Boobies of the Galápagos are replacing their disappearing food source with junk fish

Decades of research show how the sardine's decline threatens an entire ecosystem

No hot shower? Sleeping in a tent on the ground? No fresh veggies, alcohol, or even – gasp – ice cream, for three months straight? For some, this might sound miserable. But in 2011, I eagerly jumped at the opportunity to live with four other biologists on an uninhabited island in the Galápagos Archipelago off Ecuador, all for the sake of studying boobies. Nazca boobies, that is: a brilliant white seabird with black wing tips and a salmon-colored bill that forages for fish hundreds of kilometers over the Pacific Ocean.

Like many species in the Galápagos Islands, Nazca boobies have a certain naiveté, or “tameness,” to humans – they don't leave the nest or respond to disturbance as many other bird species might. This has allowed researchers at Wake Forest University to track the same individuals over many years, some across their entire lifespan, without having negative effects on the individual or the population. Requiring incredible dedication and planning, the long-term project studying Nazca boobies on Isla Española, Galápagos, just entered its 35th year. Only through this long-term approach were scientists able to detect that climate change could cause a stable seabird population to decline.

Booby are what booby eat

A study published in August 2017 was the culmination of over 30 years of data from many field assistants, graduate students, and project leader, behavioral ecologist David J. Anderson (I'm now a PhD candidate in his lab). Dave has collected diet samples from Nazca boobies at Punta Cevallos, Isla Española since he started his PhD research there in 1983. A diet sample from a booby consists of dead fish that have yet to be digested, allowing us to weigh the sample, count the number of fish, and identify the species. Bonus: the bird that donates a diet sample will happily eat its fish back.

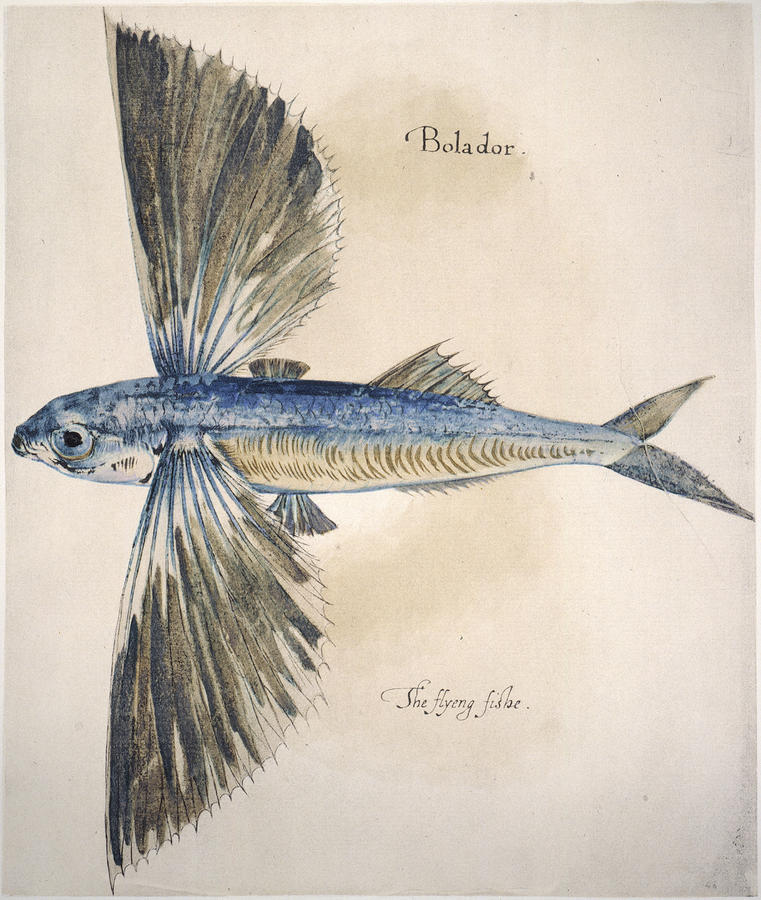

Before 1997, birds would return with large loads of one specific prey item, Pacific sardines, and regurgitate as soon as "you would pick them [the birds] up," because they were so full of food, Dave reports. But after the 1997 breeding season, he noticed that the birds returned with emptier stomachs, regurgitated less readily, and no longer returned with sardines. Sardines were replaced with flying fish that are less nutritious (like us substituting a bag of chips for a salad). What effect was this huge shift having on their survival and breeding? By studying the same individuals within the same population over time, he could observe it all happening.

Now sold in salt and vinegar

One of the biggest challenges to answering a question on survival and breeding is time. When the diet first shifted from sardines to flying fish, and the relative number of birds returning with full stomachs decreased, the researchers didn't have enough data yet to answer whether the change had a significant effect on an individual's survival or breeding success. So they collected more data and waited for more years to pass.

In the meantime, data collection occurred primarily in the field, including daily monitoring of Nazca booby nests where sleeping in a tent, bathing in the ocean, and getting pooped on daily by birds was the norm. The colony, where the Nazca boobies nest on the ground, was just a three-minute walk from our campsite near the beach. Each day on the island, I headed into the colony at the crack of dawn, armed with a field notebook, pencils, and my most important tool: a soft plastic "booby stick," kind of like a chew-toy for birds.

Whatever, human

Jenny Howard

A booby stick distracts a curious, nibbling bird while I read the unique five-digit number engraved into a metal band on the bird's leg, or gently lift a bird to see how many eggs it may be incubating. Trust me, it is best to avoid that bill chomping down on hands or fingers. Boobies bite. Hard.

In my notebook, I recorded the band number, the number of eggs in the nest, and the sex of the bird (males whistle, whereas a female will honk). Finished, I walk to the next nest and began the same process. Over the course of a season (one breeding year), we monitor daily more than 2,000 nests to collect information on the parents, egg lay date, hatch date, and if the chick survives. These data feed into a large long-term database on breeding behavior by Nazca boobies, providing details on which years an individual bird breeds and, if it does breed, whether or not it raises a chick successfully.

Floundering off flying fish

Emily M. Tompkins, PhD candidate, first author on the paper, and my lab colleague, emphasized that these long-term studies are incredibly "valuable because they give us time to understand how animals respond to environmental variation.” She used statistical models to calculate the effect of diet on Nazca booby reproductive success and survival. Her analyses incorporated thousands of uniquely banded birds, 1,345 systematic diet samples, and nearly 34,000 breeding records across multiple decades, an amazingly impressive data set in a natural population.

Kingdom of the boobies

Jenny Howard

The main finding: breeding success under the flying fish diet halved. After 1997, sardines weren’t present in the archipelago, and Nazca boobies were forced to forage primarily on flying fish. As a result, fewer chicks survived, meaning that fewer adults will be at the colony to breed in the future.

Nazca boobies are currently considered a "least concern" species with a stable population in the Galápagos Archipelago and on Malpelo Island, Colombia. But with climate change warming the oceans – the waters where Nazca boobies breed are predicted to warm about 8°F in the next 100 years – and sardines unable to live and breed in warmer waters, Nazcas will continue to rely on flying fish as their main food source and the population at our Punta Cevallos colony on Isla Española could decline in the future.

Further studies on the large Nazca booby population at Isla Malpelo could help us predict whether the species can survive sardines' absence at that oceanic island, where the waters are also predicted to warm and be unsuitable for sardines. Regardless of what may happen at Isla Malpelo, reducing the Nazca booby population to one oceanic island would be a significant change in conservation status for this species.

_(8202743477).jpg)

S̶a̶r̶d̶i̶n̶e̶s̶

This research has further ramifications for other Galápagos species that are dependent on the same food source as the Nazca boobies. The blue-footed booby, a sister species of the Nazca booby, is an iconic species for the Galápagos, attracting world-wide attention and support. An earlier study published by the same group in 2014 demonstrated that the blue-footed booby population in the Galápagos had declined by greater than 50 percent since the 1960s. This decline seemed connected to poor breeding that began in 1998 as a result of their primary prey, also sardines, disappearing throughout most of the Galápagos Archipelago.

As the recent Nazca booby paper points out, if sardines are not able to inhabit the Galápagos Archipelago with future warming oceans, the already declining blue-footed booby population may be in trouble in the long-term.

Ripples through the system

Galápagos sea lions, the playful animals that fascinate tourists to the Galápagos are adept hunters that eat a diversity of food items, but they prefer to eat sardines. Like the blue-footed and Nazca boobies, the sea lions, too, could be threatened with a declining population in the future because sardines may no longer be able to survive in the warming ocean off the Galápagos Archipelago. Galápagos sea lions are endemic to the archipelago; if their population blinks out, that predator will be gone because no oceanic island is close enough (and further north) for relocation to cooler waters.

Island boss

While we are familiar with polar bears disappearing with melting sea ice, the Nazca booby is a critical reminder that tropical marine species may also be negatively affected by climate change. The loss of sardines from the diet of Nazca boobies, blue-footed boobies, and Galápagos sea lions could have large implications for other species farther down the food chain. Additionally, Galapagos tourism is driven by the desire and ability to see these beautiful species; climate change reducing their populations could have downstream effects on the tourism industry so vital to the country of Ecuador. As in long-term research, only time will tell.

I am wondering how long Nazca boobies have lived in the Galapagos, and whether there have been any studies over even longer timescales (such as thousands of years… but not at daily resolution, of course!) about their population, because it seems like the 1997 El Niño event had a major impact on their diet.

Over the past couple thousands of years, El Niño events have changed in frequency and strength, and (presumably) the boobies were able to persist through those events. It would be really interesting to see how they changed their diet during periods with a lot of El Niño events.