Christina Morillo on Wikimedia Commons.

Your language brain matters more for learning programming than your math brain

New research contradicts long held assumptions about coding

When you think of learning another language, you probably think of French, Spanish, or Chinese. But what about Python or Java? The two processes might be more similar than you'd think.

A recent study published from researchers at the University of Washington showed that language ability and problem solving skills best predict how quickly people learn Python, a popular programming language. Their research, published in Scientific Reports, used behavioral tests and measures of brain activity to see how they correlated with how fast and well participants learned programming.

For the study, 42 participants were recruited to try a popular online coding course through Codeacademy. They were asked to complete ten 45-minute lessons of the "Learn Python" course. From the 36 participants who completed the study, they were able to determine rate of learning and how well the students learned the lessons.

Before doing online classes, participants did a battery of tests designed to look at math skills, working memory, problem solving, and second language learning ability. During their online programming course, the researchers were able to track how quickly they learned and how well they did in the quizzes built into the online software. They also completed a quiz and coding task at the end of the study to look at their overall coding knowledge.

The researchers where then able to compare the test results from before and after the Python course. The goal was to determine how much of the differences in participant Python learning could be explained by their performance on the different pre-tests: how much did memory, problem solving, and an aptitude for numbers or languages influence how quickly they learned to code?

The participants learned Python at different rates, and had different programming abilities at the end of the study. The researchers looked at the relationship between the skills covered in the pre-test skills and the variability in how participants learned Python. They found that how well students learned Python was mostly explained by general cognitive abilities (problem solving and working memory), while how quickly they learned was explained by both general cognitive skills and language aptitude.

Language aptitude explained almost 20% of the difference in how quickly people learned Python. In contrast, performance on the math pre-test only explained 2% of the variability in how quickly students learned, and didn't correlate at all with how well they learned. Learning to code depended much more on language skills than it did on numerical skills.

Python really is another language.

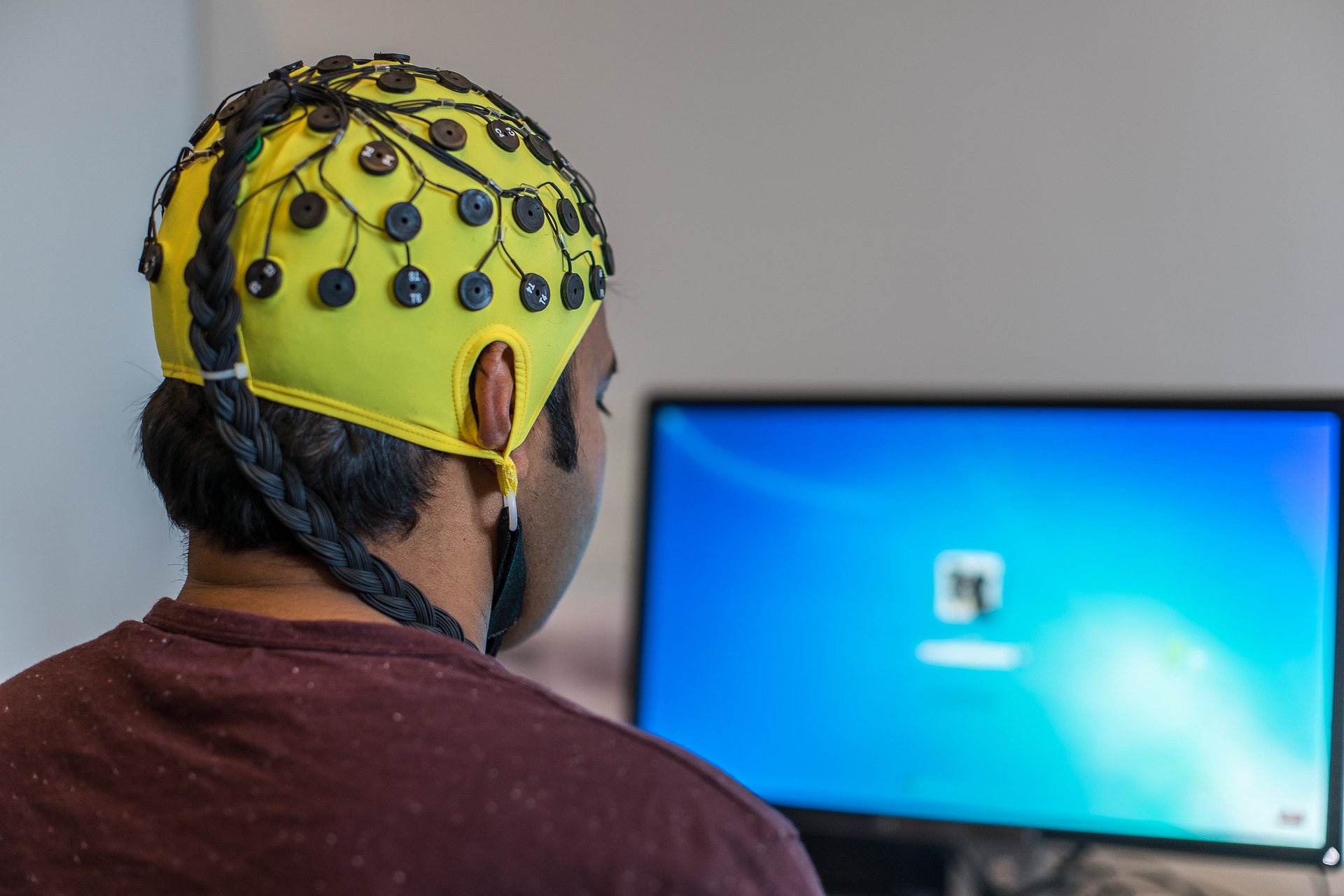

Additional evidence for the importance of language skills came from electroencephalography (EEG) data. EEG is a method of measuring brain activity through electrical patterns that can be recorded through the skull. Prior to their online learning tasks, participants were given a resting state EEG, which measures patterns in the brain when the subjects were relaxed and doing nothing.

Electrical activity at rest has different patterns. One of these patterns is slow waves of electrical activity called beta oscillations. Past research has shown that high levels of beta oscillations at rest are linked with the ability to learn a second language.

ulrcichw on Pixabay

In this study, high levels of these beta oscillations were associated with faster learning and more programming knowledge. While this finding gives additional support to the connection between language learning and learning to code, it's not clear (yet) how beta oscillations are related to learning outcomes, and more research is needed.

Taken together, these result make the case for language skills being an integral aspect of learning programming (or at least of learning Python), while math skills weren't very predictive of how well or quickly participants learned. This idea has important implications for the perceptions surrounding programming, which is often viewed as a "math intensive" field.

There are many assumptions about programmers, especially about who makes a good programmer. Women often feel they don't fit with the idea of a "typical" computer programmer. However, girls typically have higher language skills than boys on average. Since language abilities were shown to predict ability to learn programming, perhaps women should have more of a reputation for being "good" at programming.

It's true that some fields require both math and programming skills, but those aren't necessarily the majority of programming jobs available. Based on this study, the requirements for advanced math classes for every computer science major seem unnecessary, and increased flexibility over math requirements could help recruit and retain students.

Explicitly connecting language skills to programming and providing education options that don't require advanced math may help improve diversity, while still teaching students the programming skills they need. Indeed, "bootcamp" style options that are rapidly growing in popularity lead to programming careers without forcing calculus on their participants.

As programming becomes a pre-requisite for many jobs, it's time to question long held assumptions about pre-requisites for learning programming. Based on the results from this new study, universities and individuals should rethink how they characterize learning programming and what abilities play a role. There's a lot of people out there who "aren't math people," but they just might be computer science people.

This is an excellent piece on really important research. Programming is becoming a valuable skill on the job market, but there is still this idea that you have to be good at math in order to learn it. And this creates inequality. For example, previous research has shown that girls have less math confidence, which means they might also underestimate their programming abilities.

I also wonder what this research might mean for how we teach programming. I was taught with nearly exclusively math-oriented exercises, like calculating a fibonnaci number or implementing a sorting algorithm. Maybe when teaching programming, we should start using more creative and language-oriented exercises, which could help a larger number of students learn how to program.

Overall, I’m glad we’re starting to dispel the idea that programming is only for math geniuses. I love the final line, which is so true: “There’s a lot of people out there who “aren’t math people,” but they just might be computer science people.”