Jusdevoyage via Unsplash

How COVID-19's Delta variant upended the world's fall plans

The pandemic will end eventually, but it's going to take a while

Right now, the COVID-19 pandemic news is dominated by the Delta variant of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. Delta is driving a late-summer surge in COVID-19 infections in the US and globally. Delta is listed as a “variant of concern” for both WHO and the US CDC, and it is now the predominant strain worldwide, as of August 15 representing 87.1% of infections worldwide, including 99.8% in the UK and 98.6% in the US in the past four weeks.

The Delta variant, originally known as B.1.617.2, was first reported in India in October 2020. Since then, multiple “Delta Plus” variants ave been added to the variant category (B.1.617.2.x, also known as AY.x), and to the evolutionary clade (21A at Nextstrain). Delta is described by CDC as “more than 2x as contagious as previous variants.” The population most at risk by far consists of unvaccinated people, but some breakthrough infections do occur. Viral loads are also about 1000 times higher in Delta, and there is evidence that vaccinated people can also have high viral loads and shed virus. The Delta variant has mutations that may increase its immune evasion potential, but it is still unclear whether Delta makes people sicker than earlier variants.

The Delta variant has also prompted a new wave of public health policy shifts in the US and beyond. In the US and UK, COVID policy has followed a cyclical pattern where over-optimistic declarations of impending normalcy are followed by periods of panic and scrambling to keep up with outbreaks, which in turn is followed by new periods of broad optimism and relaxing precautions, and so on.

In the US, vaccines became widely available in the spring and summer of 2021, but many eligible people did not get vaccinated. Nevertheless, there were many optimistic declarations of an imminent return of normalcy, including by the CDC. In May, the CDC surprised many people by changing its mask policy, saying that for fully vaccinated people, masks need not be worn anymore in most situations, including indoors or for large gatherings. Vaccine status was rarely checked for the unmasked, and public confrontations were common in places where people were not wearing masks, and also when they were.

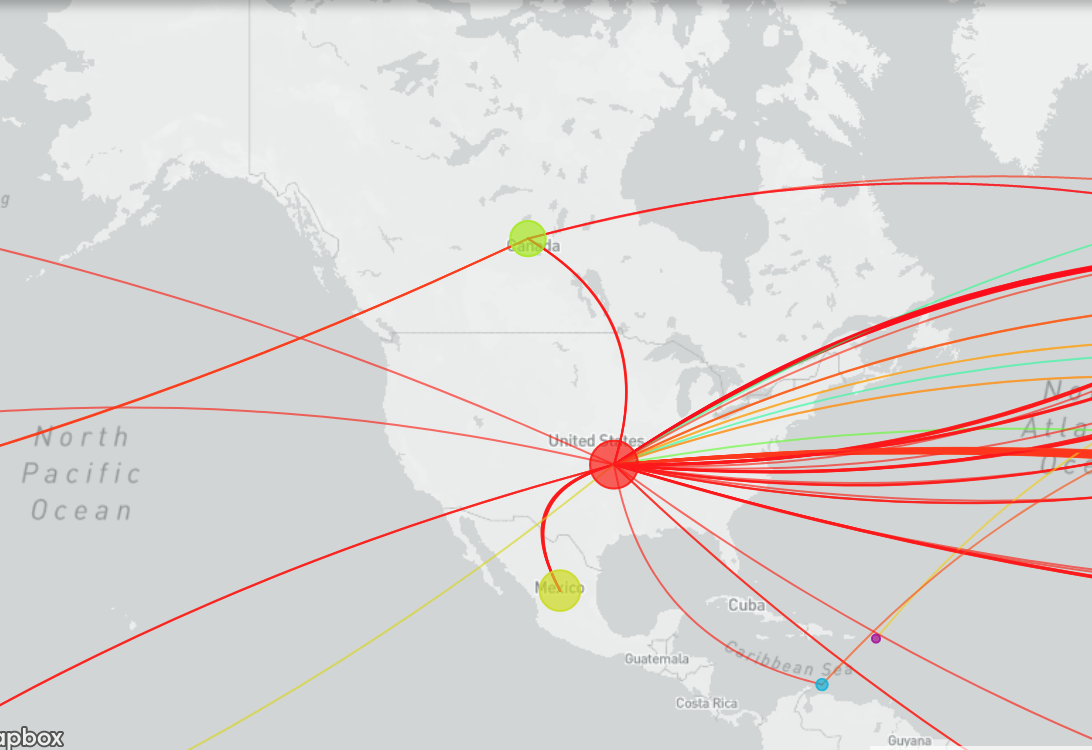

A map showing the dynamics of the Delta variant of COVID-19 arriving in the United States

Then, as the Delta surge became apparent, CDC reversed its decision for vaccinated people, once again recommending mask wearing indoors and also for children. These shifts, in conjunction with differing state regulations and conflicting messages in the media, have resulted in confusion and mistrust.

And as if the Delta variant weren’t enough, new variants are constantly emerging. Globally about 85% of people, or about 6.5 billion, have not yet been able to access to a single vaccine dose. With the sheer numbers of potential hosts still available, the virus has many opportunities to evolve into even more variants, which could be more infectious, dangerous, and/or better able to evade the immune system. Even in the US, where vaccines are widely available, children under 12 still not eligible for vaccines, and many areas continue to have low rates of vaccination and high rates of infection.

Delta carries a mutation in amino acid L452 of the spike protein that helps the virus bind to host cells. This mutation is also present in the emerging strains Kappa, Epsilon, and Iota. Gamma (P.1) is listed as a CDC “Variant of Concern” that has multiple mutations that may result in reduced neutralization by monoclonal antibody therapies, convalescent sera, and post-vaccination sera. This would mean that it is less treatable with monoclonal antibodies and better able to evade the immune system, including post-vaccination. A preliminary report based on a laboratory study has identified Lambda as highly infectious and more resistant to vaccines than were earlier emerging strains. And there are even more variants that have not yet been given Greek letter designations, including B.1.346 (Clade 20C) in Japan and B.1.1.7, which is already found in at least 167 countries.

With many worrisome new variants to come, many more cycles of panic and over-optimism are foreseeable. This remains the case even though the FDA has just granted full approval to the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine for ages 16 and above and third mRNA booster shots will soon be widely available to the US general population. Though there are reports of declining efficacy over time for the mRNA vaccines, there are also concerns that boosters are not needed for most people, and that inoculating more people is a better strategy, rather than re-vaccinating the already vaccinated.

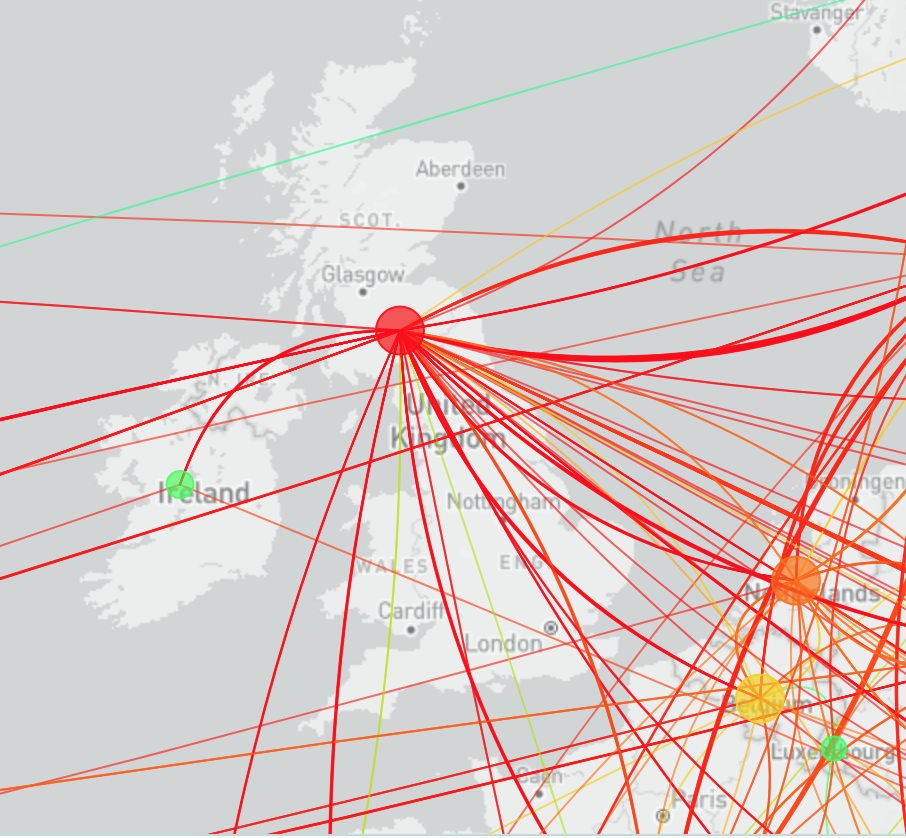

A map showing the dynamics of the Delta variant of COVID-19 arriving in the United Kingdom

The WHO expressed strong concern that more vaccines should not be given in wealthy countries since most people in lower income counties do not yet have any access. At the same time, large numbers of people in the US who do have access are simply not taking the vaccine. As a result, the vast numbers of people who remain unvaccinated make it more likely that new variants will emerge, some of which may be able to evade existing vaccines. As we have seen throughout the pandemic, strains that emerge in one place can spread across the globe rapidly, even with travel restrictions in place.

Unfortunately, boosters are also likely to lead to complacency, including relaxation of protective measures like masking and reducing gathering sizes, extensive re-opening of schools, businesses, and public areas, and more. The past six months in the US provides a clear example of how vaccine complacency works, showing how over-optimistic assumptions about vaccines can lead to the elimination of other precautions too quickly. Relying on “herd immunity,” which was already dubious even before Delta, is by now looking twice as unlikely, since the Delta variant is about twice as infectious as initial strains.

If public health policymaking remains as fickle as it has been so far, the US and UK might cycle through these extremes for months or even years to come, perhaps up until the virus becomes fully endemic and is no longer novel. As the fall approaches, with schools reopening, and considering the evidence for seasonality, another impending period of dire conditions and full panic is likely on winter's horizon.

There are already worrisome cases of school-related mass infections, including 69 outbreaks in Mississippi, where almost 1,000 students and 300 teachers and staff tested positive for COVID within the first two weeks of school reopening. In the past month, child cases have increased dramatically, rising from about 38,000 cases during the week ending July 22nd to 180,000 by August 19. According to the Policy Lab at the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, "the risk of a fall resurgence is nearly certain in northern areas" and many schools will need to rethink and improve their mitigation strategies. Another prediction based on "COVID-19 Simulator" modeling shows as many as 1600 COVID-19 deaths across the U.S. per day by the end of 2021.

By springtime, when apparent infections are likely to wane yet again, US policymakers must not relapse into wishful thinking. Policymakers at all levels must insist on caution, keep vigilant for new strains, and extend precautionary measures until there is clear and ample evidence that they are no longer needed. It is by now quite clear that public complaints and cries of inconvenience do not magically make a pandemic disappear, and too many attempts to please the public have resulted in many examples of very poor public health policy.

One of the wildest statistics in this piece is that 85% of the global population has not received a single dose of the vaccine. You do a super job of highlighting the absurdity that resource-rich nations are preparing to administer booster shots while most of the world is still unvaccinated. It seems this short-sighted strategy is doomed to fail, given that the rate at which new variants appear (and breakthrough existing vaccines) is proportional to the total number of global infections.