These unregulated, potentially dangerous chemicals are probably already in your bloodstream

Researchers have known that there are unsafe compounds in our water for decades, but the government is just starting to catch up

On October 4, 2018, an Ohio firefighter and a former corporate defense attorney filed a class-action lawsuit representing every American citizen with a certain class of chemicals in their blood — about 98% of the US population, all in all.

The chemicals used as criteria in the suit are called PFASs (pronounced "pee-fass"), and are unregulated at the federal level. PFASs are found in the blood of almost all American adults, making a class of chemicals perhaps one of the most unifying American characteristics of our time.

The suit is seeking to make companies that produce PFASs pay for studies that would rigorously track the health effects of the chemicals. We don't have a very clear picture regarding how PFASs impact human health or how the compounds behave in the environment.

What we do know is bad. Some PFASs are associated with cancer, developmental effects, liver problems, and immune system impairment in humans and other species. PFASs are currently wreaking havoc in highly exposed communities across the country, with more uncertain but concerning effects related to low-level chronic exposures across the general population.

PFASs producers started to realize these risks well before they shared this information to the public, and cooperated with the EPA to phase out the most toxic types of PFAS, called PFOA and PFOS, in the 2000s. PFOS is also restricted by an international agreement, the Stockholm Convention. Other versions of PFASs are still being produced and introduced into the environment at high levels, with uncertain consequences for living creatures.

I grew up in two areas with high PFASs concentrations documented in water. I had no idea they were there until I started pursuing a PhD in environmental chemistry.

Even with this degree, it can be difficult to determine PFAS exposure, though they are literally all around and inside us. How many other Americans unknowingly drink or swim in contaminated water, like I did? According to recent research and modeling, drinking water with unsafe PFASs levels has likely reached millions.

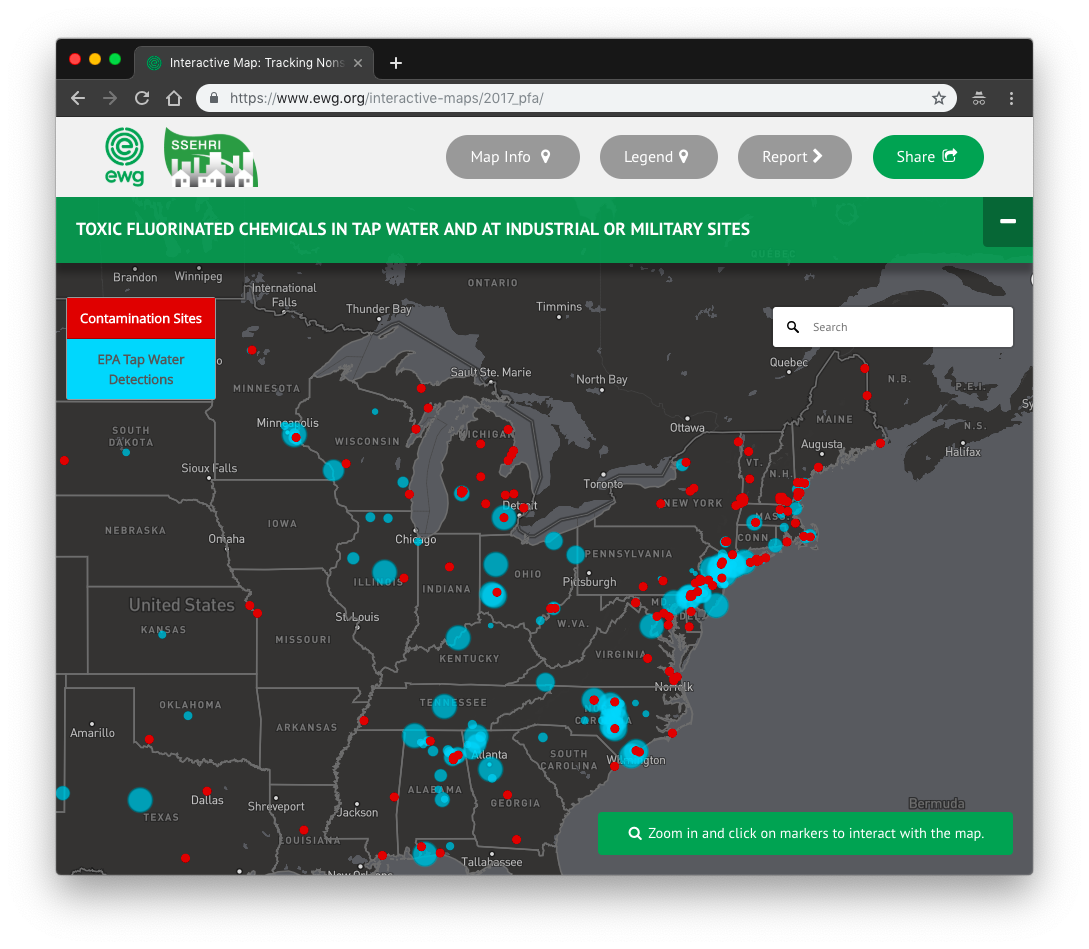

The Environmental Working Group and Northeastern University's Social Science Environmental Health Research Institute maintain a map of PFAS contamination sites and detections across the country

EWG and SSEHRI

PFAS 101

These pollutants were invented in a burst of ingenious yet short-sighted organic chemistry in the 1940s, and have since come to be known as poly- and perfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS or PFASs, previously PFCs or perfluorocarbons).

A PFAS molecule consists of a chain of carbons with fluorine atoms attached, with some additional specialized atom group thrown in for flavor, called functional groups. There are many iterations of this structure, but they all fall under the PFASs family umbrella because they heavily rely on the carbon-fluorine (C-F) bond.

The C-F bond is one of the strongest bonds in chemistry, and it renders powerless an arsenal of chemical and environmental mechanisms that degrade other pollutants. The basic PFAS structure is so stable that many degradable versions of PFASs, with fewer C-F bonds, get together in the environment to re-form structures with more C-F bonds, making them more stable — and much more toxic. It's like the chemical equivalent of Gremlins, as "friendly" molecules turn ugly under the right conditions.

This characteristic structure also makes PFASs two-faced: The carbon chain doesn’t like to associate with water, but various functional groups are quite chummy with it. This means that PFASs are both water and oil repellant, an extremely valuable quality that has made them extremely popular in consumer, industrial, and military applications.

As a result, PFASs are everywhere: fire-fighting foams, nonstick cookware like Teflon, stain-resistant carpet, water-resistant clothing, food packaging, compostable plates, some cosmetics, and other consumer products that repel oil, grease, or water. They've also made their way into air, rain, household dust, glacier ice, the depths of the ocean, wildlife, surface water, and drinking water.

Humans have not escaped PFASs, as the lawsuit duly notes. PFASs in humans primarily come from food and drinking water. Military personnel and industry workers are more exposed through occupational exposures, associated with military bases and production facilities.

Even worse, children have higher PFAS burdens compared to most adults, because they put lots of PFAS-containing stuff in their mouths, spend more time playing on stain-resistant flooring, and receive a starter dose of PFASs from their moms before birth and during breastfeeding.

A PFAS turning point?

The recent class action-suit comes at a critical moment, as improved analytical techniques are identifying more contaminated sites around the country while health researchers continue to set acceptable levels of exposure lower and lower.

In June, the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR), an arm of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) issued an updated draft toxicological profile for PFASs. A White House aide reportedly described the document as a “public relations nightmare," as it suggests "safe" levels of PFASs are about 10 times lower than the current EPA drinking water guidelines.

Firefighting foam

U.S. Pacific Fleet / Flickr

The ATSDR report provides minimum risk levels, or concentrations that will likely not translate to appreciable health effects. The new levels are based on health studies that say that PFASs affect the immune system and development at much lower levels than previously thought, particularly for children and other vulnerable people.

For drinking water, this means acceptable concentrations are around 7 parts per trillion of PFOS and 11 parts per trillion for PFOA, according to Laurel Schaider, a research scientist at the Silent Spring Institute. Right now, the EPA’s 2016 guidelines set an acceptable drinking water concentration for PFOA and PFOS at 70 parts per trillion, about ten times higher than the draft report's thresholds.

But just how tiny is a part per trillion you ask? One part per trillion is about one drop of water in an Olympic swimming pool; by the standards in the ATSDR report, a PFASs exposure greater than approximately two thousandth (0.002) of a drop in the average yearly water intake of an American adult could be considered potentially unsafe.

Trying to visualize 0.002 of a drop illustrates what sets apart PFASs from the slew of other chemicals in our environment: they are harmful at really low levels, yet millions of people are subjected to them via drinking water and other sources every day.

PFASs on Capitol Hill

The ubiquity of contamination and mountain of uncertainties regarding PFASs effects have spurred legislation in addition to litigation. The PFAS Accountability Act of 2018 and the PFAS Federal Facility Accountability Act of 2018 were introduced to Congress in August and September of 2018. The bills seek to increase and coordinate federal and state level responses to PFASs contamination across the country, and have so far received bipartisan support.

These resources provide more information and resources if you're concerned about PFAS contamination in your community:

- STEEP: NIEHS/Superfund Research Program

- Silent Spring Institute

- ATSDR: PFAS and your health

- The C8 Project

- The PFAS Project

- EPA web resources

The PFASs saga will continue to play out in Congress and the courts, yet ultimately consumers hold more direct power than many may realize. As public awareness grows surrounding these compounds, some companies are working to remove PFASs from their products. Consumers can continue to demand and seek out PFASs-free products to help remove these chemicals, still understudied and potentially dangerous, from the consumer arena.

This was a great article introducing me to a class of chemicals I had never heard of before! With microplastics being found in human feces and now this stealthy chemical hiding out in our blood – it is the “new” reality of how our human decisions come back to attack us. Pretty terrifying. How do PFA levels in human blood compare to levels found in wildlife? If these chemicals are in water bodies, I assume aquatic/marine organisms might be the most affected – are there any studies yet comparing PFA levels of aquatic organisms at different levels of the food chain?