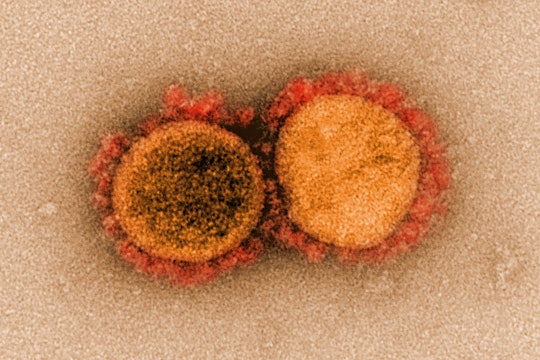

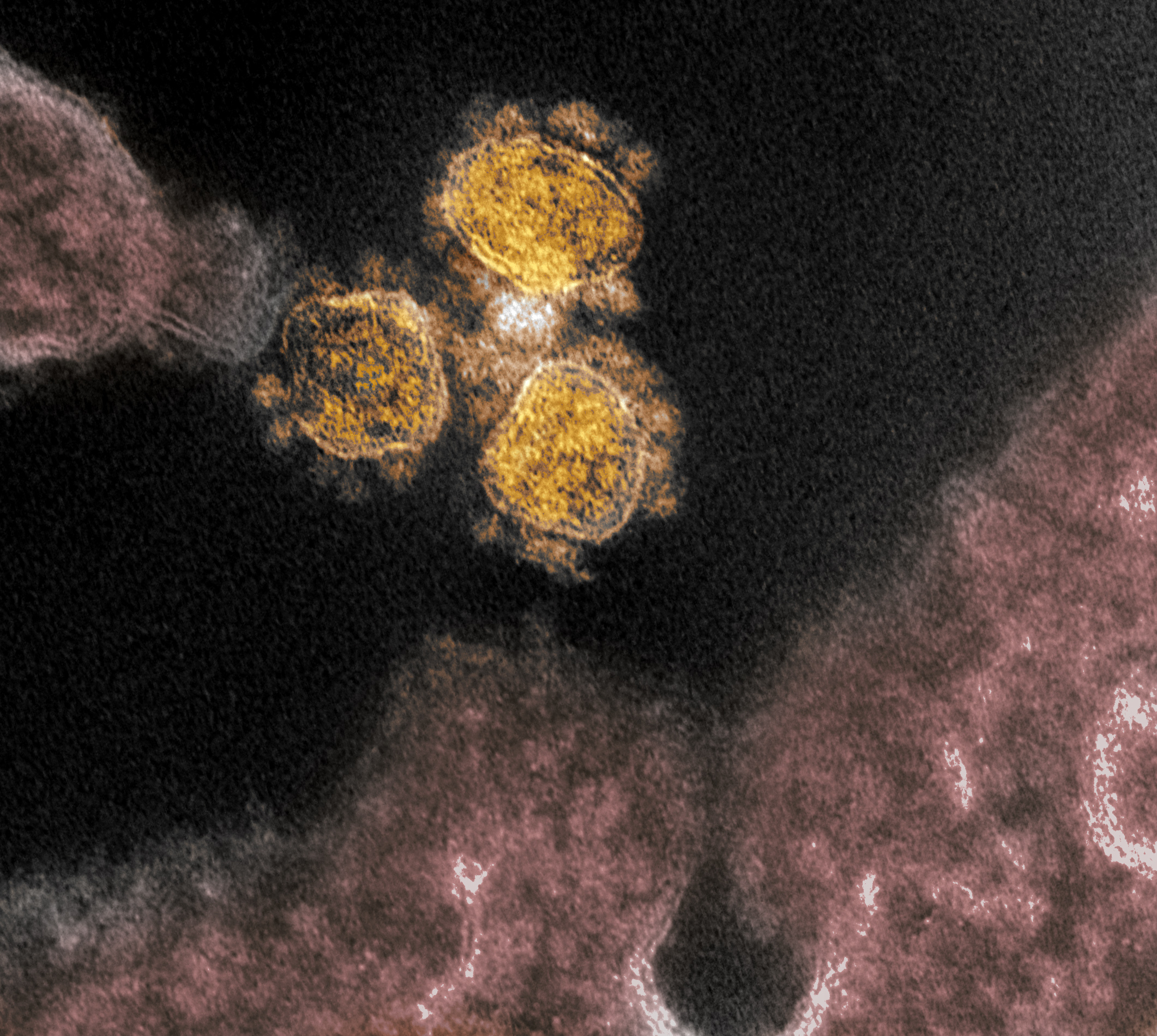

National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIH

No one really knows if coronavirus is going away in the summer

Which is all the more reason to continue strengthening policy and public health responses

Spring 2020 is already The Lost Season. Everything from major sports events to local elections have been put on ice by coronavirus. SARS-CoV-2 spread from its first leap into a human in China to an international pandemic in only a few months. Epidemiologists around the world have been collaborating to figure out what the possible futures for this pandemic might look like: when will it go away? When will it be safe for us to start figuring out what comes next? Part of this process has been asking a question: some viral illnesses, like the common cold, seem to ebb in the summer time – so what does this mean for SARS-CoV-2? Could Summer 2020 look different than the spring? Will coronavirus return in the fall?

And the answer is that it’s complicated.

COVID-19 is believed to be spread primarily through droplet transmission. This means that an infected and contagious person has cough, sneezed, even maybe talked nearby and has expelled droplets containing virus that could come directly into contact with another person. Alternatively, the virus can spread via surfaces the infected person has interacted with. Other respiratory illnesses like the flu and coronaviruses in the same family as SARS-CoV-2 are spread in a similar way. We have laboratory evidence corroborated by epidemiological data that some viruses transmit best in cooler, drier weather. The dryness lets droplets linger in the air longer, because there is less water vapor for them to encounter. Just like smaller drops of water dangling on a faucet can fight against gravity until one too many joins up and the whole thing falls, virus droplets linger until they run into one too many other liquid droplets in the air, and they are forced to settle.

It’s reasonable to ask if this new coronavirus will behave the same way. One group looked at this question by comparing the infection rate of 100 Chinese cities, and found that, like you might expect from the flu, cities with higher temperature and higher relative humidity saw a statistically significant decrease in the R0 (pronounced "R-naught," the average number of people infected by a single person) of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. A second group did a similar analysis, expanding their data set to encompass the entire globe, and found preliminary evidence of a similar pattern emerging: areas with more extensive community spread were found along a particular latitude corridor with relatively cooler temperatures and lower humidities. This sweep of the Northern Hemisphere includes geographic areas encompassing the epicenters of the outbreak, from China and Southeast Asia, to the Middle East and most of Europe, to the continental United States. So there is some reason to believe the spread of SARS-CoV-2 might abate a little in the summer months.

But would it be enough to change the trajectory of the curves we are currently on, or to change policy prescriptions as we come into the warmer months in the Northern Hemisphere?

Coronavirus particles (round gold objects) are shown emerging from the surface of cells cultured in the lab.

To answer this, we can look at places like Singapore, Hong Kong, places lying on the Equator, and countries in the midst of their summers in the Southern Hemisphere. All of these places appear just as capable of sustaining local transmission as anywhere else, despite the weather being relatively hot and humid. Many of these countries, especially in Southeast Asia, did largely control the first wave of their epidemics – but this was due to their effective policy interventions, not their climate. If we can draw any lessons from their experience, it is that early physical distancing measures and aggressive testing-and-tracking of new infections are key for controlling the spread of the virus – not that the summer alone will bring us any reprieve.

When a virus is new, like the virus causing COVID-19, it likely won’t follow a typical seasonal pattern until it “settles in” or “burns out." This virus has a temporary advantage: our immune systems have never seen it before. It can spread more easily than other viruses that have been coexisting with humans for a longer time. These older viruses have to compete against a certain level of herd immunity within the population, and often can only spread when conditions are more to their advantage, like in the cooler, drier air of the winter. But for the time being, SARS-CoV-2, rather than competing with our immune systems, is only competing with our public health interventions, and the speed of our science. These will be the keys to outwitting the virus in its first year of spread, rather than the likely eventual evolution of a seasonal pattern more similar to other respiratory viruses.

Since SARS-CoV-2 likely won't be fading away over the summer, what does that mean for the fall? A lot of that depends on how well we can time our public health interventions. The virus may have a slight advantage in transmitting itself as the weather begins to turn, but a much bigger factor will be how prepared we are to deal with a likely resurgence after stemming the initial phase of the epidemic. Places like Singapore and Hong Kong are seeing this second spike of infections when they began loosening social distancing policies. After imported cases brought in by foreign travelers and workers, as well as an increase in unlinked local cases (where no source of the infection could be found), they have begun a second round of closing down – from temporarily re-closing schools to mandatory two week quarantines for non-nationals to new limits on immigration. The same will likely be true everywhere, and as we consider things like whether schools will reopen in the fall, or if sports can resume with fans – we should expect a second wave of cases to occur. But we also have to have a new battery of tools to stem the tide of SARS-CoV-2 on the second-go-round.

So will summer and fall 2020 be a repeat of the spring? That depends on us. On the efficacy of our public policy, how well we can use science to guide our next steps, and how quickly we can ramp up our scientific interventions to give us an advantage over a virus we must work together to understand.