Stephen Atkinson

Polar bear numbers are rising in a once too-frigid Arctic basin

Thick Arctic ice is melting into conditions better suited to life. But the region's warming is trending towards trouble

In 1881, the tall ship Proteus carried the Lady Franklin Expedition through the Nares Strait, the northernmost extent of the shallow stretch of water between Arctic Canada and Greenland.

They were establishing a meteorological station as part of the First International Polar Year. What they did not know as they disembarked in what would become known as Lady Franklin Bay, was that their relatively ice-free passage resulted from an unseasonably warm year. All attempts at resupply over the next two years would fail. Only six men would survive. As the Proteus returned south that first summer, ice closed the path behind it.

More than 130 years later, above the same Kane Basin water where the Proteus had passed, Peter Hegelund — Program Coordinator for the Greenland Institute of Natural Resources — leaned out the side of a helicopter, his rifle pointing out across the frozen, flat sea. Through the sight, he watched a white bear racing toward the open water in the distance. A former policeman and avid hunter, he — more than most — understood the importance of a good understanding between shooter and pilot. He waited for the pilot’s signal, and then holding his breath, he fired. The dart bounced off the bear’s rump, the long orange tail of the dart still visible, fluttering in the deep snow where it had landed. As Hegelund lowered his weapon, the helicopter circled back to retrieve the sample embedded in the dart’s tip: hair and skin carrying precious genetic material that would be sent to a lab to identify the bear now disappearing on the horizon.

.png)

“It was a strange feeling,” said Hegelund, “We could see Greenland and when we turned the helicopter the other way around we could see Nunavut.”

Surveys like this one have been carried out on many of the 19 polar bear subpopulations spread across Arctic Canada and the US, Greenland, Svalbard, and Russia. But unlike most, the results would reveal something different about the Kane Basin bears — the smallest and most northerly of polar bear populations. Unlike most polar bear populations, which were showing a drastic decline, the Kane Basin bear population was actually increasing.

Back in the 1990s, scientists from Greenland and Canada began documenting the population size and health of the Kane Basin polar bears. Using a "capture-recapture" method, the scientists tranquilized bears by shooting them from a helicopter and then marking them with ear tags or tattoos. In subsequent years, scientists used the ratio of how many marked bears were recaptured to estimate population numbers. At that time, the focus was on the bears, with little consideration given to the condition of the sea ice on which they lived.

“It was pre-climate change effects on polar bears,” says Kristin Laidre of the University of Washington and the Greenland Institute of Natural Resources, lead author of a study of the Kane Basin bears recently published in Global Change Biology.

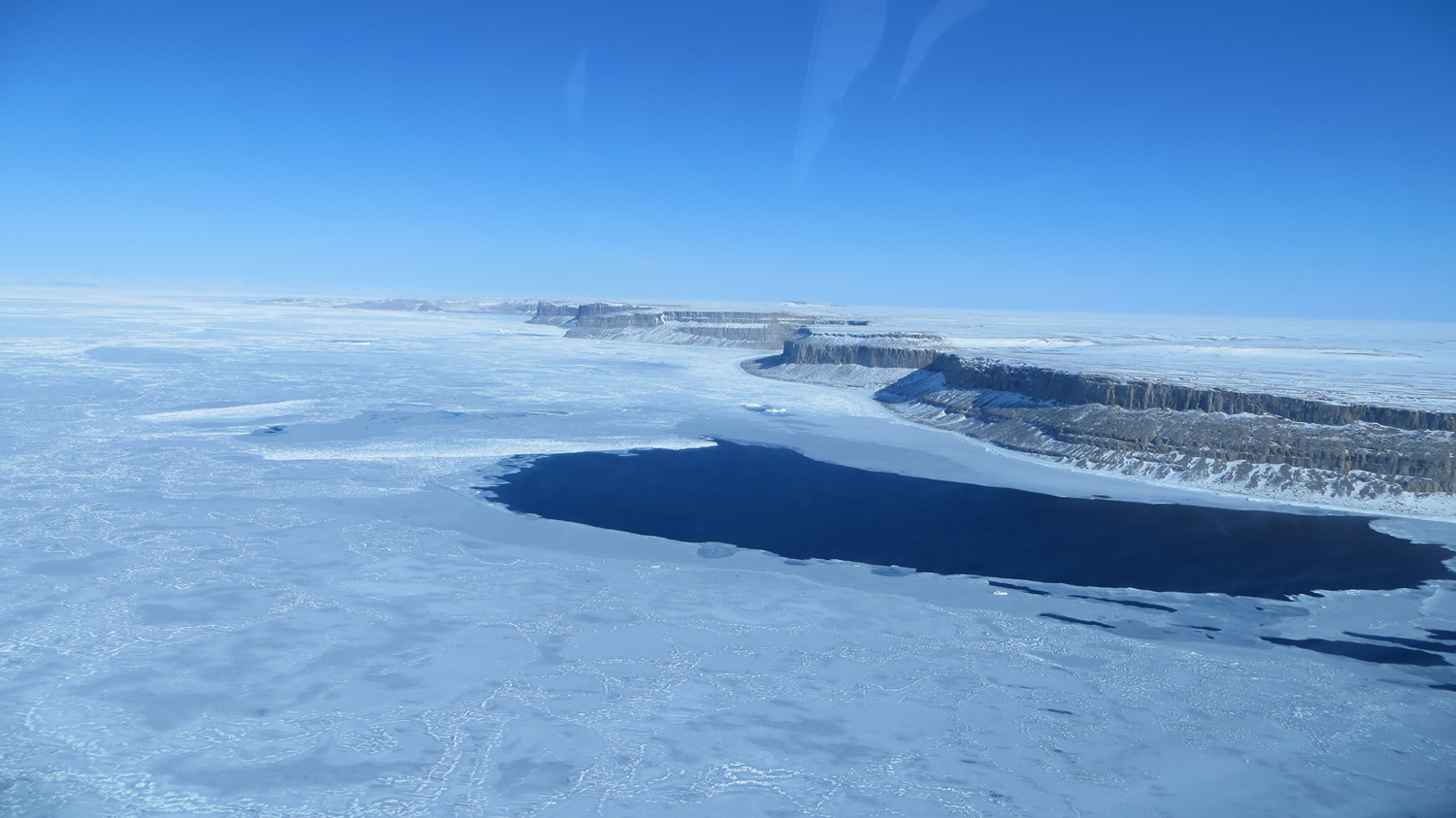

Kane Basin. This rapidly shrinking world is seen as a climate refuge for ice-dependent species like the polar bear.

Stephen Atkinson

Recent surveys reported in that study were initiated in the wake of a 2010 memorandum of understanding between the governments of Canada and Greenland on joint management of polar bear populations. Laidre was one of five scientists assigned to a scientific working group to advise the joint commission on polar bear management. This time, the team was well aware of the debilitating impacts of climate change on polar bear populations. So the focus of the planned surveys, from 2012 to 2016, would not just be on the bears, but also on the ice.

Polar bears depend on sea ice. Classified as marine mammals because of the time they spend at sea, polar bears rely on sea ice to travel, hunt, and breed. Most polar bears live in areas with annual sea ice — ice that melts and reforms each year. But year after year, summer sea ice has thinned and reduced, leaving some polar bear populations with only open water, subjecting the bears to enforced land-based fasting over the summer months and limited access to prey — seals, which live in the open sea and can only be reached from the ice. The results for most polar bears populations have been dramatic, with drastic declines predicted by the end of the century.

Realizing they needed to understand the interaction of the bears with their rapidly changing habitat, Harry Stern from the Polar Science Center, also at the University of Washington, used satellite imagery spanning the more than twenty years between the two bear surveys to observe changes in the summer ice conditions. What he found was no less dramatic in the Kane Basin than the changes further south, but with one key difference.

Polar bear

Carsten Egevang

Historically, the Kane Basin had been dominated by multi-year sea ice — thick ice that lasts multiple years — rather than annual ice that had dominated more southerly polar bear habitats. In fact, the Kane Basin sits on the southern margin of what is wistfully known as "The Last Ice Area", a region of shallow seas and islands along the North American margin of the Arctic Ocean and the only place in the Arctic where thick multiyear ice — which once dominated these waters — still exists. This rapidly shrinking world is seen as a climate refuge for ice-dependent species like the polar bear.

Stern’s comparison of the satellite imagery showed that in the 1990s, half of the sea ice in the Kane Basin was multi-year ice — the other half melting and reforming over the summer months. But in the 2010s, almost all of the sea ice (95 percent) had become annual ice, leaving only a tiny proportion of thicker multi-year ice. Where once this thick ice could not be penetrated by the 24-hour summer sunlight, leaving the waters beneath low in activity, the now thinner annual ice brought light to these once dark waters, promoting algal growth. The algae attracted fish and the fish brought seals, the main diet of polar bears. Before, the Kane Basin bears had struggled to eke out an existence in an Arctic desert, but now the transition from multi-year to annual sea ice gave them easier access to prey.

Compared with the 1990s, the bear population had grown from 224 to 357 bears. The bears were fatter and had increased their range. They were also showing stable reproduction. The shift to annual sea ice clearly correlated with improved outcomes for the bears. In contrast to their southern cousins, stranded and hungry on land, climate change had brought the Kane Basin bears a windfall, but one that is likely to be short-lived.

Kane Basin may become one of the final havens for polar bears and other ice-dependent species

Stephen Atkinson

“Under unmitigated climate change, meaning there are no changes to policies, the sea ice will continue to thin, and at some point, it will not be good for bears there,” said Laidre.

Without a drastic reduction in carbon emissions that can slow ice loss, the trajectory of rapid environmental change in the Kane Basin is the same as further south: a future of complete summer ice loss in which the bears can no longer reach their prey. Even the prospect of moving to colder waters further north yields little hope, as the deep Arctic Ocean has far less capacity for increased primary production compared with the fertile shallow waters of the Kane Basin.

As we lurch toward an unknown future where the climate continues to warm and sea ice is progressively lost, the Kane Basin may become one of the final havens for polar bears and other ice-dependent species. But unlike the men of the Lady Franklin Expedition, whose fate was sealed in the Kane Basin all those years ago by ice closing in from the south behind them, the bears’ fate may be sealed by a dark southern horizon of encroaching open water.