauterine stress exposure which leads to differences in neurodevelopment in the fetus. And thus, possibly explaining the differences in disease prevalence. Thanks for this!