Vlad Tchompalov on Unsplash

People trust scientists, says landmark survey, but there are troubling trends

Landmark Wellcome Global Monitor report surveyed over 140,000 people in 140 countries

Correction: an earlier version of this article mischaracterized The Story Collider; the sentence has been removed.

One in three people are skeptical of science. This has consequences, from parents hesitating to vaccinate their children, a rise in pseudoscience, to a persistent back-and-forth on climate change. According to the recent Wellcome Global Monitor (WGM) study, scientists, doctors and nurses enjoy a high level of trust globally, but half of the world knows little about science, and about one in five individuals feel excluded from the benefits of science.

Yesterday, the Wellcome Foundation published the WGM: the largest study to survey public attitudes towards science and health on a global scale. In collaboration with Gallup World Poll, the WGM study surveyed over 140,000 individuals, in 140 languages, living in over 140 countries. Wellcome studied the public's understanding of science, whether they trusted scientific individuals and institutions, what they believed was the impact of science in society, and their confidence in vaccinations.

Bill Oxford on Unsplash

The study reveals a high overall global trust (72%) in scientists and healthcare professionals, as well as vaccines (79%), but notes troubling trends, such as a loss in confidence in vaccine safety in higher income countries. Overall, the public's engagement with science is influenced by a combination of culture, context and background, suggesting that scientists need to keep this diversity of attitudes to science and health in mind when engaging with the public.

Below are key findings from the 132 page report.

Understanding science

Overall, around four in ten people reported having a lot or some knowledge about science. Perhaps unsurprisingly, it's younger people (aged 15-29) and those living in high-income countries who tended to rate their science knowledge more highly.

In nearly every region, when comparing across similar years of education, men were significantly more likely (49%) to say they knew some or a lot about science compared to women (38%). This gender gap was the greatest in Northern Europe (75% versus 58%), but was negligible with a difference of only 3-4% in three regions: the Middle East, South America and Southeast Asia.

WGM suggests that this gender gap may be due to social norms or a difference in levels of confidence between men and women. While the answer is unclear, one thing is certain: this gender gap affects who participates – and benefits – from science.

Luis Melendez on Unsplash.

To survey the level of trust the public has in scientists and healthcare professionals, WGM asked questions such as how much do you trust scientists in this country, and who do you trust most to give you medical advice?

Globally, a majority of people have medium (54%) or high (18%) trust in scientists, while one in seven people have a low level of trust. Various factors significantly influenced trust in scientists, including income, level of science education, area of residence (rural or urban), and their level of confidence in other societal institutions in their country (such as the government or military). Strangely, despite this being the largest study of its kind, 85% of the difference in how much people trust science is not explained by these factors. Something else is at play here. Regardless, it's interesting to note that the most important predictor of trust in scientists was whether the individual had learned science at school, followed by their level of confidence in national institutions.

As for science in society, 70% of people around the world feel that science benefits people like them, where Saudi Arabian citizens felt this sentiment most strongly (89%). Low trust in scientists was most common in Central Africa, Southern Africa and South America – and these regions were also among the ones least likely to believe that science benefits society, and felt excluded from the benefits of science.

Similarly, individuals have medium (43%) or high (41%) trust in doctors and nurses, while 13% have not much or no trust. There was no difference in confidence levels in hospitals across high and low-income countries, but across the world, those with lower household incomes were likely to have less confidence in healthcare systems. Interestingly, Rwandans are the most likely (97%) to express confidence in their healthcare system, which is a reflection of the recent improvements in the country, including a radical improvement in life expectancy.

Attitudes towards vaccines

So if the public (mostly) trusts scientists and healthcare professionals, then what's with the fuss around vaccinations?

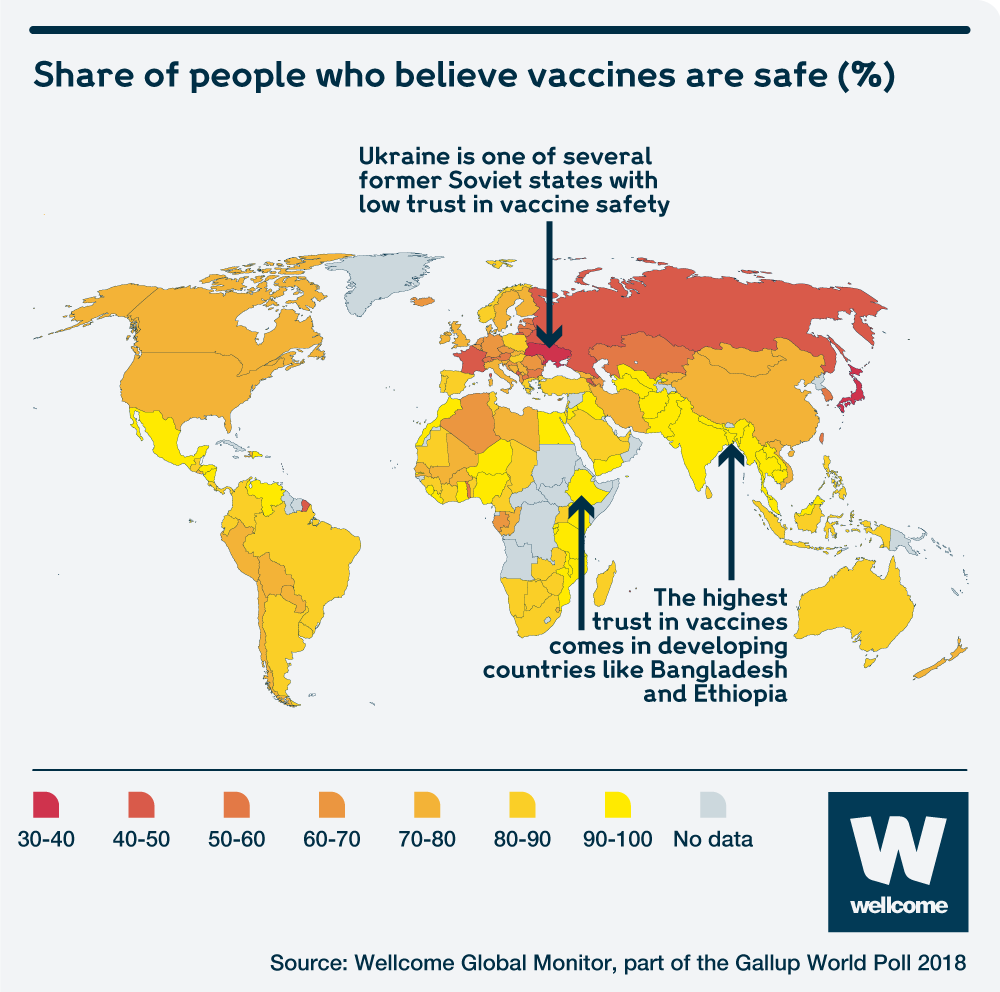

Globally, most people strongly (61%) or somewhat (18%) agreed that vaccines were safe, but people in high income countries were less likely to agree that vaccines were safe, especially in regions such as North America (72%) and Eastern Europe (50%). The situation is particularly dire in France, where one in three people disagree that vaccines are safe, which is the highest in the world.

If it's any consolation, not all individuals who are skeptical about vaccine safety deny the effectiveness of vaccine safety. For example, while only 50% of Eastern Europe believe that vaccines are safe, 65% agree that they are effective. While no clear relationship was found between levels of science education and vaccine confidence, people who trust doctors and nurses more than any other source of information were more likely (72-81%) to agree that vaccines are safe across the world.

In contrast, a majority of people in low-income countries agree that vaccines are safe, with South Asia reporting the highest proportion (95%) of trust. Notably, Rwanda and Bangladesh have high rates of agreement on vaccine safety, effectiveness and importance, and also have high success rates in immunization despite facing difficulties in implementation.

More than 90% of parents in this study say their children have been vaccinated - which is a relief - but if a mere 6% (i.e. >188 million individuals) do indeed remain unvaccinated, this poses a significant risk to herd immunity. It's findings like these which emphasize why the World Health Organization had to declare vaccine hesitancy as one of the top ten global threats in 2019.

Perhaps it's time for us to re-think how we approach public engagement. Scientists have launched numerous public outreach initiatives, ranging from blogs, podcasts to social media campaigns . It isn't a case of not enough outreach, but perhaps instead these initiatives exist in echo chambers and fail to reach individuals who need access to experts most. Yes, the public needs to understand science, but perhaps scientists, too, need to better understand the public and the factors influencing engagement – especially the diverse range of attitudes people all over the world have when it comes to science and health.

Interestingly, the WGM findings aren't entirely surprising. For example, earlier this year, 3M released their annual State of Science Index, where a survey of 14,000 globally revealed that scientists as seen as credible but not approachable, and that one in three people (35%) are skeptical about science. What makes the WGM different is the sheer global scale of the study – these findings can act as a baseline as public engagement initiatives attempt to address science literacy, public trust in scientists and boost vaccine confidence.

Christin Hume on Unsplash.

Jayshree Seth, who is a corporate scientist and the chief science advocate at 3M, was surprised by the complexity of how people view science. "[The public] see [science's] benefits when it comes to our macro world and serving the needs of larger society, but when it comes to their own individual lives, they are less likely to see the impact and benefits," she says, and points out that there is still more work to do to advocate for science.

So how do we move forward from here?

Seth says that results from global science surveys, like the WGM and the 3M State of Science Index, can help open up candid two-way conversations. "We often discuss why it matters what people think of science," says Seth. "The overwhelming conclusion is that it matters because the future of science and the contributions science makes to society depends on the public being favorable to science. Everyone has long agreed that there are potential consequences if people don’t see the importance of science in their lives, because those attitudes could eventually undermine the pipeline of innovation."