MDMA can help fight PTSD — if scientists are allowed to use it

How psychedelics could remain illegal, even if research shows they help heal

It's normal for victims of trauma to experience feelings like stress, grief, anger and guilt. Most people recover after a few months. But for some people, the anxiety never subsides, and they start to experience intense flashbacks. We call this post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and over 9 percent of Americans will suffer from it during their lifetimes. It's even more common among those who have experienced war, both as soldiers and as civilians in conflict zones, and it can be a major obstacle for refugees as they try to integrate into a new society.

According to the U.S. Department of Defense, as many as one in six Marine veterans of the Iraq War developed symptoms of major depression and post-traumatic stress disorder.

Image by The Marines via Flickr

The disease is notoriously hard to treat. But recently, scientists have started testing out a new, promising, and controversial tool: psychedelic drugs.

PTSD is usually treated with a combination of counseling and medication. Clinicians have a patient recall situations that produce anxiety and then help them reframe the event or develop strategies to regulate their emotions. But there's a common problem that can make talk therapy difficult: when PTSD patients recall traumatic events, they can have violent flashbacks, causing them to shut down from stress, which makes therapy impossible.

To make the flashbacks easier to tolerate, clinicians often administer drugs like Prozac or Zoloft to accompany therapy. But that doesn't work for an estimated 33 percent of patients. That's why some clinicians have become interested in using the psychedelic drug MDMA.

Early results from a team lead by Michael Mithoefer at the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic studies have been promising. Their treatment begins with talk-therapy sessions to prepare the patient for the experience. Then, the patient is given 50–125mg of MDMA under the supervision of a psychiatrist and has an hours-long psychedelic experience during which the clinician guides them through anxiety-provoking scenarios the same way they would during regular talk-therapy.

PTSD victims often experience flashbacks to traumatic events.

Photo by Peter Murphy via Flickr

The MDMA suppresses the panic response and increases feelings of trust in the therapist to create a 'therapeutic opening' during which the patient can recall their trauma in a state of relaxation. By recalling and reframing these events several times, the patient's acute stress response to their traumatic memories eventually diminishes. According to their most recent data, over 80 percent of patients who undergo this therapy are free of PTSD after one year.

Naturally, there are still some open questions about this treatment, like how to identify good candidates for it. That's why the research team is proceeding with clinical trials with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), designed to test the efficacy of treatments in successively larger groups of patients. There are four FDA trial phases, and the treatment is currently in Phase III, which will evaluate the process with several hundred patients over several years.

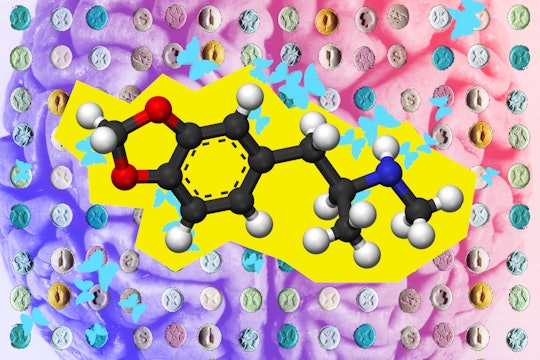

A visualization of an MDMA molecule.

But even if the treatment makes it through all four phases, there is a major obstacle to the adoption of this treatment: MDMA is illegal. It's classified as a schedule I drug, meaning both that possessing it is a crime and that it is considered a substance that has no accepted medical use. To study it, researchers have to receive a special permit from the DEA and order samples from an authorized chemical company.

The investigators researching MDMA's use in treating PTSD will presumably request that the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), which regulates drug scheduling, move it to schedule II. Schedule II drugs include amphetamines, barbiturates, and most pure opioids, and still have severe restrictions on their prescription and therapeutic use. They can only be used under strict medical supervision, and there are restrictions on the prescriber and the number of doses that can be prescribed, among other things.

But there's no guarantee that if MDMA qualifies for FDA approval that the DEA will reschedule it accordingly. The DEA often considers factors outside of the science in their assessment, which has caused a fair amount of of historical tension between narcotics laws and the medical establishment. That tension has recently bubbled up to become a key part of the modern political debate thanks to opioids. In the early 2000s, for example, the DEA moved several opioid-based drugs from schedule III to schedule II, despite the FDA concluding the move wasn't necessary.

It would be a setback if this treatment won FDA approval but could not get reclassified, but that is a risk of working with schedule I psychedelics. At minimum, the research may still yield important insights into how PTSD works, and how drugs like MDMA make treatment easier. By learning more about the systems, cells, and molecules that drive PTSD, researchers of the future might be able to tailor new therapeutic tools. It may be possible, for instance, to reengineer the molecule to separate the psychedelic and therapeutic activities of MDMA in a way that reduces the potential for abuse and diversion.

Alternatively, Mithoefer's success might inspire new ways of thinking about PTSD that open other creative new approaches for patients who don't respond to traditional treatments.