How did human butts evolve to look that way?

An evolutionary anthropologist tackles the mystery of the butt

Ed: Welcome to Butt Month. Every Tuesday in September, Massive will publish an article on the evolution, science, and technology surrounding the butt. If it touches the butt, we'll be covering it. Why Butt Month? Why not.

What makes humans different from other animals? Ask any ten people and you're likely to get ten different answers, ranging from our relatively large brains, to our incredible use of language and symbols, to our ability to dramatically modify the world around us.

But if you asked me, I'd say that it's our butts.

Take a look around the animal kingdom. Even our closest living relatives among the great apes (chimpanzees, bonobos, and gorillas), don't have proportionally as big butts as humans do. The main reason for this probably comes down to our unique style of locomotion. We're the only mammals alive today whose primary way of getting around is walking on two legs. And becoming upright bipeds has had some important consequences for our derrières.

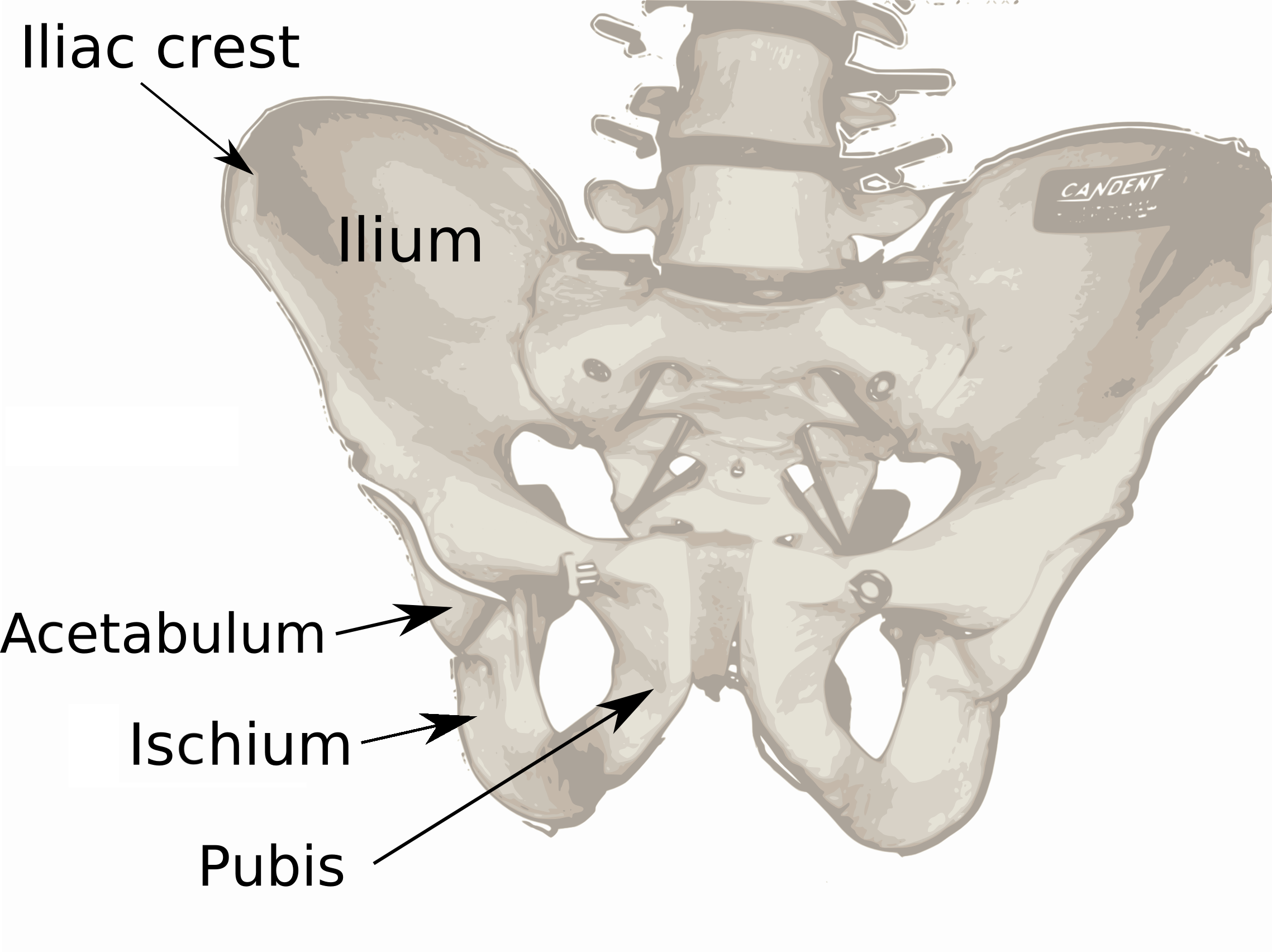

The anatomical structure that we generally think of as a "butt" is made up of adipose tissue (fat) sitting on top of our gluteal muscles, which are attached to the bony pelvis. Ultimately, it's the shape of our pelvis that dictates the shape of our butts, and that set of bones has undergone some major changes over the last six-or-so million years.

The pelvis is made up of three parts: two innominates (or "hip bones") and the sacrum. Each innominate is also made up of three bones (the ilium, ischium, and pubis) that fuse together during growth and development. And it's the ilium that's the real difference-maker between us and our ape relatives. A chimpanzee's ilium is relatively tall and flat, with the flat sides facing forwards and backwards. Our ilia, on the other hand, are short and curved around more to the sides, making our pelvis bowl-shaped. These size and shape differences are linked to the evolution of bipedalism and the reorganization of our gluteal muscles that make upright walking possible.

The three gluteal muscles are gluteus maximus, gluteus medius, and gluteus minimus ("gluteus" derives from the Latin for "butt", so that's "biggest butt," "medium butt," and "smallest butt"). Our gluteus maximus (especially the upper part) is very large compared to that of other primates. It extends the thigh and moves it backwards, and gives us power when we run or climb stairs. And it's what gives our behind most of its shape. In other apes, though, the so-called "lesser gluteals" (gluteus medius and minimus) do a lot of this work, so the gluteus maximus doesn't have to be a major player. Hence, no booty.

What our lesser gluteals are doing instead is helping our hips not drop to the side when we stand on one leg (as we do every time we take a step forward). It's the curved shape of our ilia that allows them to do that, by changing where those muscles are and, thus, their function. Our lesser gluteals provide stability rather than power.

Even gorilla butts can't compare

Nicholas Brown / Flickr CC 2.0

We can trace this change in ilium shape and inferred gluteal function throughout our evolutionary history, from the 4.4 million year old early human relative Ardipithecus ramidus (maybe — this fossil's pelvis was in pretty bad shape when it was discovered), to australopithecines like Lucy, and to Homo erectus. The ilium has generally gotten shorter, broader, and more curved over time, which means our butt has been on a multi-million year journey to becoming the lyric inspiring piece of anatomy that it is today.

The last thing that helps make human butts unique is the fat — which might also have something to do with us becoming bipeds. Humans have relatively large brains that use a lot of energy. Our bodies store energy as fat, and we have a relatively high percentage of it for a non-aquatic mammal. This has led anthropologists to suggest that our body fat helps buffer our metabolically-expensive brains against lean times. This seems to be something that we are able to do because walking on the ground is both an energetically efficient way to get around. It also avoids the downsides of spending our lives in trees — having to support all of our weight on tree branches and exist at the mercy of gravity requires a lot of energy. (Orangutans seem to do pretty well at this — but they have the strength, flexibility, and limb proportions to make it work, not to mention opposable big toes).

While all of these changes sound pretty great, our peculiarly human arrangement of muscle and fat on our backsides comes with at least one major butt-related downside: a messier pooping situation than many other primates have. Picture a quadruped, like a chimp — its trunk and legs meet up and form an angle, with the butt at the corner and its anus pointing more outward. And that opening isn't trapped between large buttcheeks. For us, there's no angle — it's just a straight line. By standing up, we've rotated the anus to point more downward, then added additional padding around it. Hence, messier pooping. Thanks, evolution.

I’m a sucker for articles on evolution and this one did not disappoint! I thoroughly enjoyed this article. It provided information about human evolution that I not only have never considered, but it also got me thinking about an area of research that was briefly touched on in this article and that I’ve always really enjoyed: the expensive tissue hypothesis (and similar extensions thereof). This area of research generally compares relative brain size of an organism to another expensive-to-produce organ or tissue in the body as a means of comparing the “importance” of each. Questions in this line of study typically ask, is brain growth more important than [insert other tissue here], and why might this be?

With the human behind being so unique in structure and what it allows us to do, I wondered how it might compare to the brain? While we have an idea of the changes of the shape of the butt from the fossil record (cool!), could we make a comparison of brain vs. butt muscle size in early human ancestry, and what might that look like? Was there a trade-off in relative size that we could equate with importance of one tissue over the other? Are there already answers to these questions? I’d love to read more on it!

Even though a trade-off between the brain and any other tissue of comparison typically exists (be it a positive or negative correlation), after reading this article I can’t help but think that the brain and the butt may have been, and likely continue to be, on par in terms of energy required to grow and maintain them since both are so crucial to daily life, albeit in different ways!