Matteo Farinella

Meet Maria Sibylla Merian, the naturalist who painted insects in living color

One of the first to recognize insect metamorphosis, she's finally getting her dues after 300 years of obscurity

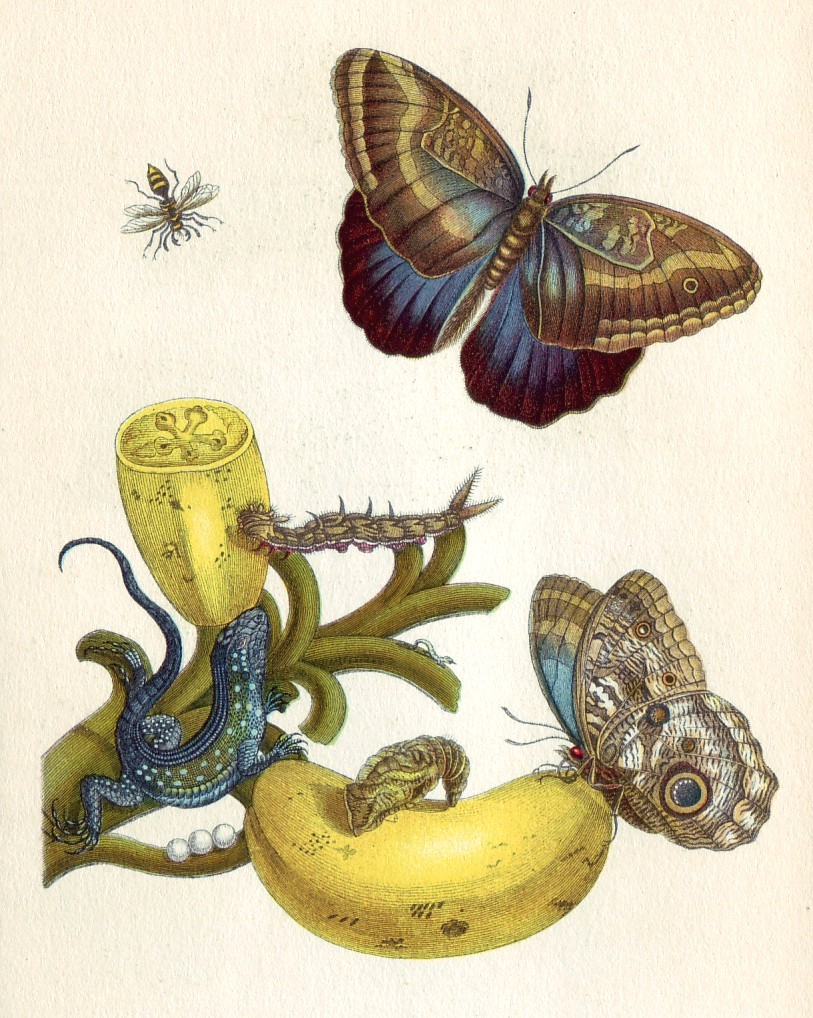

Maria Sibylla Merian was a leader in natural science, an ecologist and an entomologist before those terms existed. Merian looked at the world differently from other naturalists. While men such as Carl Linnaeus worked hard to classify and categorize isolated dead specimens of animals and insects, Merian chose to study them as living creatures. As a result, she witnessed behaviors, changes, and interactions that others could never have seen.

Matteo Farinella

Merian was born in Frankfurt in 1647. Her father died when she was three years old, and her mother married Jacob Marrel, a painter who encouraged Maria to develop her artistic skills and her passion for collecting bugs. Marrel left the family when Merian was 12, and from then she worked to support herself and her mother. She collected insects to paint, and would often stay up late and paint by candlelight to be sure of catching the moment when a chrysalis opened.

After separating from an unhappy marriage, Merian became an unusual figure in 17th century Dutch society. She was a self-supporting female scientist in a time when women were largely homemakers and barred from institutes of higher learning. After moving to Amsterdam in 1691, she taught painting to fund her expeditions.

One of the boldest choices Merian made was to undertake a perilous expedition to the Dutch colony of Suriname. When she arrived there in 1699 with her youngest daughter, Merian was frustrated by the total lack of natural curiosity of the colonists, and their unwillingness to assist her. So Merian turned for help to the enslaved Africans and Indigenous people of Suriname who worked on the Dutch plantations

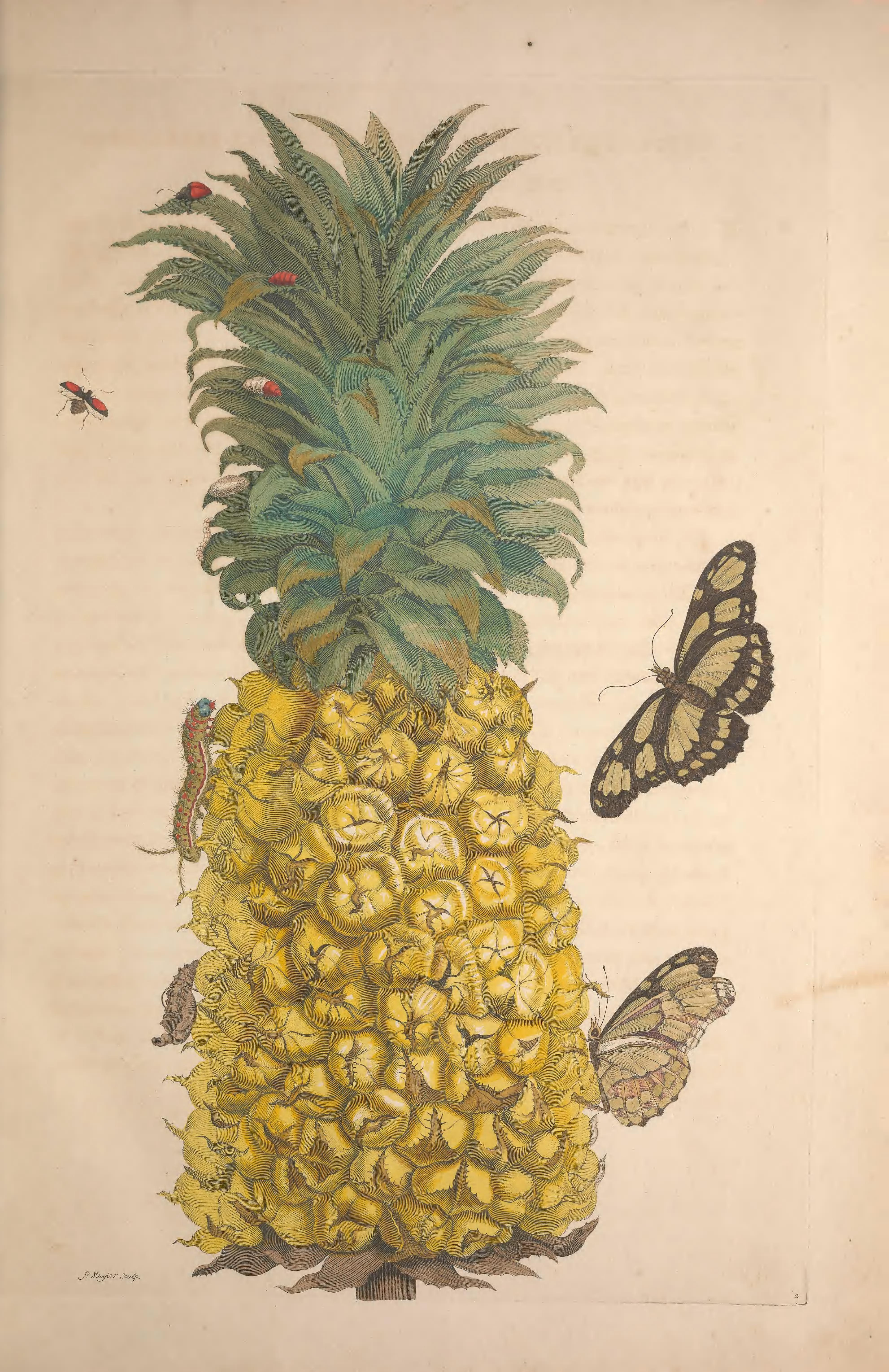

Butterflies from Merian's book, Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium

While Merian lamented some of the harsh treatment of slaves on the plantations, she was certainly no abolitionist herself. She stayed in the territory of the Dutch West India Company, which had become rich by trading people. Merian kept slaves of her own in Suriname, and in so doing, she supported and participated in the colonial practices of her time. Because of this, we have to doubt how willingly assistance was given to her research efforts.

We do know that African and Indigenous slaves were instrumental in Merian’s work in Suriname, bringing her samples she might never have reached, and teaching her how to use certain plants. In one story, enslaved Indigenous women showed Maria how some particular seeds were used to terminate pregnancies and spare their own children from enslavement. Merian recorded and used native names for many of the plants mentioned in her book Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium.

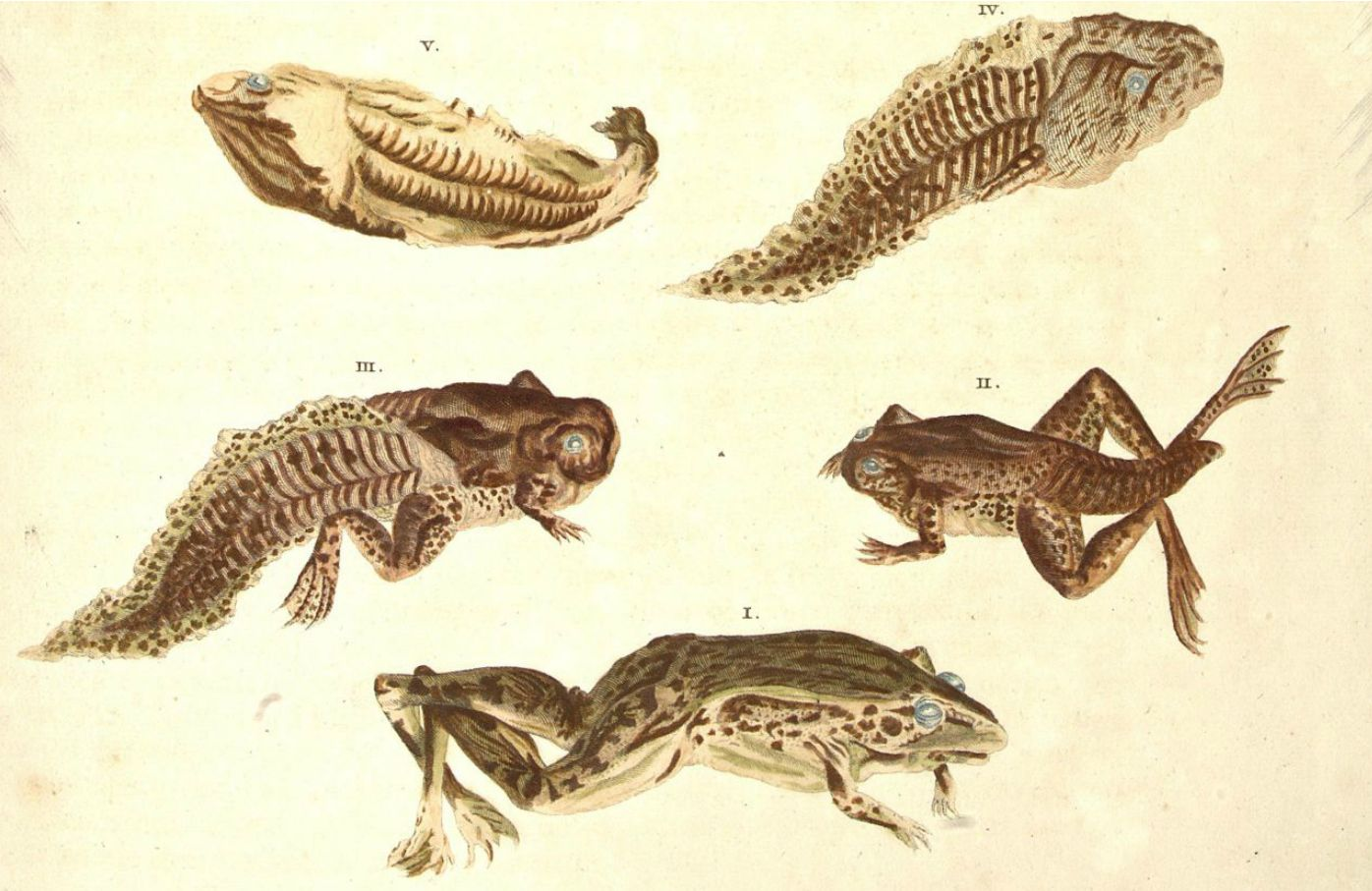

Frog life cycle from Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium

Metamorphosis was a cornerstone of Merian’s theories of insect life, and was a major way she diverted from common wisdom of the time period. In her 1679 Der Raupen wunderbare Verwandlung und sonderbare Blumennahrung (The Caterpillars' Marvelous Transformation and Strange Floral Food), she depicted the complex life cycles of moths and butterflies. This directly refuted the generally accepted truth of “spontaneous germination" — the ancient theory that life can come from non-life, such as the idea that insects erupt spontaneously from decaying matter or dust, frogs are birthed from raindrops, and wheat left in a dark corner will produce mice.

Merian’s work was referenced heavily in Linnaeus’s Systema Naturae (1735), which presented the first systematic classification of species. She received praise from Goethe for her ability to blend art and science. And Erasmus Darwin, grandfather of Charles, cited her in his influential work The Botanic Garden. Indeed, she was well regarded by many of her educated contemporaries and received a sponsorship from the City of Amsterdam to support her Suriname expedition.

So why is her name completely absent from the subsequent 300 years of ecology? In The History of Creation (1866), Ernst Haeckel called Merian “the forgotten mother of animal developmental biology and ecology.” As recently as 1982, she was completely omitted from Ernst Mayr's Growth of Biological Thought which recounted 2000 years of biological study. Merian’s work was always published under her own name, so there was no chance of her discoveries being mis-attributed to other people. So how was she lost?

%2C_74_plate_18_-_BL.jpg)

Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium. Notice the bird-eating spider in the bottom of the image.

Public domain.

Despite the respect and admiration of her peers, Merian’s work did not enrich her family, and she was buried in a pauper’s grave after having to sell many paintings and specimens. In the years after her death, changes were made to her illustrations. The scenes she had depicted accurately, based on meticulous observation, were altered to incorporate imaginary insects and re-colored to be more aesthetically pleasing.

To some, the obvious errors and fictions in subsequent printings of her work were similar to other stories she told – such as a tarantula that can eat a bird, or the notion that ants can build bridges with their bodies, animal habits that we now know to be common in the tropical areas Merian visited.

Illustration of butterflies and a pineapple from Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium

The naturalist Lansdown Guilding took it upon himself to write a scathing critique of Merian and her work, particularly her Suriname illustrations. 100 years after her death, he published Observations of the Work of Maria Sibylla Merian on the Insects of Surinam. Guilding himself had never travelled to Suriname, yet he felt confident enough to publish this text that ridiculed Merian for “careless”, “vile and useless” inaccuracies that “every boy entomologist” could spot.

Of course, his critique was based on the versions of Merian’s books that were altered after her death. And yet the sexist tone of his criticism is impossible to miss. Guilding's point is further undermined by his dismissal of all observations that resulted from collaboration with African slaves and Indigenous people, whom he considered to be innately unreliable.

With her reputation in tatters, Maria came to be viewed as a silly old lady who made pretty pictures, which continued to be admired in the art world, but were no longer considered scientific.

Lizards and butterflies from Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium

The record began to be rectified 300 years after her lifetime. In 1993, Sharon Valiant wrote Maria Sibylla Merian: Recovering an Eighteenth-Century Legend. In this piece, Valiant reviews some recent publications of Merian’s work, which included collections held in the Soviet Union, and the first ever English language publication of the re-titled Maria Sibylla Merian in Surinam.

While men like Guilding fade into obscurity, Merian's rehabilitation continues. Her original illustrations are now displayed in art and science museums around the world. As she drove her own career and education, she is considered by some to be a leader of womens' rights. She has been featured on a Google Doodle, a German stamp and bank note, and is the subject of several biographies. Multiple new species discovered since her death have been named after her – including her bird-eating spider, Avicularia merianae.