"Skeleton Keys" reveals the secrets hidden inside your bones

Brian Switek's book breathes new life into our understanding of old bones

What will happen to your bones after you die? Will they be venerated as relics? Buried with care by your loved ones? Preserved as part of a museum's collection? Each of these treatments says something different about the value - religious, cultural, or scientific - that we place on the human skeleton. From Neanderthals burying their dead in prehistoric times to the University of Tennessee's "Body Farm" where forensic anthropologists study the processes of decomposition, the skeleton has been deeply significant to different groups of people for millennia, and every skeleton has stories to tell about who a person was and how they lived.

Science writer Brian Switek's new book, Skeleton Keys (out March 5), aims to tell these stories, taking readers on a fascinating tour of the human skeleton, from its humble evolutionary beginnings as the hard parts that protected fossil fish from predators, through its use in reconstructing the lives of past people and populations, to questions of what happens to our skeletons after death (both culturally and with an eye toward Switek's own potential for future fossilization). The narrative in Skeleton Keys spans millions of years and offers readers insights into their own anatomy and evolution, but is also very current in its treatment of how the skeleton has been misused to prop up problematic assumptions about sex, gender, and race.

The author's fascination with bone comes out of his background in paleontology, the subject matter he covered in previous books like My Beloved Brontosaurus. As he says in Skeleton Keys, he'd mostly avoided the human skeleton in the past, preferring to explore the more majestic and mysterious remains of the dinosaurs. But he was driven to consider his own osteological architecture out of a need to "know thyself."

Powerhouse Museum via Flickr

His take on human osteology in Skeleton Keys is a holistic one, drawing on many different perspectives (scientific, cultural, ethical). Switek uses this book as a way to illustrate the diverse roles skeletons play in human history, science, and society. One of his best examples of this comprehensive view comes from the surprising discovery of the skeleton of British King Richard III, last seen in 1485 until he was excavated from beneath a Leicester parking lot in 2012. To some, he's the murderous villain of the eponymous Shakespeare play, the hunchbacked king who had his two young nephews imprisoned and murdered in the Tower of London, but others (like his fan club members, the Ricardians) maintain his innocence. While the scientists that analyzed his bones were unable to exonerate him, his skeleton told them where he grew up, what he ate as an adult, and how he met his brutal end on the battlefield. His story shows how the skeleton can be both personally meaningful and scientifically informative.

I'd argue that the different perspectives Switek brings to the book all boil down to ways that people have tried to "know thyself." Our skeletons are shaped by our evolutionary history, they are modified in life by how we use them and what happens to us, and they've been used to both unify and divide groups of people.

And Switek gets into all of these areas in Skeleton Keys. For him, it's not just that bones are interesting from a scientific context (though he does dig into their paleontological past and explains basic skeletal biology with more flair than I've ever brought to that particular lecture), it's that they bring with them a lot of cultural baggage, as well. For example, he delves into the racist history of their study - anatomical arguments that were once used to bolster slavery, segregation, and the dispossession of Native Americans, among other things, which are now rearing their ugly heads again thanks to the rise of personal genetic testing and ancient DNA. He doesn't shy away from a lot of the contemporary issues in the study of human bones, devoting time and care to the question of who should be the keepers of the dead.

Switek covers an incredible amount of ground, some of it potentially familiar to readers (like the 20-year Kennewick Man/Ancient One legal battle between a group of anthropologists and the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation over the skeleton of an approximately 8,500 year old Native American ancestor found in Washington) and some of it new even to osteological professionals like me (like the fact that people can develop pathological penis bones in response to physical trauma). He tells a compelling story, though his writing leans a tad poetic for my taste, as someone for whom the osteology lab has become less a place of awe and more an ongoing project in proper curation.

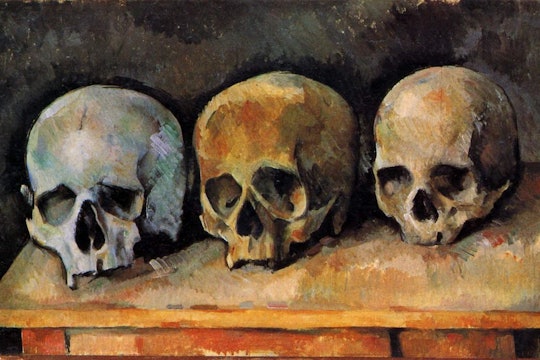

One of the most interesting moments of the book for me was his discussion of the "Red Market" for human remains. I had no idea selling skeletons was still such big business or that I'd only have to hop onto Instagram to find skull vendors. Hopefully by the time you get to this point in Skeleton Keys you'll have gained a new appreciation for your skeleton and won't feel motivated to purchase anyone else's as macabre decor.