Meet Alice Wilson, the Canadian geologist who did the work of five people

She wasn't allowed to work at remote field sites, so she became the expert in her local rocks and fossils

Alice Wilson was a lot of firsts.

She was the first female geologist to be hired by the Geological Survey of Canada, to be admitted to the Geological Society of America, and first to become a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada. She mapped over 14,000 square kilometers of the Ottawa-St. Lawrence Lowlands, complete with information on the geology and fossils found in this region — and she did it alone, because the Geological Survey of Canada barred her from doing fieldwork with men.

Alice was born in 1881 in Cobourg, Ontario. Her father was a professor at Victoria University, so she was encouraged to be a scholar, but her family also greatly enjoyed the outdoors. Wilson spent her summers camping, canoeing, and collecting fossils with her family, and she developed an avid interest in paleontology. This experience provided her with skills and self-confidence that would later help her conduct geological field work.

Matteo Farinella

Wilson found her footing as a scientist in her first job as an assistant at the Museum of Mineralogy at the University of Toronto, and then, starting in 1909, as a clerk for the invertebrate paleontology section at the Geological Survey of Canada (GSC). She wanted to further her formal education but World War I, illness, and disagreeable GSC officials interfered with her plans. Wilson finally earned her doctorate from the University of Chicago in 1929. Despite this, it took the GSC an additional seven years to promote her to the rank she deserved. But other professional societies recognized her expertise, and in 1936 she was also elected as a Fellow of the Geological Society of America. She was the first woman to be selected as a fellow of the Royal Society of Canada just two years later.

Professional recognition was not the only courtesy that GSC refused Wilson; she also had to fight for the right to do fieldwork. She was forbidden to work at remote field sites with her male colleagues, so she made the case that she could work alone into the St. Lawrence Valley, an area easily accessible from her home. She successfully argued that "while not heavily built, I am muscularly very strong, and from earliest childhood have been accustomed to an out-of-door life."

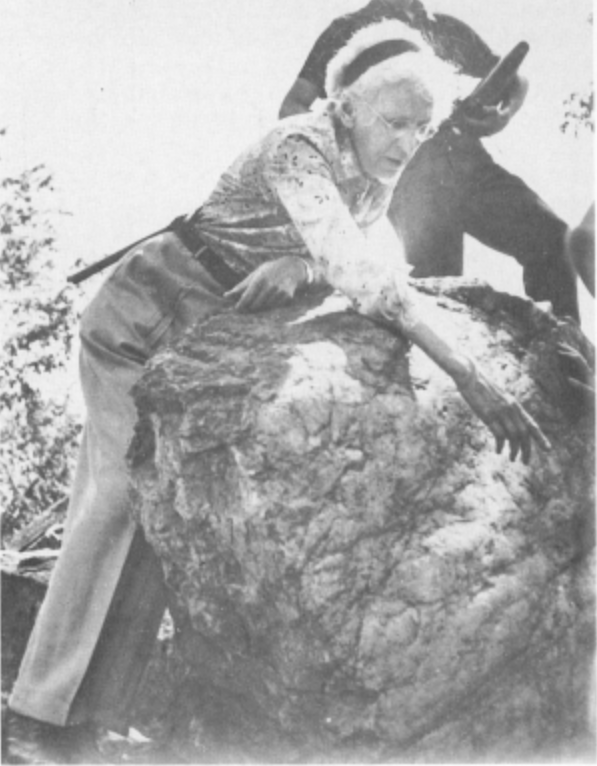

Original caption: "Alice Wilson instructing a field party."

Earth Sciences History

She explored the St. Lawrence area for the next 50 years. She covered more than 16,000 square kilometers despite her poor health and the limitations placed upon her. For example, the GSC provided all its male geologists with vehicles, but wouldn’t do the same for Alice: she had to walk or bike until she bought her own car. Nonetheless, Alice became the authority on the fossils and rocks of the St. Lawrence Valley, especially invertebrates from the Ordovician Period (444-485 million years ago). The GSC otherwise barred women from fieldwork until 1970.

Original caption: "Alice the geologist, slightly embarrassed to be posing for the photographer!"

Earth Sciences History

When she was allowed to work with other people, Wilson was an iconoclast in the field. She was famously opposed to smoking, hacking and coughing until whoever had lit their cigarette put it out. Whenever other male scientists started fighting over discoveries and things got heated, Wilson "never raised her eyes from her book, never spoke a harsh word herself."

The dedication to The Earth Beneath Our Feet, Wilson's children's book

Alice Wilson and C. E. Johnson

Alice was superannuated and forced by to retire at age 65, but she kept teaching at Carleton College (now called Carleton University) until her death. She said, “The earth touches every life. Everyone should receive some understanding of it.” She also wrote a famous children's book on geology called "The Earth Beneath our Feet," which you can read for yourself at the link. Every chapter starts with a poem, and short verse in the dedication states, "...it is not the hills but the sea that is everlasting" (an interesting thing to say since Marie Tharp wouldn't definitively prove plate tectonics until 1953, six years after the book's publication).

Wilson was such a force that five people had to be hired to replace her upon her retirement: "We never understood how she could do all she did in a day, first to the Survey, then a two-hour lecture with us, then back to the Survey, and then a field trip in the afternoon" said a colleague from Carleton.

A few months before her death, she told the Survey's director that she wouldn't need her office anymore. When told she could continue to have it, she said with finality, "No, my work is done."