.jpeg?auto=compress%2Cformat&crop=faces&fit=crop&fm=jpg&h=360&q=70&w=540

)

Christopher Collins

A version of this story originally appeared on grist

The Permian Basin is ground zero for a billion-dollar surge of zombie oil wells

Inactive wells leak methane and can poison drinking water

This story originally appeared in Grist and is republished here as part of Covering Climate Now, a global journalism collaboration strengthening coverage of the climate story.

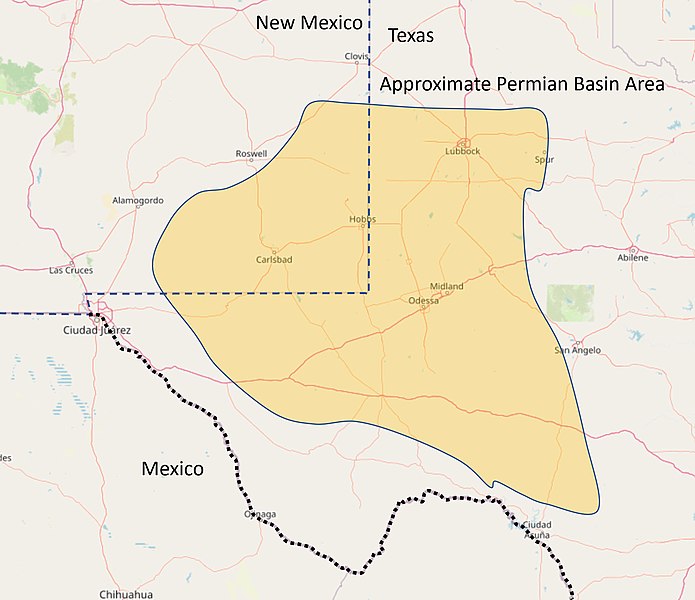

When Laura Briggs and her husband finally found their dream home in West Texas, they knew they’d be sharing space with the oil industry. The Pecos County ranch’s previous owner, local attorney Windel “Hoot” Gibson, died there when a rickety old pumpjack teetered over and fell on top of him. But sharing 900 acres with a handful of old oil wells seemed like a fair trade for a spacious ranch where the Briggs family could raise four kids and a mess of farm animals. The property is smack dab in the middle of the Permian Basin, an ancient, dried-up sea that streaks across Texas and New Mexico and is the most productive oil field in the United States. Approximately 3 million barrels of the Permian’s monthly crude production happens in Pecos County; there is an oil or gas well for roughly every two people here.

After closing on the property a decade ago, it didn’t take the Briggs family long to make the place their own. They built a roomy, two-story metal house and constructed livestock pens for hogs, goats, donkeys, and cattle. For a few years, the Briggs ranch delivered the rural splendor they’d hoped for. “When you come out here, it is dry. There is no Starbucks. But there is a peace to that,” Laura said. “This takes some stress off your shoulders and you’re like, all you really need in life is a pair of blue jeans and a good book.”

Then William “Gilligan” Sewell came along. Ever since, the family’s lives have been marred by the mess he left behind.

Sewell, a 48-year-old businessman based in Midland, Texas, founded 7S Oil and Gas LLC in 2014. In less than two years, the small-time pumping company acquired oil leases on over 18,000 acres in the region. Among them were two dozen wells on the Briggs ranch, which is just a hair bigger than New York City’s Central Park. 7S didn’t have to involve the family at all to acquire the wells on their property. In Texas, property rights are split into two categories: the land on the surface and everything underground, including oil and natural gas. When Laura bought the ranch, they only purchased rights to the surface; 7S subsequently leased the so-called mineral rights underneath.

Laura and her husband noticed that the pumpjacks on the 7S wells rarely moved much, an indication they weren’t actually producing much oil for sale. However, the family did see the wells leaking oil an gushing produced water — an industry byproduct that’s often imbued with hazardous chemicals.

One well leaked enough produced water to cover a 100-square-foot stretch of pasture. At its deepest point, the spill could have submerged a two-story building. Another well is just a 14-inch hole in the ground covered with plywood in an attempt to prevent Laura’s kids and livestock from falling in. In October, she invited a university researcher onto the property and discovered that several wells were leaking methane, a greenhouse gas more potent than carbon dioxide. A nascent but growing body of research suggests that these sorts of leaks make oil and gas wells significant contributors to climate change — especially if they’re not plugged. Leaking wells also have the potential to poison sources of drinking water.

Oil companies are legally required to “plug” their abandoned wells to prevent exactly these sorts of hazards. Drilling a well involves puncturing through layers of dirt, rock, and water to reach oil and gas deposits. The walls of the well are reinforced with steel casing and cement, but as they age — or if they were improperly drilled — cracks may form in the cement and the casings could corrode. This increases the risk of methane seeping into the air and oil migrating into the surrounding groundwater. For this reason, an operator is supposed to plug a spent well by pouring concrete into the well and also clean up the surrounding area by removing wellheads, tanks, pipes, and other unused equipment that could endanger humans or wildlife.

7S plugged one leaking well on the Briggs ranch, but took no other significant action, Laura said. In fact, the company filed for bankruptcy in 2019 after federal authorities claimed in a civil suit that Gilligan Sewell and 7S defrauded investors of nearly $7 million. In a phone interview, Sewell denied defrauding investors but refused to answer specific questions about the case, claiming he signed a confidentiality agreement. The wells are still scattered across the ranch, and though they’ve changed hands, they remain largely unplugged.

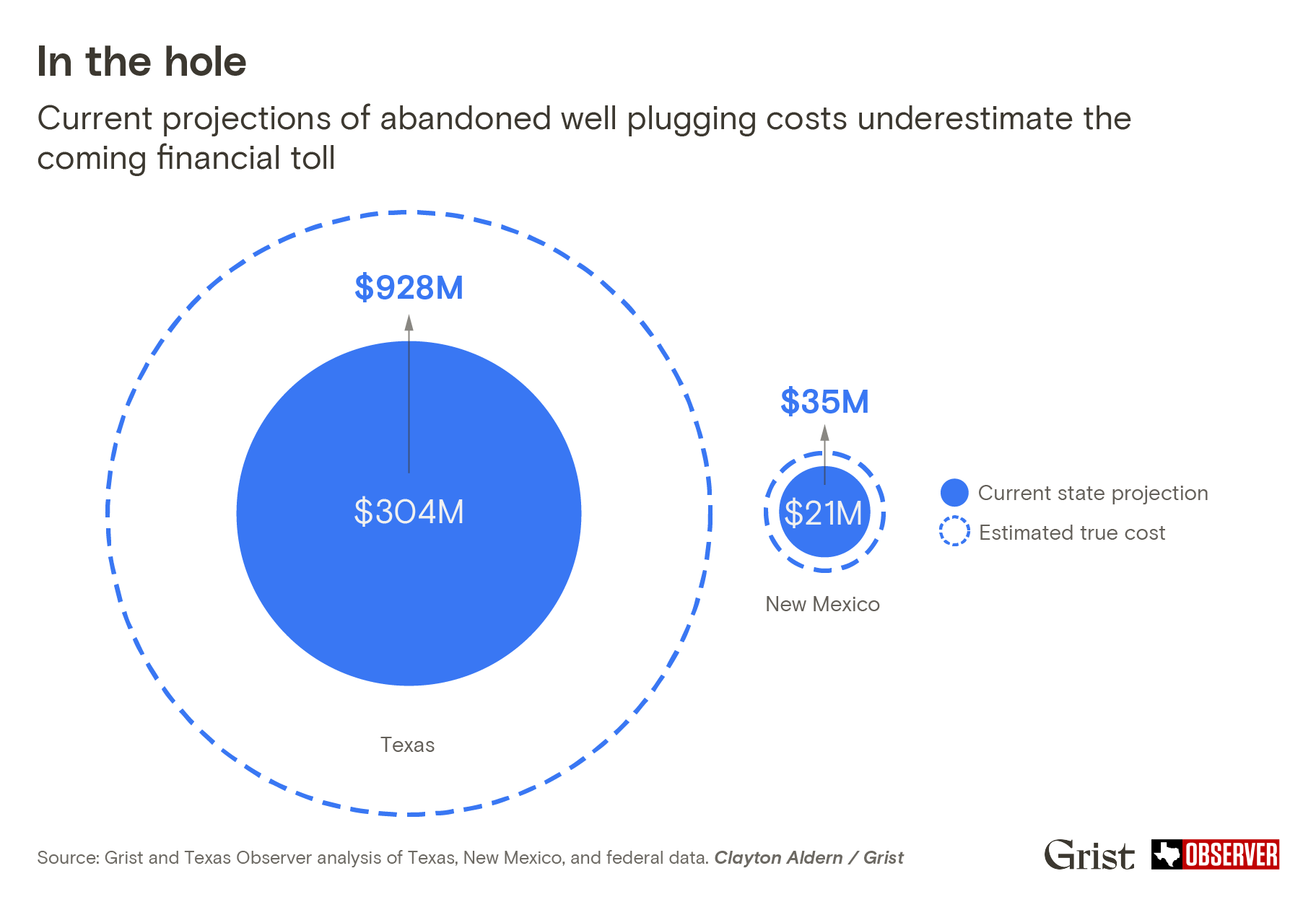

The situation isn’t much better elsewhere in the Permian Basin. Texas and New Mexico have already identified about 7,000 abandoned wells that were once operated by over 1,000 companies. State officials estimate these will cost $335 million to plug. The states define wells as “orphaned” if they don’t have an approved operator on record; additionally, Texas only includes wells that haven’t produced in at least a year. However, a healthy chunk of roughly 100,000 “idled” wells in those states could also eventually end up abandoned. (This article uses the term “abandoned” to encompass wells on the states’ orphan lists as well as inactive wells we found to be in disrepair.) Exactly how many wells will end up on the states’ rolls is an open question. While officials have argued that oil prices will eventually rise, reviving inactive wells, environmental advocates and energy analysts say that the industry is in a downward spiral that will cause the number of abandoned wells to balloon. The uncertain outlook means that independent estimates of the cleanup costs of Texas’ wells alone have ranged from a conservative $168 million to a mind-boggling $117 billion.

CritThinker on Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0)

In order to estimate the true cost of cleanup, Grist and the Texas Observer created a statistical model to identify wells soon to be abandoned, based on past trends. Our model found that approximately 12,000 Texas wells are nearly statistically indistinguishable from the more than 6,000 already on the state’s rolls. Wells our model identified have similar characteristics to wells that have already been abandoned: They’re older, haven’t been used to produce oil and gas in almost a decade, and are currently operated by younger companies with shoddy compliance histories. Given past trends, we expect these wells will be abandoned in the next four years. Texas already estimates it will cost $303 million to clean up the 6,000 wells on its abandoned wells list. State records indicate the 12,000 additional wells our model identified will cost at least $624 million to clean up. In New Mexico, our model found that 421 wells are likely to be abandoned in addition to the roughly 700 wells on the state’s list. According to state records, the plugging cost for the additional wells is more than $14 million.

States have not collected nearly enough money from operators to foot the bill. Though they force oil and gas producers to front substantial cash to cover plugging costs in case their wells are abandoned, these bonds only covered one-sixth of Texas’ cleanup costs in 2015. In New Mexico, these bonds would cover just 18 percent of plugging costs for all of the state’s orphan wells.

Spokespeople for the states’ oil and gas industry regulators — the Texas Railroad Commission and the New Mexico Oil Conservation Division — said that fossil fuel companies plug the majority of wells themselves and that state agencies only get involved in rare cases when operators disappear. The industry also funds reclamation programs managed by the states through fees and taxes, they said. Andrew Keese, a spokesperson for the Railroad Commission, said that the agency has plugged more than 1,400 wells per year over the last two years. “The Railroad Commission prioritizes protection of public safety and the environment and has a robust program of inspecting the state’s oil and gas infrastructure,” he said.

But Briggs’ experience seems to indicate otherwise. For years, Laura has dogged the Railroad Commission to help her solve the problem on her property. But officials haven’t shown much interest in helping her or anyone else trying to plug non-operational wells. Just a few miles east of her ranch, leaks from abandoned wells have formed a toxic, sulfuric lake that is three times saltier than the Gulf of Mexico. Elsewhere in the county, one well has created a sinkhole that threatens to swallow an entire highway.

“This is a failure on so many levels,” Laura said. “When you have people who are just in it for a quick buck, they don’t really care what they leave behind.”

In 2019, the 7S leases on the Briggs ranch were transferred to another operator through an arrangement that Sewell said allows him to collect on future earnings. Sewell deflected blame for problems on Laura’s property to an operator who worked there in the past. He called the oil wells a “headache” and admitted that he neither plugged the wells nor produced oil from most of them. But by using a provision in state law that allows operators to apply for multiple extensions to plugging inactive wells, he claimed he was able to offload the problem wells and stay in the oil business. The Railroad Commission would not confirm this.

“We got rid of all the wells,” he said. “We just cashed in.”

At the beginning of last year, Midland was the epitome of an oil boomtown. Interstate 20, which bisects the West Texas city of about 145,000, bustled with oil field traffic. Fast-food chains, strapped for workers, were paying employees double the minimum wage. Apartment rents rivaled those in Austin. But just a few months later, due to the combination of a worldwide oil glut and a global pandemic that severely restricted travel, Midland was more ghost town than boomtown. Restaurants and motels that once brimmed with guests mostly emptied out.

The story’s much the same just across the New Mexico border in the town of Hobbs, which serves as a mini-Midland in a part of the state some call “Little Texas.” The countryside surrounding Hobbs has been the site of intense oil production for a century. Two years ago, drilling rights here were so sought after that a single land lease was sold at auction for $101.5 million. Just like in Midland, business in Hobbs was booming until the price of oil bottomed out in 2020. The same fields where oil was reliably being pumped for decades were now home to scores of non-producing wells.

This is hardly the first time drillers have walked away from the Permian, a region with oil reserves so vast that at one point it was pumping more oil than Saudi Arabia’s most productive field. A century ago, some of the first drillers unleashed a gusher in Beaumont, Texas, and decided to see what riches lay under the sand in the western part of the state. In 1923, El Paso native Frank Pickrell tried his luck in Reagan County, an hour southeast of Midland, drilling a well he named Santa Rita No. 1. Pickrell was successful. When first tapped, the Santa Rita spewed oil sky-high and covered everything in a 250-yard area around it. His success attracted hordes of aspiring drillers to the region.

Then, in 1930, oil reserves were discovered in the Piney Woods of East Texas. Unlike the Permian’s “sour” crude, which corroded metal tanks and refinery equipment, the “sweet” East Texas product was kinder on machinery, making it more cost-efficient. “Everybody and their dog left wherever they were to go to East Texas,” said Diana Davids Hinton, a petroleum industry scholar and retired professor of regional and business history at the University of Texas Permian Basin. Just like that, the same drillers who flocked to the Permian a decade before hightailed it 400 miles east. And, according to Hinton, most didn’t bother to plug their wells before they left.

Clayton Aldern/Grist

Fast forward 50 years: Saudi Arabia flooded the market with cheap crude, triggering one of the biggest oil price collapses in U.S. history. By 1986, the price of oil had dropped nearly 70 percent, selling for just $10 a barrel. Hundreds of thousands of workers across the petroleum industry were laid off as banks called in loans and repossessed equipment. All but the most resilient oil companies went bankrupt and forfeited their assets. At the time, the Environmental Protection Agency estimated there were 1.2 million abandoned wells nationwide; many of them were left unplugged. “There were a lot of people who walked away from wells. They abandoned, but they didn’t plug,” Hinton said.

In the decades since, the abandoned wells of West Texas have been bundled and sold in bulk many times over. For instance, API #37133335, a problem well on Laura Briggs’ property, was once operated — and neglected — by 7S. The well was drilled by Windel “Hoot” Gibson’s small oil company in 1981, just a few years before the big crash. Since then, its lease has changed hands six times, according to state records. It’s been inactive for at least 18 of the approximately 40 years it’s existed.

A decade ago, the U.S. oil industry experienced a brief renaissance with the advent of hydraulic fracturing, a new technology that allowed producers to unlock vast reserves of oil once thought to be unreachable. However, the COVID-19 pandemic reduced demand for oil at a time when there was already an oversupply of the fuel, disrupting the industry to a degree unseen in decades. Small, independent drilling companies have folded under extreme financial pressure. Even the big players, such as Exxon and Phillips 66, have slashed expenses. Just like in the ’80s, a massive wave of layoffs and bankruptcies has waylaid the industry. As of December 2020, 46 North American oil and gas production companies had filed for bankruptcy. The mighty Chesapeake Energy, a publicly traded company with $8.5 billion in annual revenue and drilling operations across the country, was the biggest one to fall. Experts predict the trend will continue.

When an operator goes out of business, it’s the folks who live in the oil patch who are left with whatever mess the companies leave behind. Through the years, the Texas and New Mexico legislatures have made occasional attempts to address the growing problem of abandoned wells. The most substantial of these was in 1964 when Texas required companies to put bond money upfront to cover potential plugging costs. But even that didn’t stop the states’ ballooning inventory of orphaned wells.

Weak bonding measures, lax enforcement of environmental and permitting rules, and legal loopholes have deepened the crisis. The state agencies responsible for overseeing the industry are severely understaffed, underfunded, and reluctant to hold operators accountable for letting wells sit idle. A review of the past 30 years of state records by Grist and the Texas Observer found that the New Mexico Oil Conservation Division inspects each oil and gas well only once about every two years. After a state Supreme Court ruling limiting the agency’s authority, it did not collect any fines for thousands of violations between 2011 and 2015. In Texas, the Railroad Commission classified just 0.04 percent of violations between 2015 and 2020 as “major” — a designation that comes with fines of up to $10,000 per day — even though operators were routinely leaving wells unplugged and spilling or leaking toxic oil and gas chemicals.

Both Texas and New Mexico accept blanket bonds — a flat rate to cover plugging costs for dozens to hundreds of wells — but they often don’t come close to covering the full cost of cleanup. In Texas, producers with more than 100 wells must post a bond of $250,000. That may sound like a large sum, but it works out to only $3,968 per well for a producer with 63 inactive wells, which is the average number of inactive wells operated by the almost 1,500 oil companies with the state’s most idled wells. To put that into perspective, the average cost to plug a single orphaned well is about $30,000. When wells are inactive for extended periods of time, the states may require companies to post additional bonds, but companies can get around that requirement by simply reporting them as producing a small amount of oil or gas. Without adequate inspection capacity, the states can’t verify those claims.

In 2009, the Texas Legislature tried a different tactic: It passed a law requiring producers requesting cleanup extensions to take remedial steps, such as plugging at least 10 percent of their inactive wells each year, disconnecting electrical lines, and removing old junk left at well sites. One Panhandle rancher testified to a legislative committee that a malfunctioning electrical line running to an abandoned well on his property sparked a massive wildfire. A firefighter whose truck got stuck on a piece of abandoned oilfield equipment barely escaped the blaze; he was left with third-degree burns. Other witnesses said the legislation was a nice gesture, but it wouldn’t make producers any more accountable than they were before. Those witnesses were largely correct. Landowners in the Permian Basin would later find out that, because the statute was later weakened and did not actually require that inactive wells be plugged, the legislation did little to accelerate cleanups.

In New Mexico, several bills have been filed in the last decade to increase the maximum bond amount producers must secure. One 2015 law required a special bond to be posted for wells that have been inactive for longer than two years. At the federal level, Congress is currently considering bills that would increase bond amounts for wells on public land and provide stronger protections for landowners when leases change hands between producers. According to the Government Accountability Office, plugging wells on federal lands can cost anywhere between $20,000 and $145,000 per well. Cleaning up all 2.1 million unplugged abandoned wells across the United States could cost as much as $300 billion.

Modeling conducted for this story provides a look at the scale of well abandonments in the coming years. We used publicly available data obtained through records requests, querying databases maintained by state agencies, and the collection of county, state, and national economic indicators.

Our model identified 12,000 wells in Texas that will be abandoned in the coming years. About 40 percent of these wells are in the state’s three major shale formations — the Permian, Eagle Ford, and Barnett. According to the Railroad Commission’s calculations, about 1,400 wells will each cost more than $100,000 to plug and restore.

The Commission will have to track down more than 1,800 operators likely to abandon wells. A large number of those wells are concentrated in the hands of a few operators. The top 20 operators identified by our model will be responsible for 10 percent of abandoned wells. These operators skew younger and have been in business in Texas for about a decade on average.

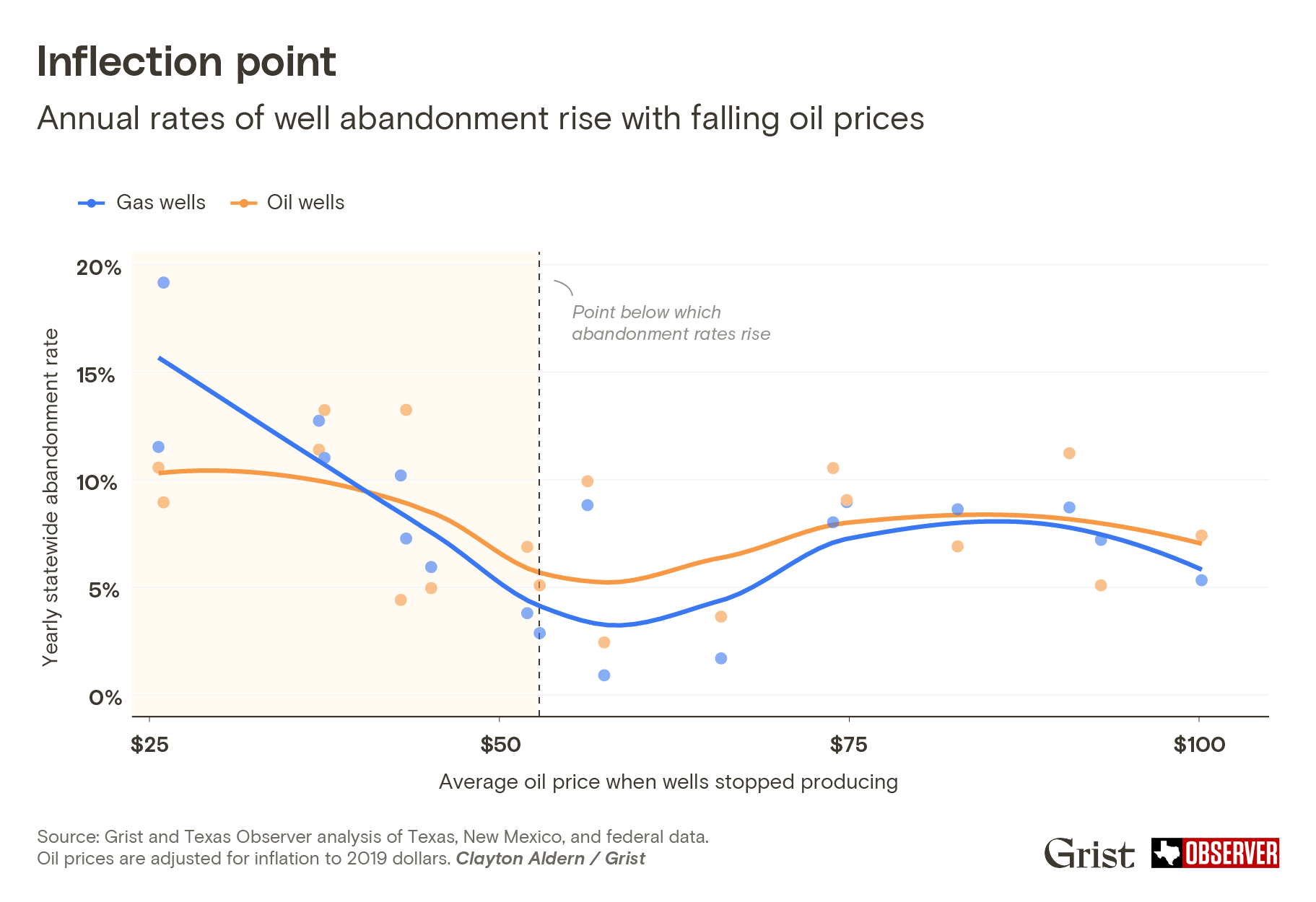

The price of oil is a strong indicator of potential well abandonment. When prices dipped below $50 per barrel, abandonments of oil and gas wells soared. The Energy Information Administration projects West Texas oil prices will hover around $50 per barrel this year and drop slightly to $49 per barrel in 2022. Any lower and Texas may see a sudden increase in abandoned wells.

The Texas Railroad Commission, the agency responsible for overseeing oil and gas in the state, did not respond to questions about our findings.

Staff at the New Mexico State Land Office, which regulates oil and gas activity, reviewed the findings and noted that several operators identified by the model were already on their radar due to spills and other violations. “We really value that [data] at the land office because it gives us an opportunity to look ahead and anticipate what kind of actions will be needed,” said Commissioner Stephanie Garcia Richard.

Bay Laxson had reached his wits’ end. The two dozen or so wells on his 1,100-acre South Texas ranch had been acquired by Jenex Petroleum and neglected by the Denver-based oil company for years, falling into further disrepair, according to Railroad Commission records. By the summer of 2016, Commission inspectors had found that 11 of the wells were not compliant with state plugging and environmental rules. Some of them had rusted wellheads and were overgrown with wild vegetation, Laxson wrote in a letter to the Commission. Leaks often sprung from pipes and pumps, spewing briney oil and water. One of Laxson’s Angus bulls had died recently after becoming entangled in some abandoned pipe and junk equipment. Its bones are still scattered on the property.

Clayton Aldern/Grist

Laxson, 71, cares deeply about taking care of his land. After a stint in the military, he returned to South Texas in the 1970s when he inherited a citrus orchard from his aunt, deciding to try his hand at organic farming. Experimenting with compost, turkey droppings, and even bat guano, Laxson’s farm soon overflowed with bower tangerines, giant watermelons, and cantaloupes. He made a name for himself, supplying watermelons to Whole Foods when it held the grand opening of its inaugural store in Austin in 1980.

Laxson ran his orchard until about two decades ago when his children moved away and rising labor costs made the farm unsustainable, but he still continues to grow fruits and vegetables on about four acres around his house. “We don’t spray anything on this place that can kill anything,” he said proudly.

So on a hot July day in 2015, when a 100-gallon chemical tank belonging to Jenex spilled onto his property, endangering the aquifer he relies on for irrigation and to water his animals, Laxson lost it. “That was kind of the last straw,” he said.

The Laxsons filed a formal complaint with the Railroad Commission and were joined by Michael Bordovsky, a landowner 100 miles northeast who was also growing increasingly frustrated with Jenex. The majority of Jenex’s wells — about 240 of them — were on his property, and they were “unsafe” and “environmentally dangerous,” he later testified before the Commission. Gauges affixed to some of the wellheads showed pressures 150 times normal levels, like ticking time bombs “ready to either vent [methane] to the atmosphere or, worse yet, break the casing and get [oil and gas] into one of the many valuable aquifers,” said Bordovsky. Laxson and Bordovsky both argued that Jenex had voided its leases by abandoning the wells on their properties, and the Commission should therefore compel the company to plug the wells and clean up the fallout.

Initially, the Railroad Commission seemed to agree, ordering Jenex to plug the wells on Laxson’s property in November 2016. Agency inspectors found that 315 wells on Bordovsky’s property had not been producing for more than a year, and Jenex hadn’t revived or plugged them. There was an open pit of polluted water near one well, which was leaking oil from its valves. Ten wells were just holes in the ground. As a result of the numerous, long-standing violations, the agency calculated a penalty of $919,430 — an extraordinary sum considering the agency’s average fine is around $2,500. To drive the point home, the agency refused to renew Jenex’s license to operate in the state, one of the last resort tactics reserved for the worst offenders.

Jenex was breaking many of the rules that were codified by the 2009 Texas law that sought to cut down on the number of abandoned wells: It had not filed forms for over 330 of its inactive wells, including many on Bordovsky’s property, to request exemptions from well-plugging requirements, according to Railroad Commission records. Some wells were missing other required forms documenting that the company had removed tanks, pipes, and other surface equipment from wells that had been inactive more than 10 years, and several failed mandated pressure tests.

Bordovsky wrote in a letter to the Railroad Commission that Jenex was reporting several wells on his property were producing oil when they weren’t outfitted with pumps. In fact, they could barely be located because of the overgrown weeds surrounding them. Bordovsky claimed that by reporting the wells as producing, Jenex could avoid having to post additional bonds for cleanup, another requirement under the 2009 law. State inspectors never bothered to perform site checks to verify whether the wells were producing; they simply took the company at its word. Bordovsky took photos of the nonfunctioning wells and sent them to the Commission, which did not investigate.

Facing an almost $1 million fine and the loss of its license, Jenex performed an end run around the agency by finding a buyer: Maverick Energy. It was a familiar name for Bordovsky, who was then forced to drop his complaint against Jenex. Maverick had operated the wells on his property until 2012. But when one of several companies run by Maverick’s directors filed for bankruptcy, Maverick’s leases ended up with a court receiver. Jenex then acquired the leases. Bordovsky was livid and filed a subsequent complaint with the Commission arguing that the agency shouldn’t allow Maverick to operate the wells.

During a 2017 administrative hearing, Jenex told the Commission it could either allow the transfer to proceed so that Maverick would become responsible for the wells, or block the transfer and deal with a $5.5 million cleanup on Texas’ dime. “If [the permit] is not renewed,” a lawyer for Jenex said, “all of this will become the state’s problem.”

Despite Bordovsky’s protest, the Commission approved the transfer of the lease, with strict conditions. Maverick was required to bring its wells back into compliance within three months. Three years on, that hasn’t happened. Last year, Maverick racked up 121 state violations for infractions such as disposing of oil and gas without a permit or not plugging inactive wells. The wells on Bordovsky’s property, which were producing more than 550 barrels of oil per month in 2014, were producing no oil as of the end of last year. Maverick was briefly barred from operating in Texas, but the Commission renewed its license last year. Meanwhile, the agency dropped enforcement charges against Jenex. Once the wells were transferred to Maverick, Jenex was no longer an operator in the state of Texas, and the fines were erased.

Keese, the Railroad Commission spokesperson, said that the agency performed multiple checks before approving the sale, including verifying that Maverick posted the blanket bond of $250,000 required under state law. When violations weren’t addressed promptly, the Commission severed Maverick’s leases, prohibiting the company from operating in the state until it addressed all outstanding violations and paid any fees that were due. Keese said the agency is monitoring the company for continuing violations and may take further action if it fails to comply with state regulations. Requests for comment from Maverick directors were either declined or not returned.

After taking over the leases in 2017, Laxson said Maverick was diligent about fulfilling its promises to him. He’d been particularly worried about several non-producing wells leaking into the aquifer he taps for irrigation water. Over two years, the company plugged two high-risk wells; a cleanup worker told Laxson it cost at least $100,000 to plug just one of those. Then, things took a turn for the worse.

As the novel coronavirus spread to the United States, oil prices plummeted from about $63 to less than $20 per barrel last spring. Operators shut down half of all producing wells in Zavala County. Given the remote location of Maverick’s wells — Laxson’s ranch is closer to Mexico than it is to Austin — haulers charge $5 per barrel just to drive the oil to processing facilities, Laxson said. He added that his royalty checks have shown the company selling oil for as low as $12.30 per barrel. His share came out to about $1.20 per barrel.

Now, Laxson is worried about what might come next. Maverick is among the top 20 Texas operators with the most wells likely to be abandoned, with 57 of its approximately 300 wells forecasted to meet that fate, in part due to the company’s long history of rule-breaking. Our model also identified two other operators — run by the same people and registered at the same address as Maverick — likely to abandon more than 40 wells each.

Laxson thinks the chances of another well being cleaned up on his property are slim and is treading gingerly with Maverick. He even performs small repairs on the wells himself, tightening valves on pipes.

“[Maverick is] at the point now where they’re pretty close to throwing their hands up,” he said. “And what happens then? The old lease is just left in limbo, nothing gets done, and it falls to the state of Texas. And the state of Texas is not going to do anything.”

It’s a scorching afternoon in mid-July, and Ty Edwards drives his pickup toward Imperial, Texas, a tiny community at Pecos County’s northernmost fringe. “Here’s the sinkhole,” Edwards says suddenly. “You see the highway sagging down?” As if on cue, the truck and its passengers start leaning ever so slightly to the left. The tilting highway comes courtesy of a caved-in abandoned well underneath it, Edwards explains. He turns onto a dirt road leading to Pecos County’s most infamous landmark: Boehmer Lake, a 2,000-foot-wide deadly pool of putrid water. That too is a legacy of the county’s widespread abandoned well problem. The place reeks of sulfur, and a nearby sign cautions travelers about poisonous gas.

.jpeg)

Ty Edwards holds his shirt over his nose as he approaches an oil-sheened pond created by an abandoned well in Pecos County. Edwards has been trying to raise awareness about these wells for almost a decade

Christopher Collins

Edwards, the general manager of the Middle Pecos Groundwater Conservation District, stops the truck at Boehmer Lake’s shore and hops out. He gingerly navigates a land bridge leading into the lake’s interior, stepping over a javelina skeleton en route. “Probably drank this water and died,” he said.

Here, about a dozen abandoned oil wells drilled during the first West Texas oil rush in the 1930s and ’40s have caused massive contamination. For miles around the site, long-idled wells have generated goopy, oil-sheened ponds that may be tainting water sources.

While studies on groundwater contamination from abandoned wells are few and far between, the research available points to a fairly widespread problem. A 2011 report from the Ground Water Protection Council, a nonprofit group run by state regulators, found that about 15 percent of all instances of groundwater contamination recorded by the Railroad Commission between 1993 and 2008 were a result of oil and chemicals migrating from orphaned wells.

Researchers are also beginning to quantify the amount of methane escaping from orphaned wells — and accelerating climate change. In 2016, University of Cincinnati researcher Amy Townsend-Small found that 40 percent of inactive or abandoned wells she tested in Colorado, Wyoming, Ohio, and Utah were emitting methane. The EPA used her research to estimate that the nation’s approximately 3.1 million abandoned wells were spewing greenhouse gas emissions equivalent to burning more than 16 million barrels of oil.

After Grist and the Texas Observer introduced Townsend-Small and a research assistant to landowners with abandoned wells on their properties, the researchers conducted what they believe is the first-ever academic study of methane emissions from abandoned wells in Texas. They spent three days surveying 40 wells, most of which were on Laura Briggs’ property or around Boehmer Lake. Their research, which was recently published in the scientific journal Environmental Research Letters, found that nearly half of the wells were leaking methane. The three largest emitters were responsible for more than 90 percent of the total methane emissions. Researchers call these “super emitters,” and they’ve found that they’re responsible for the vast majority of abandoned well emissions elsewhere in the country, too.

.jpeg)

Townsend-Small and Hoschouer surveyed 40 wells in West Texas and found that nearly half were leaking methane, a potent greenhouse gas

Christopher Collins

A week after Townsend-Small discovered methane leaks at Briggs’ wells, Laura decided to follow up. In an aging Chevrolet Suburban with a “Girls Just Want to Have Fun” bumper sticker and painted flames on the hood, Laura and her 12-year-old son cruised down a bumpy dirt road, trying to locate the worst of 7S’s leftover abandoned wells. A motley crew of farm dogs flanked their vehicle.

“We’re looking for the next well on the right,” she said. Her son leaned out of the car window to get a better view. They soon found the well site, marked by an unmoving tan pumpjack and a wide concrete foundation. The well was drilled in 1981 but likely hasn’t produced a drop of oil since at least November 2017. Nevertheless, the agency does not consider the well abandoned.

“This one they’ve had problems with in the past. It used to gurgle up,” Laura said. It still is gurgling, apparently — that day, the well was leaking crude onto the gravel below and filling the kinks of the pumpjack with oil. Tiny gas bubbles formed and broke where the joints met. Laura pointed to a site just across the road where she says 7S once operated a pit to hold oilfield wastewater. One time, the chemical-laden water flooded the road all the way back to the Briggs home. Laura said 7S removed the pit, but in the process the company left a hulking mound of dirt in the middle of a pasture. Now the family uses it as a backstop for target practice. The experience sums up the family’s plight: They try to make the best of a bad situation, but there’s simply not much they can do to hold the industry accountable.

“When you have a bad horse, you put him in the round pen and you make him run circles until he stops kicking,” Laura said. “I’m just going around the pen.”