Here's how to avoid outliving your own bones

Hit the gym and find the sunshine vitamin

To reach the average lifespan of 80 years, aging is unavoidable. Unfortunately, that means osteoporosis is too – the loss of bone density affects millions of people above age 70. Sufferers spend decades with the progressive disease, living with the increasing risk of fractures and becoming more dependent on others over time. Eventually, many people with osteoporosis can't even use the bathroom without assistance.

People from previous generations generally only lived into their sixties; bone health was never something they needed to worry about. They maintained their weight, cooked more meals, and had fewer technology distractions. Our generation has an increasing rate of diabetes, fast food restaurants on every corner, and technology so advanced we can't even keep up with the newest iPhone on the market. Our bones are taking on more of a load for a longer period of time; we're outliving our bones and doing absolutely nothing to counteract it.

We can't stop aging, and there are no cures for osteoporosis, so what can we do to help prevent this disease?

The wrong bone diet

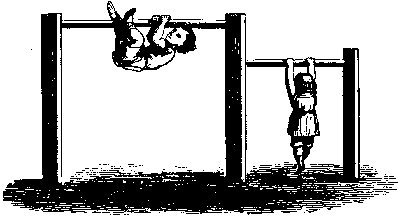

According to a British study from 2015, the key is to make sure to plan for old age by building bone density in your younger years. We achieve peak bone mass during our twenties and thirties. The amount of bone mass each person has is modifiable in this time period depending on exercise and diet. We can't change the fact that we are aging – that's life – but we can change our diets and exercise regimen. Weight-bearing exercise in young adulthood leads to stronger, bigger bones.

After age 30, bone levels begin to plateau, or maintain their strength, but they cannot become any stronger. Once we reach 50, our bone health significantly begins to decline, and at a fast rate. By building up as much bone as we can by 30, we can put off osteoporosis for five, or 10, or 15 years.

Here's how: bone is a highly dynamic organ and is constantly renewing itself. Bone maintains its structure through a balanced ratio of both osteoblasts – cells that form bone – and osteoclasts, cells that eat away at the bone. Physical exercise helps maintain an even ratio between osteoblasts and osteoclasts, meaning for every part of bone that is 'eaten away,' new bone is formed, ultimately maintaining a healthy balance.

Diet, muscles, foresight

Muscle also plays a role in bone health, because physical exercise stimulates muscle contraction, leading to increased muscle function and bone formation. As we age, our muscle function declines, as does our mobility. Our bone strength declines accordingly, and the osteoclasts start to outnumber the osteoblasts, leading to an uneven ratio of bone formation and bone being eaten away, causing a reduction in bone mineral density and strength.

Start young

Dietary factors, like taking sufficient calcium and vitamin D, also play a role in developing and maintaining our bone strength. Vitamin D is essential in order for your body to properly absorb calcium; without these, our bones will not be able to maintain their strength. If you are not willing to eat foods rich in either calcium or vitamin D, you can easily get the daily recommended calcium and vitamin D levels as a pill, making this a very accessible preventative measure.

It can be hard for younger adults to think ahead about how what they do now will impact them decades later. But chronological and biological age aren't the same thing. A 25 year old who doesn't exercise and does smoke is increasing his biological age – and quickly. So even though the average lifespan is well into the eighties, you're actually hitting the biological "80" when you're only chronologically 60, in extreme cases. We need to care about our bones so that we don't outlive them.

As a neuroscientist that is deeply interested in the how bone and the brain talk to each other, a general understanding of bone health goes a long way. Menopause, a process that links both the bone and brain, accelerates osteoporosis rapidly, and speaks to the interventions and preventative measures that are so important and brought forth here.