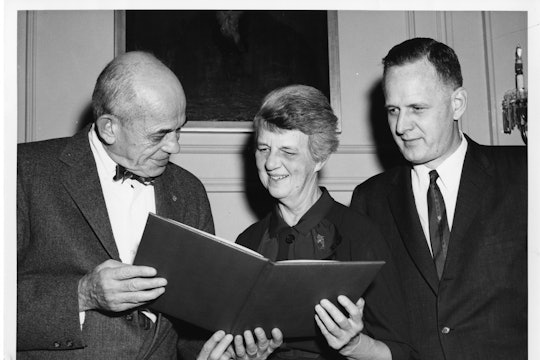

Alan Richards, Smithsonian Institute ( SIA-SIA2008-5069)

Meet Rebecca Lancefield, the revolutionary microbiologist whose work paved the way for antibiotics

The sage of Streptococcus wouldn't take "you don't belong here" for an answer

Streptococcus is not the kind of bacteria that you mess around with. They’re notorious for causing illnesses as varied as strep throat, pneumonia, scarlet fever, and flesh-eating bacterial infections. Renowned 20th century microbiologist Rebecca Lancefield, however, loved Streptococci. So much so that she dedicated her 60-year scientific career to sorting them into different categories. It was her work with Streptococcus and other bacteria that ultimately helped pave the way for antibiotics and an understanding of how and where infections happen.

Lancefield was born in 1895 in Fort Wadsworth, a military installation on Staten Island, New York. Her father was an army officer, which led to a rather nomadic early life and schooling. However, her mother strongly believed in education for women, and educated Lancefield and her five sisters. This educational foundation led Lancefield to Wellesley College in Massachusetts. She was originally a French and English major, but became deeply intrigued by her roommate’s work in zoology, and switched her field of study, graduating with a zoology degree in 1916.

Lancefield wanted to continue to graduate school after Wellesley, but couldn’t manage it financially. Her father had died while she was in college, and her mother needed money. So, Lancefield worked for a year as a teacher, and subsequently earned a scholarship that enabled her to work in a lab at Columbia University in Manhattan while earning her master’s degree. It was at Columbia where she first began working with bacteria.

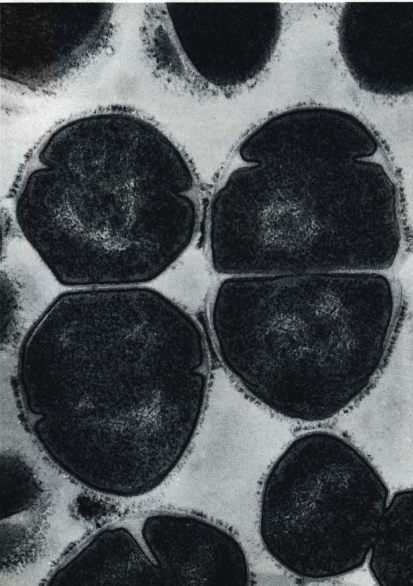

Streptococcus seen under 70,000-fold magnification with an electron micrograph

Rockefeller University

Lancefield’s love for bacteria began with strains other than Streptococcus. As a master’s student, she researched Staphylococcus, the bacterial culprit behind staph infections, highly contagious infections that are often easily treatable but can be dangerous if they reach deeper tissues. After graduating in 1918, she joined the lab of molecular biologists Oswald Avery and Alphonse Dochez as a technician. Avery and Dochez had built their careers on pneumococcus (which causes pneumonia), and had just been tasked by the Surgeon General of the Army to investigate the cause of streptococcal infections in U.S. troops in Texas.

At the time, it was unknown whether it was just one or many strains of Streptococcus that could cause problematic infections. After collecting samples from the soldiers, Lancefield, Avery, and Dochez identified 125 different strains, most of which they were able to sort into four distinct groups. They published their results in a lengthy 34-page paper in the Journal of Experimental Medicine. It was quite uncommon for a technician to earn authorship on a paper at that time, but Lancefield had been an integral part of the team, and earned her spot.

With the work in Texas complete, Lancefield returned to Columbia as a research assistant while her husband, who was also a scientist, finished his PhD. They both accepted teaching positions at the University of Oregon and moved there for a year. In 1922, they returned to New York, where her husband joined the zoology faculty at Columbia, and Lancefield began her PhD in the university's immunology and bacteriology program.

Rebecca Lancefield and her husband Donald, 1928

Rockefeller University

Lancefield had hoped to work with bacteriologist H. Zinsser at Columbia, but he wouldn’t let her work in the lab because she was a woman. So, she did the bulk of her research with biologist Homer Swift at Rockefeller University. Studying for her PhD at Columbia and doing lab work at Rockefeller at the same time was often, quite literally, a balancing act, as she had to carry her test tubes between campuses. It’s an image I’m fond of: aspiring microbiologist Rebecca Lancefield, with a rack of Streptococci samples jostling on her lap, traveling back and forth between the west to east sides of Manhattan.

Lancefield’s doctoral work was foundational for our understanding of rheumatic fever, an inflammatory disease. At the time, scientists thought that a specific group of Streptococci, the viridans, were responsible for rheumatic fever. Lancefield's doctoral work conclusively demonstrated that they were not the culprit.

Lancefield received her PhD from Columbia in 1925, and continued her work at Rockefeller, investigating Streptococci’s molecular machinery. By studying the reactions between different strains of Streptococci and different types of antibodies, Lancefield was able to determine the antigens that different types of Streptococci have, and therefore what kind of cells each strain could infect.

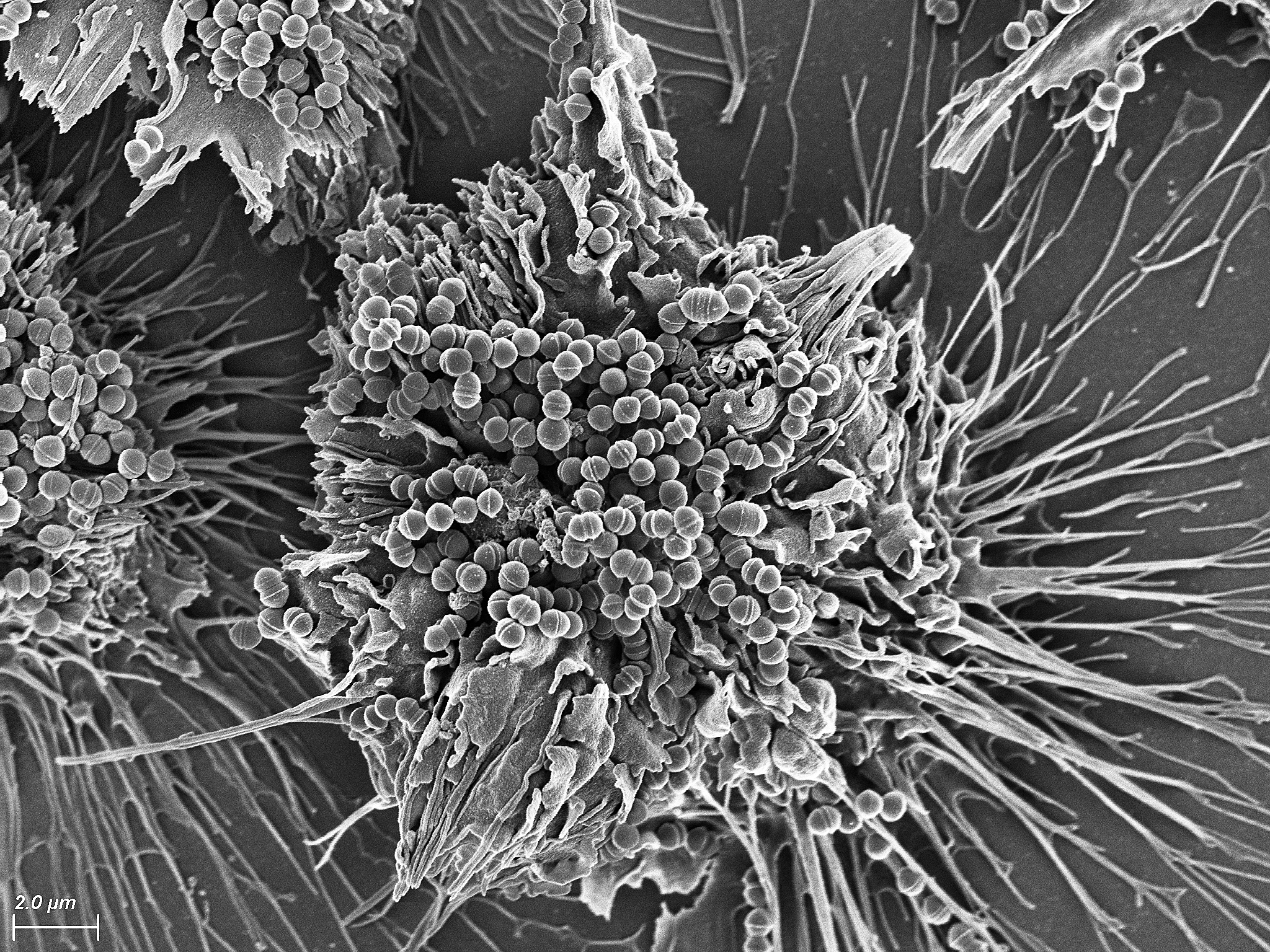

A modern electron micrograph of streptococcus bacteria.

NIH via Rockefeller University

The establishment of a Streptococci pecking order was necessary not only for basic science, but also for our ability to do epidemiological studies on diseases caused by these bacteria. Scientists originally believed that different strains of Streptococci caused different diseases, but Lancefield’s research showed that some strains could cause a variety of symptoms.

At Rockefeller, Lancefield was known as “Mrs. L.” She was meticulous and deeply dedicated to her science, so much so that she was reluctant to leave the bench to actually write up her findings, and was totally uninterested in administrative work.

Lancefield was also a kind colleague and dedicated mentor. Marjorie McCarty, a scientist in the lab, once asked to leave at 3 pm because her son was sick. Lancefield responded flustered and embarrassed that someone would even need to ask to leave. According to Lancefield's close collaborator, Maclyn McCarty, "A visitor with an interest in streptococcal problems would leave with a thorough indoctrination and with most of his questions answered — as well as with a collection of cultures of reference streptococcal strains and samples of the relevant antisera [blood serum with antibodies]."

Lancefield worked in the lab into her 80s, often staying the night, and continuing to work the next day. She also made a killer eggnog, a recipe that still today is shared widely within scientific circles. After 86 years and countless contributions to our understanding of bacteria, Lancefield passed away in 1981. But her bacterial strains live on. You can visit the 6,000 or so strains that she collected over her lifetime at Rockefeller University — descendants of bacteria that spent many long rides on the lap of one of microbiology’s most dedicated and inspiring women.

Lancefield in the lab

Rockefeller University