Lab Notes

Short stories and links shared by the scientists in our community

Millions of people all over the world are searching for their romantic partners online, using dating apps. To find a match, dating apps use algorithms to fish through hundreds of profiles so you don’t have to. But, like all algorithms, they aren’t perfect. Here to expose the pitfalls of online dating is MonsterMatch.

In MonsterMatch, you design a monster and their dating profile. Then the simulated dating app experience begins, in which you can swipe left or right and “message” with other monsters. Just like real dating apps, MonsterMatch uses an algorithm called collaborative filtering to decide which profiles to show. Collaborative filtering works by taking your data - a left or right swipe - and matching it to data from previous users. The app will then show you another profile that was popular with people whose swipes agreed with yours.

The problem with collaborative filtering is that it is heavily influenced by the first users. In the game MonsterMatch, this algorithm assumes that you like and dislike the same monsters as some of the early players. The monsters it shows you will start to be very similar to each other - a selection from the most popular monsters chosen by previous players.

In dating apps, the algorithm assumes you like and dislike the same people as previous users. Your first swipes can effectively pigeonhole you into a clique of users. If the clique says “No, we don’t like this profile,” then you will never be shown that profile. The clique filters which profiles you see, and therefore which people you date. This seems rather restrictive, given that dating is a tricky science.

So the next time you open that dating app, consider how collaborative filtering influences whose profiles you view. To maximize your dating app success, notice when the profiles you are being shown lack variety - the collaborative filtering algorithm may have pigeonholed you. Try to reintroduce variety into your online dating search by experimenting with other available app features.

You can play MonsterMatch here. In just a few minutes of swiping, you will discover the patterns, biases, and pitfalls of collaborative filtering for yourself.

Secretservgy on Wikipedia

I’m conducting fieldwork in a state park when a perfume-like smell fills the air. I instantly recognize the soft white petals, reminiscent of the roses that belong on prom corsages. As much as I shouldn’t, I find myself enamored with Rosa multiflora, a plant that goes by the common name of multiflora rose.

Despite its charm – or rather, because of it – this rose is a highly invasive plant. As a forest ecologist studying forests post-disturbance, I often shake my head when I see invasive plants planted in garden beds or used in wreaths. But in the field, it can be hard to not love a rose amidst the tangles of poison ivy.

Lionfish are another highly invasive species

The stark presence of the rose in the forest reminds me why this process happens, and the dangers associated with invasive plants particularly for forest health. In our global society, plants are constantly being traveling around the world through trade and as stowaways on shipping pallets, boats, and even on hiking boots.

In a forest, native plants are subjected to increased competition from invasive plants that often results in diminished biodiversity and forest cover. Invasives are a huge economic burden to homeowners and the subject of many state and government programs. Climate change is also predicted to increase the range and threat of many invasive species.

Many state parks and conservation groups host removal days or invasive initiatives and there are sources online to determine what species threaten your neighborhood. Learning what belongs – and what doesn’t—in your backyard is the first step to protecting forested ecosystems.

Photo by h heyerlein on Unsplash

In a paper published in the journal Neuron this month, neuroethicists outline four ways that neurotechnology companies marketing wearable brain devices to consumers claim that their products positively enhance users' cognitive abilities and overall individual well-being.

Despite these promising claims, to date there has been very little research into the effectiveness, benefit, and safety of similar direct-to-consumer brain devices. This is particularly concerning since individuals might resort to these wearable neurotechnologies instead of seeking necessary medical care. This is even more problematic in the case of children, where we are not able to predict the effects of those devices on their brain development. What can be done?

The authors suggest that these companies should highlight the negative side-effects of the marketed brain devices in a more ethical and sensitive way. One way to achieve this could be through the addition of a warning label communicating the potential side-effects as well as the fact that there could be other unforeseen negative health consequences to the purchaser. And when it comes to data privacy? We should definitely start asking those questions.

Photo by Diana Parkhouse on Unsplash

Carbon capture is often suggested as a necessary solution to prevent impending climate disasters. But, what exactly is carbon capture, and how does it work?

Carbon capture is a distinct part of a larger process known as carbon capture and storage. This process includes literally capturing the carbon dioxide as it is created in power plants or other industrial activities. Then it is transported by pipeline or ship for storage underground in places like former oil fields.

Nature's carbon capture and storage method

Photo by Casey Horner on Unsplash

The Center for Climate and Energy Solutions notes that the carbon capture and storage process is a practical and productive method of reducing greenhouse gas emissions, achieving 14 percent of the world's emission reduction targets by 2050. Captured carbon can even be used in fuel manufacturing and oil recovery, making these industries a bit cleaner.

In our current timeline, where the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has already released a special report on Global Warming of 1.5º C, I would argue that carbon capture solutions are a necessary solution to driving down rising global emissions that threaten daily life.

Axios has just published an immensely helpful illustration of the ways carbon can be captured, from trees and soil to highly-touted technological solutions. Check it out while enjoying a cold beer brewed with recaptured carbon!

Photo by Richard Lee on Unsplash

Every year monarch butterflies in southern Canada and the north-central United States travel over 4,000 kilometers (2,485 miles) southward. Triggered by cool weather and the slow death of their host plant, milkweed, monarchs make their long journeys to the oyamel fir forest in Mexico. However, this stunning migration is at risk. The population of monarchs in California alone has declined by 86% between 2017 and 2018.

Monarch butterflies face a wide range of threats including bad weather, climate change, and exposure to chemicals and contaminants, as well as the dual dangers of predation and pathogens. Deforestation in Mexico where the butterflies overwinter and the loss of breeding habitat and milkweed on the northern breeding range also pose significant risk at different stages in the monarch life cycle. Despite mounds of research in each of these areas, it turns out that we still don’t fully understand the contribution of each to monarch declines.

To answer this question, my colleagues and I examined 115 peer-reviewed papers, classifying them by the type of risk and whether the potential threat currently had a positive or negative effect on monarch butterflies. Using papers with multi-year datasets or results from predictive models, we also assessed whether each threat is thought to pose a continued risk to the population (as opposed to a one-time problem). We found that poor environmental conditions and loss of habitat in Mexico and on the northern breeding grounds are the most severe threats to monarch butterflies. With this in mind, researchers can design studies and conservation interventions that that directly address these threats to reduce the decline of this charismatic species.

Yann Caradec via Wikimedia

All Caster Semenya wanted was to “run free” in the body she was born with. As a two-time Olympic Champion, she is a dominant force in the international athletics scene, specifically in the 800m race. Last month, the Court of Arbitration for Sport ruled in favor of a motion put forward by the International Association of Athletics Foundation (IAAF). This movement banned Semenya, and others with natural conditions, such as the hyperandrogenism Semenya has, which lead to high levels of testosterone. If they wanted to continue to compete in international competition, then she would have to take testosterone-suppressive drugs to lower her natural levels of testosterone to a level deemed “normal” for female athletes.

A second appeal to the Swiss Supreme Court has finally lifted this ban after what seems like a nightmare year for Semenya and other afflicted athletes. Although this is a temporary action, the lift will remain in place until Semenya’s case can be fully evaluated by the Supreme Court. This could take a year or more to evaluated and gives these athletes a second chance to race!

This is certainly a step in the right direction. However, Semenya’s fight is not over. She will have to defend her case once again and be subjected to intensive questioning and demanding court appearances. The implications of this ruling impact our cultural understanding of gender, sex, and sport. It is crucial that we understand these concepts and fight for true equality. Most importantly, Semenya is back in competition in the body she was born to run in.

Photo by Drew Farwell on Unsplash

After spending the first few years of life in fresh water, young Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) undergo a complex series of physiological changes that allows them to better withstand the high concentration of salts as they migrate to seawater. Young salmon tolerate the salts in the environment through the development of cells, called ionocytes, that secrete sodium and chloride and a specialized enzyme that acts as a pump to transport these electrolytes.

Landlocked salmon, on the other hand, remain in freshwater and it is unknown if, over time, this has resulted in physiological differences compared to salmon that migrate between freshwater and seawater over their lifecycle (anadromous). So, Dr. Stephen McCormick of the US Geological Survey led a team to investigate if there was a difference in expression of the enzymes responsible for salt transport, as well as the underlying hormonal regulation, between the two types of fish.

McCormick and his team brought salmon into the laboratory to monitor their responses to controlled changes in the environment. They found that levels of an enzyme that allows the fish to live in salty environments and the hormones responsible for regulating seawater acclimation, like cortisol and growth hormone, were higher in anadromous salmon than landlocked fish. These findings shed light on the complex physiological changes that occur during sea-going salmon development as well as how these salmon populations have evolved over the last 14,000 years.

OH MY GOD DOUBLE ASTEROID ALL THE WAY ACROSS THE SKY

what does it mean??

European Southern Observatory (ESO)

Okay "all the way across the sky" really means they got 5.2 million kilometers away at their closest. But still, double asteroids!!! Look at 'em. The International Asteroid Warning Network (IAWN) and the European Southern Observatory's Very Large Telescope (VLT, actual name) spotted Asteroid 1999 KW4 in late May. Here's a NASA .gif of the asteroid, which has two parts (making it a "binary" asteroid). Alpha is the bigger one, the "primary" body, and Beta, the smaller one, is the secondary body but is also sometimes adorably called a "moonlet."

(NASA/JPL)

Although 1999 KW4 isn't a threat, since the closest it came to Earth is 15 times further away than the Moon is, it's being treated as a kind of rehearsal for observing other potentially dangerous objects. 1999 KW4 is also reminiscent of Didymos, another binary asteroid (its moonlet is called Didymoon). NASA will be attempting to deflect Didymoon in 2022, to see if changing an asteroid's course is possible. I'm already working on my screenplay.

Where ever humans have gone, so have dogs – a mutualistic relationship that has left co-evolutionary traces in their brains, behavior, and bodies. However, despite dogs’ ubiquity in human societies, keeping dogs is not a universal trait among individuals. Is the predilection for canine company purely an acquired taste, or might dog-keeping also be written in the genes?

According to a recent study, maybe there's something in your chromosomes. Genes wield significant influence over whether someone is a “dog person,” with over half of variation in dog ownership explainable by heredity (which means the other half of explaining why someone does or does not have dogs is explained by something else).

The authors relied on powerful data sets to analyze dog ownership in 35,035 twin pairs: the Swedish Twin Registry (the largest twin cohort database in the world) and dog registration records from the Swedish Board of Agriculture and Swedish Kennel club (estimated to account for 83% of the country’s dogs, due to national laws requiring their registration).

This study is the first to suggest that dog ownership has a notable genetic component, heritable by 57% for females and 51% for males. Identical twins were found to be more likely to own dogs than non-identical twins – offering evidence that genetic factors play a role in that choice, since identical twins share their entire genome and non-identical twins share only half.

To be clear, this is pure correlation. No responsible “dog owning” gene has been isolated, but these findings tap into the biggest questions surrounding domestication: not just how, but why, did it happen? A genetic component offers new pathways for probing these layers.

Guido Gautsch on Wikimedia Commons

Sea wasp, marine stinger, common kingslayer. The nicknames for the various species of box jellyfish's stem from this animal's reputation as one of the most dangerous creatures in the sea. These jellies, which are in the class Cubozoa, cause agonizing pain when they eject their venom and can even kill humans.

A group of Australian researchers from the University of Sydney, led by Dr. Man Tat-Lau recently identified a potential antidote to box jellyfish stings. They used genetic editing tool CRISPR to knock out over 19,000 genes one by one in human cells. Box jellyfish venom normally kills cells, so the researchers wanted to see whether any of these modified cells could survive after exposure. Two genes required for the venom to inflict such intense pain jumped out at them.

One of these genes directs production of cholesterol. The researchers performed experiments to tell whether drugs that reduce cholesterol signaling could serve as an antidote to venom poisoning. Treatment led to less cell death in human cells, and mice showed reduced symptoms of pain.

With this antidote, victims of a box jellyfish sting may one day only need to apply a drug to treat their pain. Understanding how the venom acts on cells will also provide a starting point for studying pain pathways and using venom components to develop new medicines.

There's life in one of the hottest, saltiest, most acidic, most contaminated places on Earth

And the scientists who found it got pictures

A. Savin via Wikimedia Commons

The Dallol geothermal area (14°14′21″N; 40°17′55″E) in Ethiopia is hell on Earth. The boiling water of the hot spring is three times saltier than the ocean, contaminated with heavy metals, and has a pH of zero. It’s ten times more acidic than battery acid.

And yet, something lives here according to a new study in Scientific Reports.

Curious about the limits of life on Earth, a team of researchers put some salt-encrusted rocks around the hot springs through a filter and tried to extract some DNA. They got a hit - the DNA was very similar to a group of organisms called Nanohaloarchaea, some of which live in high salt environments.

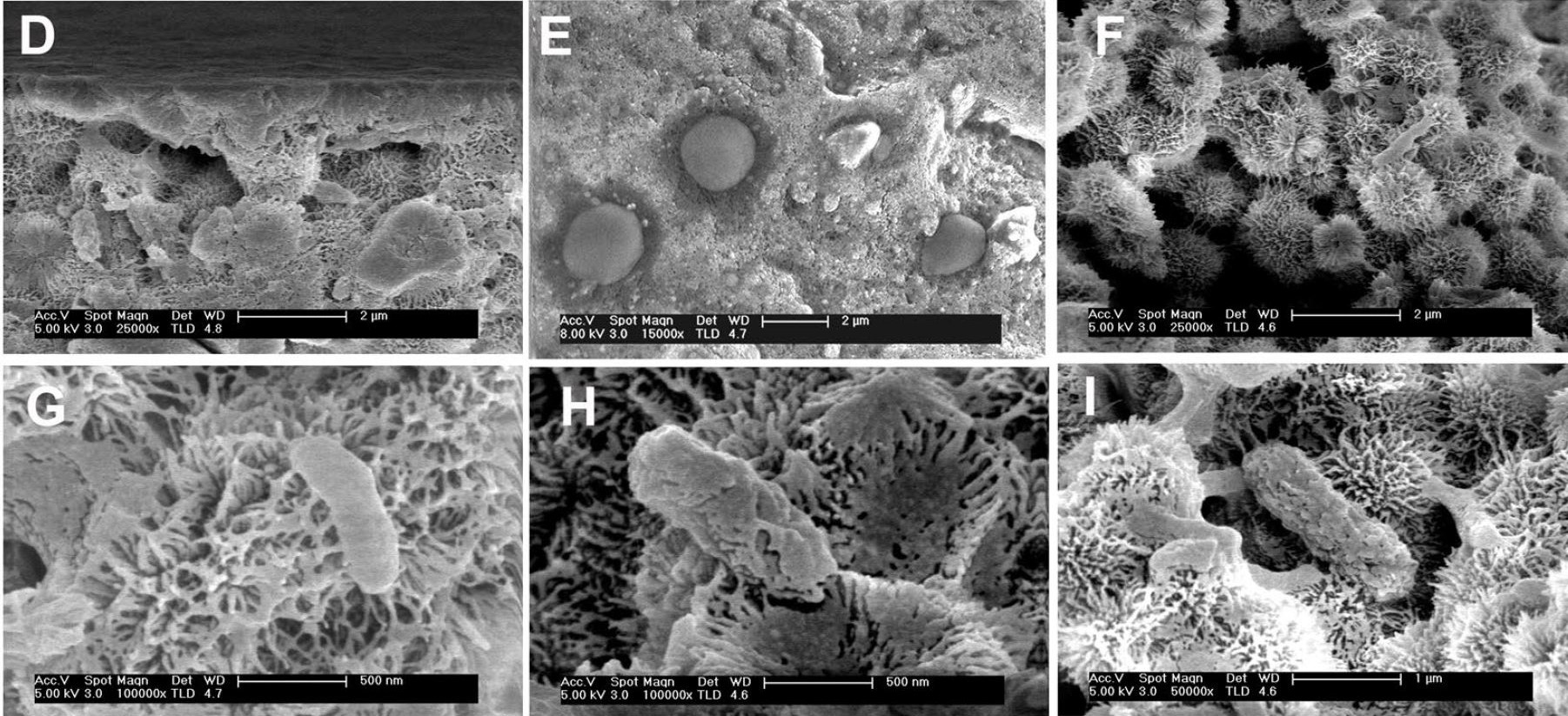

What did these mysterious Nanohaloarchaea look like? The team put their samples under some very powerful microscopes to find out.

Pill-shaped micro-organisms within a network of thin, needle-like crystals. Notice how the crystals have grown around and encapsulated the microorganisms.

Gomez et al. in Scientific Reports

Now that we know that they’re here, I can’t wait for someone to figure out exactly how these ultra-small microorganisms survive, and what they mean for the ecology and geochemical cycling of these hot springs.

The authors suggest this has implications for finding life on Mars. It doesn’t seem so far-fetched.

Photo by Alakh Dave on Unsplash

With current extinction rates 1000 times higher than natural background extinction rates, our planet is heading towards a biodiversity crisis similar to that which occurred after the disappearance of the dinosaurs and over 75 percent of the known species on the entire planet. The only way for animal populations to survive this death sentence is to be best suited for their environment in a way that ensures not only their survival, but the preferential survival of their offspring as well. Biologists refer to this as "fitness."

A new study from the University of Southampton challenges what we think of when we hear fitness. The researchers predicted that over the the next century, the body masses of animals will decrease as natural selection favors smaller birds and mammals. This specifically applies to animals that can live in multiple habitats and are extremely fertile, like rabbits and songbirds. In fact, the overall body mass of animals is predicted to decrease by 25 percent before 2219. This is bad news for large animals and species that occupy very specific niches, which includes keystone species such as sea otters and wolves. These are called keystone species because they play a critical role in shaping and maintaining their ecosystems.

Birds and other fast-reproducing organisms are predicted to shrink over the next 100 years

Laura Wolf / Flickr

Unsurprisingly, the cause of this downsizing is humankind - specifically our continuous impact on our planet through climate change, habitat destruction, and hunting and farming. However, there is a point of hope. If conservation actions can be taken to protect those keystone species that we know are threatened, we can perhaps reverse the short-term death sentence and prolong these important ecosystems.

This is not a new message. However, the range of threats that species face - and the myriad forms they take - make swift action an urgent necessity.

Thinking about releasing thousands of balloons for your local Indy 500? That's littering

The balloons are supposed to be biodegradable but they're really not

What counts as littering? Some signs of littering might be obvious, like the 20,000 pounds of trash collected on Virginia Beach after the Memorial Day weekend. But strictly speaking, the definition depends on the country and state. In some states in the USA, the weight or type of litter determines the severity of the crime. Penalties for littering can also depend on state, ranging from $20 in Colorado to $30,000 in Maryland. Indiana, USA defines littering as the intentional placement or leaving of “refuse on property of another person.” You are caught flicking your cigarette from a moving vehicle? Littering. You dump a bag of trash on the neighbor’s lawn? Littering. And in Indiana, you can be charged a fine up to $1,000 that qualifies as a Class A infraction.

What about releasing thousands of balloons, like at the Indy 500 in Indianapolis, Indiana on May 26, 2019?

Balloons seem festive and innocent enough, especially when used for birthdays, graduations, and general well-wishing. But released into the air, balloons pop in the thinning atmosphere and fall back to earth. That’s when balloons turn into their evil counterpart. Balloons strings entangle animals and they mistake them for food, trying to swallow them and then becoming a choking hazard. In a recent study, researchers reviewed how plastic pollution contributed to >1700 seabird deaths and found that balloons pose the highest risk to seabirds of all ingested debris. Sea turtles, too, are particularly threatened by balloon littering because the soft plastic resembles a food item, jellyfish.

The balloons released at the Indy 500, “reported as 100% biodegradable”, are not*, in fact, biodegradable. Although more brittle, many balloons were still intact after a test of 11 months in the natural environment. If a balloon pops and falls on property in Indiana, by the state law, that should qualify as littering. But for a larger corporation littering with thousands of latex balloons, the fine should be higher. We can do better for the environment and a higher fine for littering might be the economical motivation to rethink next year’s Indy 500 balloon release.

(*Disclosure: The Indianapolis Star reporter, Emily Hopkins, who did this experiment is engaged to Massive founder Allan Lasser)

The Atlantic magazine recently published another article about the replication crisis, focusing on why disproven research is still studied. The fields of science are littered with what Steven Poole refers to as "intellectual zombies," disproven ideas that refuse to die.

An illuminating example are 18 candidate genes that are ostensibly linked to depression, which upon a second, more thorough look may have nothing to do with depression at all. These genes have been heavily researched, all based on foundation of research that turned out to be nothing more than sand.

Graduate students are uniquely harmed by these unreplicatable experiments. While there are real fiscal and societal costs, there are also unseen personal costs. The “waste of 1000 studies” is a waste of many more years that graduate students spent trying to make these experiments work.

We have five or so years to learn and work on a project. And critically, we often have five years to publish said project. If you’re starting a project on a foundation that doesn’t exist, you’re set up for failure. And in cases like the one the article discusses, where the evidence seems strong, that failure feels so personal. The logical assumption is that it’s your fault, as the lowly graduate student.

It can get worse when the thing you’re seeking to build off and replicate is from past research in your own lab. Poor mentorship might mean you’re not just unable to fight the zombie but are also forced to reanimate it.

It doesn’t help that research is a job that relies on zeal and curiosity, which are often fragile things. Intellectual zombies might not eat your brain but they eat away at your faith in the system.

Just discovered this really cool free application called Downlink that updates your desktop wallpaper with realtime imagery from a number of different geostationary satellites.

I just set my computer to the “Continental US” feed and now I’m able to see where I am (Indianapolis) from space in near-realtime. The future is cool!

The only downside to Downlink is that it appears to be Mac-only at the moment.

Sidenote: this reminded me of one of my favorite projects ever, Glittering.Blue by Charlie Lloyd. It’s not live, but it is still wonderful.

Photo by Elena Koycheva on Unsplash

Just in time for summer, a group of researchers published a preprint earlier this week showing that ancient Egyptians had domesticated sweet, red-fleshed watermelon by at least 3,560 years ago.

The team compared genomic data extracted from a leaf found in a mummy's sarcophagus to the DNA of all of the extant members of the genus Citrullus to get a more detailed picture about the watermelon's wild origin, which is surprisingly contentious. They also wondered whether the fruit was red-fleshed and sweet (which wild relatives of the watermelon are not).

They found that the DNA from the watermelon leaf from the sarcophagus had unique mutations in common with modern cultivars that are sweet and red-fleshed, and that the closest wild relative of these tasty varieties is a white-fleshed, non-bitter melon from southern Sudan.

And these findings fit with the archaeological record. There are even wall paintings depicting ancient Egyptians eating fruits that look very much like modern watermelons!

Many of us regularly consume chocolate, but may forget about the plant it comes from, Theobroma cacao, or cocoa. Cocoa can be grown in monocultures, which produce higher yields but are also more vulnerable to pest invasions and climate change. Alternatively, agroforests combine cocoa and shade trees; they may have lower initial cocoa yields but sustain higher levels of biodiversity and promote long-term ecosystem health and resilience.

When it comes to sustainability, smallholder cocoa cultivators in marginalized tropical regions are the ones making key land management decisions. Yet when deciding between cultivation options, cocoa farmers face frustrating trade-offs: should they prioritize short-term yield or long-term risk management and ecosystem health?

To study these factors, I traveled to Sulawesi, Indonesia, where some farmers address trade-off conundrums through a flexible approach, planting shade trees only in some parts of their cocoa fields. Their methods inspired a study which measured the influence of individual shade trees in cocoa farms. Individual shade trees improved soils in cocoa farms without necessarily decreasing cocoa yields. Our finding underscores the value of flexible cultivation approaches and could help cocoa farmers who want to transition towards more sustainable systems.

A genetic mutation gave this woman a pain-free life, a sunny disposition, and the ability to eat Scotch Bonnet peppers

Her novel genetics point the way to new targets for pain relief

Photo by Autumn Goodman on Unsplash

Imagine living your whole life without ever experiencing pain. Imagine having a permanently cheerful disposition, and no anxiety and fear. This is life for a 66 year old Scottish woman.

The woman carries a previously unknown genetic mutation that gives her consistently high levels of endocannabinoids, which are a kind of neurotransmitter similar to THC, one of the psychoactive compounds in marijuana.

The endocannabinoid system is involved in a whole host of bodily processes including pain, mood, and memory. The persistently elevated levels of endocannabinoids in this woman’s blood lead her to feel no pain and to have a consistently bright and positive outlook on life. When originally discovered, anandamide, the particular endocannabinoid this woman carries extras of, was named after the Sanskrit word for bliss. Her lack of pain phenotype is so strong that she can eat Scotch Bonnet chili peppers and only reports a “pleasant glow in her mouth” and enjoys the feeling of pulling stinging nettles from the ground with her bare hands during gardening. Throughout her life has undergone numerous painful operations without ever needing pain relievers.

Although the ability to feel pain is crucial to protect us from harm, reports like these are of great value as they offer new targets for development of pain relievers. Targets such as the endocannabinoid system are particularly desirable as they have the potential to treat not only pain but also mood disorders such as anxiety which is often present in many chronic pain conditions.

Earth is surrounded by minor planets — look no further than the Asteroid Belt

New Horizons had eyes for Pluto and MU69, but Mariakirch is much closer to home

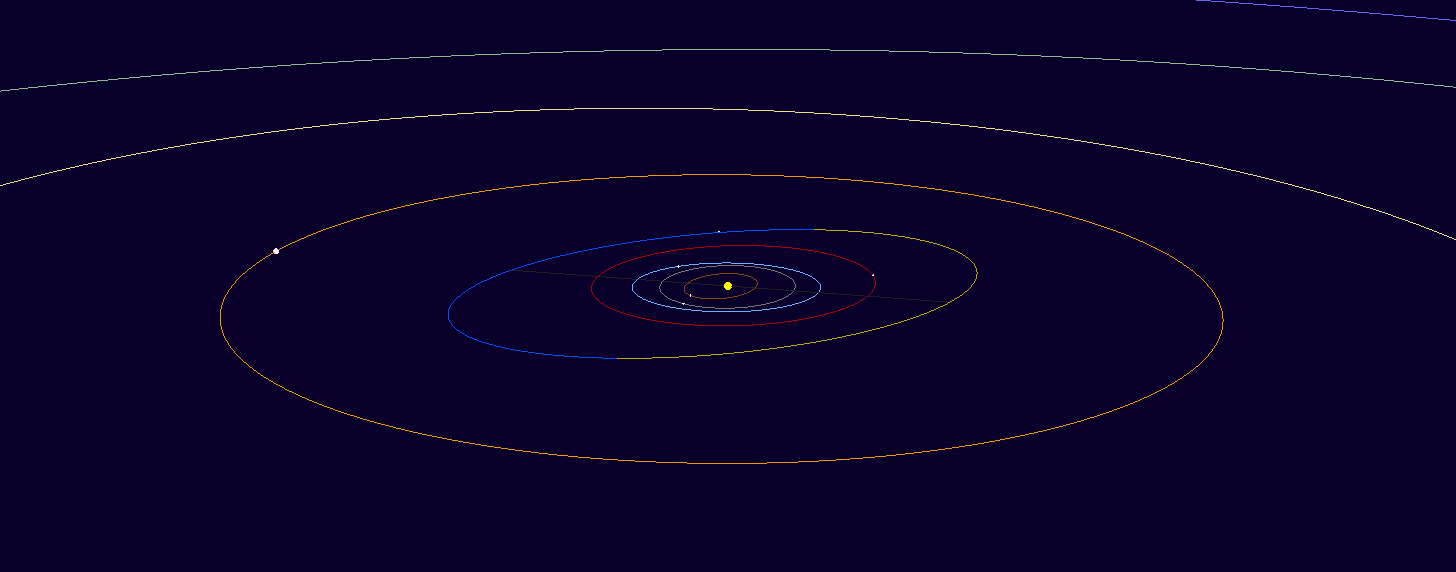

In the article on the life of astronomer Maria Winkelmann-Kirch I included an image of the orbit of a minor planet that is named after her.

The orbit of the minor planet Mariakirch. The half blue, half yellow circle is Mariakirch. It lies between the orbits of Jupiter (orange circle) and Mars (red circle).

The Minor Planet Center (MPC)

Minor planets are large asteroids orbiting the Sun somewhere between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter. They come in various sizes and we've identified thousands of the biggest ones using telescopes on the ground. There is actually one object in this region large enough to be considered dwarf planet: Ceres. We recently sent the Dawn probe to take some images. Sadly, Mariakirch probably won't get its own probe. It's one of the millions of minor planets, orbiting in the void between Mars and Jupiter.

Mariakirch was discovered at the Palomar Observatory on September 24, 1960 during a collaborative minor planet survey involving the Palomar Observatory and the Dutch Leiden Observatory. It is 2.8 AU from the Sun and takes 4.7 years to make a full orbit. For reference, Mars is 1.5 AU from the Sun and Jupiter is 5 AU.

You can learn more about all the minor planets in our solar system by visiting the International Astronomical Union’s Minor Planet Center. It’s where I got the image for the orbit of Mariakirch. As incentive, check out this cool gif of all the known asteroids moving around the asteroid belt.

International Astronomical Union Minor Planet Center

70 years ago, physicians used a heart defect to fix blue babies

The Blalock-Taussig shunt solves one congenital heart disease by recreating a second one

I recently met a patient who was born with a heart abnormality called Tetralogy of Fallot. Because it results in limited blood flow through the lungs, we call it a ‘cyanotic’ defect for the blue skin tone of a poorly-oxygenated baby. Congenital heart diseases are the most common birth defects; among cyanotic heart defects, Tetralogy of Fallot occurs most frequently.

Our primary intervention for repairing a cyanotic heart defect was originally developed in the early 1940s by two physicians at Johns Hopkins University. Helen Taussig, a cardiologist, noticed that certain “blue babies” (like those with Tetralogy of Fallot) had improved survival rates if they were born with a second heart defect.

This second defect was a ductus arteriosus, a small vessel that routes blood away from the lungs in a fetus. Before birth, the lungs are full of fluid and oxygen comes from Mom, so blood needs to be moved away from instead of towards the lungs. Usually, the ductus arteriosus closes around the time of delivery, but in some babies it remains open, allowing for more blood flow to the lungs after birth.

When Taussig realized that blue babies benefited from this additional heart defect, she consulted with Alfred Blalock, a vascular surgeon, to recreate it in cyanotic newborns. By 1945, they published on several successful surgical installations of what we now call the Blalock-Taussig shunt.

I’m especially fascinated by this story’s inspiration, with one defect rescuing another, so to speak. Finding protective factors within previously-identified problems is an outside-the-box (and apparently effective) approach.

As bizarre as it sounds, this same idea likely applies in many fields, scientific or otherwise: your answers might be hidden inside of your problems.

Photo by Josh Riemer on Unsplash

Did you ever think you would hear the term ‘implanted memory’ in an academic article rather than while watching a sci-fi movie? Well, this recent paper in Nature Neuroscience describing how scientists were able to create or “implant” an artificial memory into mice might blow your mind.

Scientists did this with optogenetics, which allows researchers to control neurons by shining light on them. Using this technique, they simultaneously activated an area of the brain related to the perception of an odor and areas of the brain associated with either reward or aversion. They were able to make mice respond to an odor they had never smelled before as if they had.

Implantation of false memories in mice had previously been achieved. In that study, scientists were able to alter a previous fear memory in mice by activating the cells that contained the memory. However, what's more exciting is that in the new study the researchers were able to actually “create” an artificial memory from scratch. This is the first time this has successfully been done without any external sensory experience, just by manipulating specific areas of the brain!

Researchers are now able to make mice "remember" something that never happened

Photo by freestocks.org on Unsplash

More surprisingly, the resulting artificial memory was quite similar to a real memory, as they both depended on the activity of the basolateral amygdala. But before you start questioning whether Inception is now possible, understand that this was done in mice. Memory systems in humans are considerably more complex, meaning that manipulating them might take more than just a little bit of activation.

We need a better spokesperson for the urgency of the climate crisis than Bill Nye

An angry comedian just isn't going to cut it

Eric Marshall on Wikimedia Commons

You may have seen Bill Nye's tirade against our collective inaction to prevent the worst impacts of climate change on HBO's Last Week Tonight with John Oliver. It reminded me of a story I heard recently about a time, not too long ago, when Bill Nye wasn't quite so furious at our inability to pass comprehensive legislation addressing climate change.

The year was 1996 and the place was Epcot, the Walt Disney World Resort theme park. The Universe of Energy, an Epcot pavilion sponsored by ExxonMobil since its opening day, debuted a new educational ride: Ellen's Energy Adventure.

On the ride, Bill Nye teaches Ellen DeGeneres where fossil fuels come from, while riders are transported into an animatronic jungle full of the dinosaurs whose carbonized remains we're burning every day. Then, the pair travel the country to explore how energy is created. While the ride recognizes the potential of solar, wind, and hydropower, Bill and Ellen still spend a lot of time exploring the benefits of fossil fuels. Jump to about the 20 minute mark to see for yourself.

ExxonMobil dropped its sponsorship of the pavilion in 2004. In 2017, the pavilion was closed (but not before its final show broke down and fans of the ride evacuated through the animatronic dinosaur land).

Adding this to the fact that he's not a scientist and his last attempt to save the world didn't really work out, I think we can find a better spokesperson for the urgency of the climate crisis than Bill Nye.

Did you know? The U.S. Congress has a committee on science, and anyone can watch their public hearings for free!

The U.S. House of Representatives has a committee on Science, Space, and Technology. The committee discusses issues relating to science research and brings their findings back to the rest of the House. It is currently chaired by Representative Eddie Bernice Johnson (D-TX), the first woman and African-American to chair the committee. You can read a great interview with Rep. Johnson on her vision for Congress' role in setting science policy here.

The committee's job is to connect the representatives of the American people to science research agencies, boosting the benefit of science research to the country. You can watch video of the hearings on the committee’s website. Or, if you are in the Washington DC area, you can also attend the hearings in person.

If you’ve ever wanted to learn more about how the federal government supports science research, these hearings are a great place to start. Past and upcoming hearings are all listed on the website and cover lots of topics including research budgets, new technology programs, and even diversity in STEM.

"NGC 5195 Galaxy - Hubble Space Telescope" by jwinfred on Flickr

The Hubble Space Telescope was launched into Earth's orbit in 1990. Since then, after a quick camera fix, it has taken some of the most spectacular images of our universe. With an unimpeded view of the cosmos, Hubble can peer farther and look deeper than any Earth-based telescope.

Last week, NASA and ESA released a wide-field view of our universe. To create this image, they stitched together over 7500 separate exposures taken over the past three decades. Astronomers picked a seemingly empty patch of sky and took multiple lengthy exposures with Hubble's camera. Then they stacked, or added up, the images to enhance the brightness of faint galaxies.

You are currently looking at about 265,000 galaxies in one astounding image

NASA, ESA, G. Illingworth and D. Magee (University of California, Santa Cruz), K. Whitaker (University of Connecticut), R. Bouwens (Leiden University), P. Oesch (University of Geneva,) and the Hubble Legacy Field team

Due to the vast distances we are dealing with and the finite speed of light, galaxies that are farther away are also from an earlier time. The particles of light we receive at our telescopes left these distant galaxies billions of years ago. The longer we keep the camera shutter open the more of these particles we can accumulate and the further back in time we can look. This image contains around 265,000 galaxies, the faintest of which are revealed by light they emitted over 13 billion years ago.

It's a really cool image to download and zoom into different areas. I recommend downloading the highest resolution PNG or TIFF image. Galaxies pop into view that weren't visible when you were zoomed out. There are galaxies of all shapes, sizes, and colors. It's a fun way to get lost in the cosmos.

See anything interesting in your zooms? Take a screen shot and send it to me on Twitter! We can talk about what you are seeing.

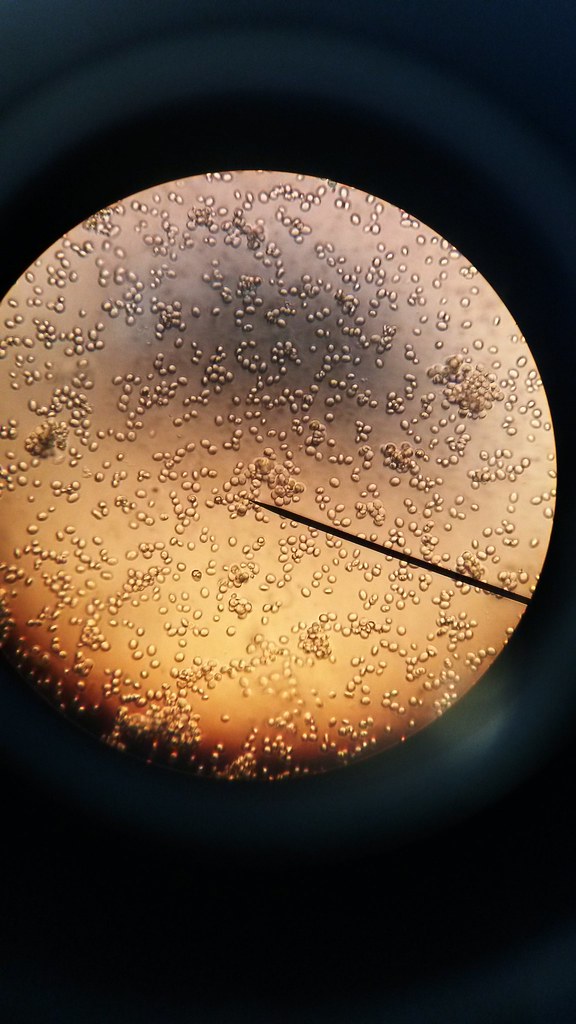

Yeast - the humble organism that makes your baked goods rise before you put them in the oven - has long been used as a "model organism" for all types of fundamental research in biology. But why?

The short answer is simply because it is so easy to manipulate for experiments. Many human cell lines take an average of 12 hours to replicate. Yeast colonies can double in just two hours. We can knock-out a gene and determine its effects in just a couple days. You can even directly replace many yeast genes with their human homologs (meaning, equivalent genes) and examine changes in the cells!

Yeast is an important model organism in biology that can help us learn about the human body

"Yeast Cells Under the Microscope" by BlueShift 12 on Flickr

I and other yeast researchers working on human and molecular genetics studies get a lot of scrutiny from people who think our work lacks clinical relevance. Any time we submit findings, we must know which human homologs are important, and how this could manifest into a disease in humans.

At the end of the day, yeast are remarkably similar to us. We should give these single-celled eukaryotes the love they deserve. If you're looking to read more about what its like to be a yeast researcher, check out this amazing piece by Dr. Laura Frontali as she reflects on her career.