Greta Moran

While Congress does nothing, New York City passed its own climate legislation

With the Green New Deal stalled, cities are stepping up with their own

Under a bleak gray sky last Thursday, Maritza Silva-Farrell, the executive director of ALIGN, mounted a podium in front of New York City Hall. She reminded an enthusiastic crowd of labor, environmental, and community organizers of what brought them together —the devastating impact climate change has already had on the city. “We’re talking about 400,000 New Yorkers,” she said, referring to the those living in the city’s floodplains during Hurricane Sandy in 2012. “Their lives changed forever.”

A couple hours later, New York City passed groundbreaking climate legislation, including the largest mandated pollution reduction in any city in the world, just ahead of Earth Day. “Future generations will look back at this moment and they will think of this as one of the most important bills,” Bill Lipton, the director of the Working Families Party, told the crowd at City Hall. “We are starting to turn a corner.”

The New York Climate Mobilization Act is actually a suite of 10 bills, most notably the landmark 'Dirty Buildings' law. The bill, introduced by New York Councilman Costa Constantinides, mandates that New York’s tallest buildings — those over 25,000 feet — will need to slash their emissions through energy-efficient building upgrades. This targets New York City’s surprising worst polluter — skyscrapers — while also creating thousands of jobs in design, renovation, and construction.

Remarkably, buildings are responsible for a staggering 70 percent of the city’s total greenhouse gas emissions, and the tallest ones are particularly noxious. Out of New York City’s 1.1 million buildings, 50,000 are responsible for 30 percent of the city’s emissions. “When you hear that number, it blows your mind,” said Constantinides. The new Act requires the tallest buildings to cut their emissions 40 percent by 2030, and over 80 percent before 2050.

Zazie Beetz, actor and climate activist, speaking outside of New York City Hall.

Greta Moran

The ground-breaking bundle of legislation is being hailed as a Green New Deal for New York City — and rightly so. The Act is one of the first “to comprehensively set standards to cut pollution at the pace and speed of the climate crisis,” Pete Sikora, an organizer with New York Communities for Change, told Massive Science.

Not only does the bill have global consequences, it will also have local impacts. Fewer emissions will likely lower the number of asthma cases in emergency rooms. And, along with the promise of rapid decarbonization, the bill honors another tenet of the Green New Deal: the expansion of good, blue-collar jobs. As New York puts in place more stringent policies, these kinds of jobs will continue to increase in order to handle the retrofitting”. “Many of these jobs will be good, union jobs,” Sikora explained, as unions comprise a strong force in the city’s large building renovation industry.

But it’s been a long road to get to this point. Though billed as part of a national conversation on emissions, the idea far predates Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s push for climate legislation. As far back as 2009, then-Mayor Bloomberg called for legislative changes that would have required energy efficient upgrades in large buildings — but he met with intense opposition from powerful building owners and the real estate industry.

“There's nothing new about a Green New Deal. We've called it “climate justice” for decades,” said Eddie Bautista, the executive director of the NYC Environmental Justice Alliance, in his speech at the rally. “We call it a ‘just transition.”

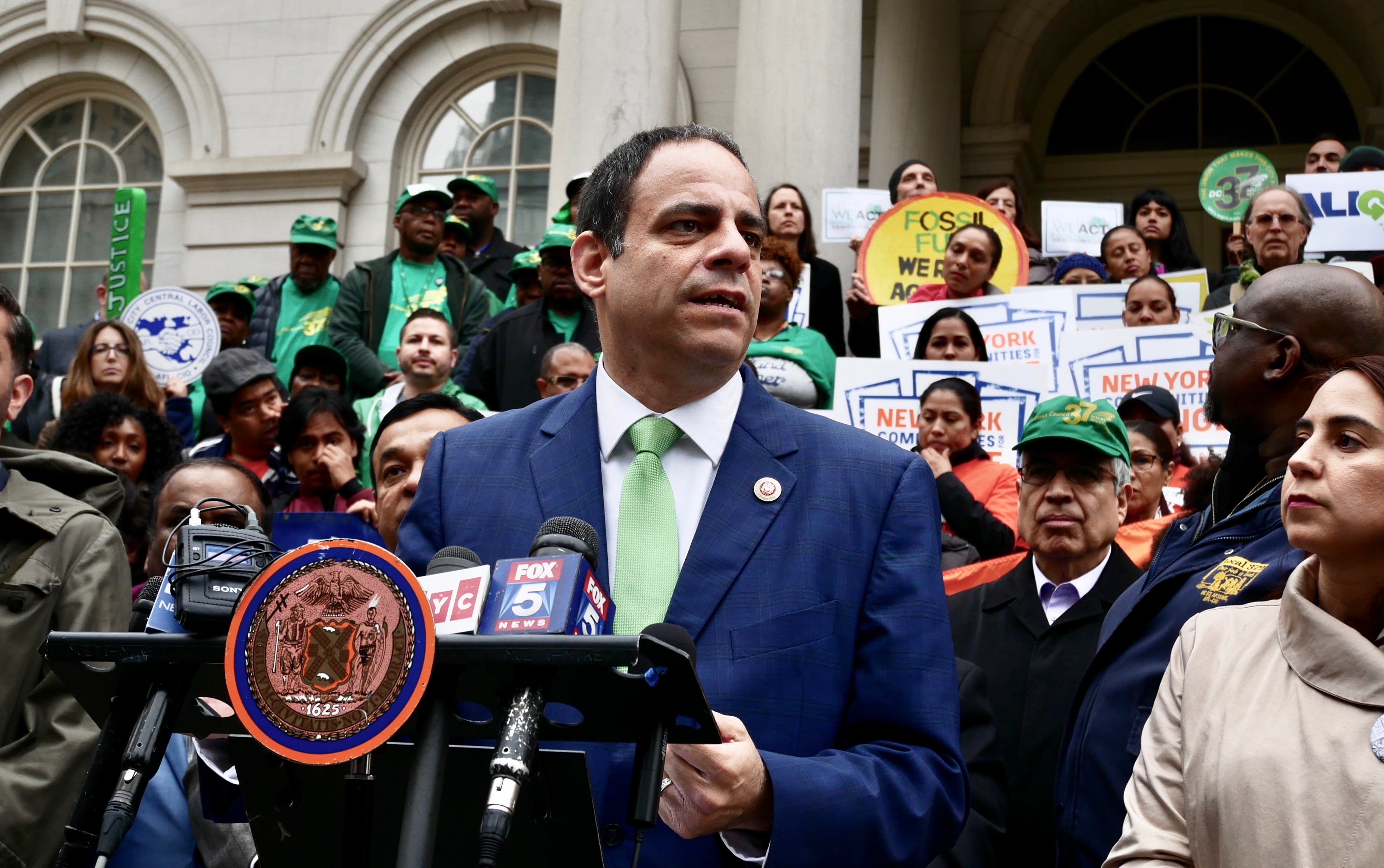

Costa Constantinides, New York City Councilman, speaking outside of New York City Hall.

Greta Moran

Of course, the new part of the Green New Deal — and regional legislation like New York’s — is that they’ve gained traction. Advocates behind the Green New Deal, the youth-led Sunrise Movement, have just launched an cross-country tour and over 100 town halls to continue this momentum. Their goal is to make the Green New Deal federal law in 2021, when they hope to have friendlier reception in the White House. But for now, local governments are leading the way. The Green New Deal is meant to be federally funded and locally implemented, points out Sophia Zaia, the Pennsylvania state coordinator for Sunrise. The Deal is meant to be a framework and funding mechanism to support regionally-driven action, rather than a blanket set of policies. So, in some sense, New York is merely jumping the gun. But New York isn’t alone. Washington D.C. recently passed a bill that would require 100 percent of the city’s energy to come from renewables. The city of San Jose has mandated that all new buildings are carbon-neutral (producing zero net emissions) by 2020, and Santa Fe has committed to going carbon neutral by 2040. As the Green New Deal meets national opposition, cities might be where climate legislation passes first.

“It’s not just one piece of legislation,” Zaia said. “It’s going to be an era of climate legislation that is finally going to tackle to this crisis.”

“We know that what that’s going to look like in each individual community is going to be different.”