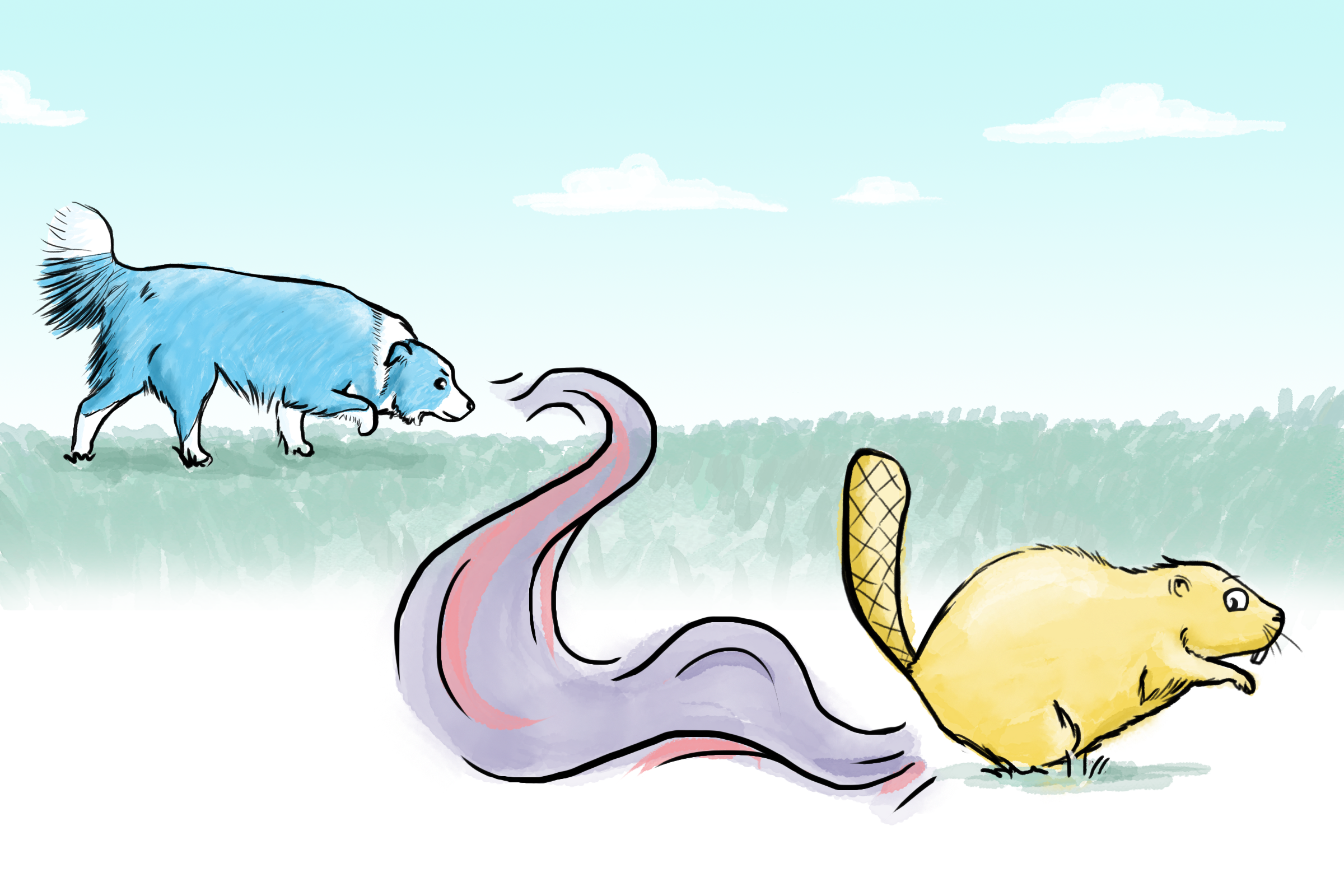

Conservation dogs can track individual beavers by the scent of their anal secretions

The dogs' accuracy in telling animals apart using information-packed anal scents will help wildlife management

Ed: Welcome to Butt Month. Every Tuesday in September, Massive will publish an article on the evolution, science, and technology surrounding the butt. If it touches the butt, we'll be covering it. Why Butt Month? Why not.

Conservation dogs have been trained to locate animals both dead and alive. Given that dogs' sense of smell is approximately 10,000 to 100,000 stronger than ours, they are excellent partners for tracking animals in the wild.

With the help of three "scent detection dogs" named Tapas, Chilli, and Shib, researchers have shown that with persistent training, this olfactory advantage could dramatically improve conservation canine handlers' work. How? By improving upon their ability to identify animals by tracking their individual butts.

The story of "conservation dogs" goes back in the 1890s, after one of New Zealand's first-ever recognized conservationists, Richard Treacy Henry, trained a few pups to assist in the relocation efforts of two flightless birds, the kiwi, or tokoeka and the kakapo. Though conservation dogs detect animals using many kinds of scents and excretions, recently, these identifying substances have become increasingly butt-focused.

No other bodily secretions had been shown to provide the same level of identifying information that scat does. That is until Frank Rosell, David Kniha, and Milan Haviar looked into the matter, in work published in BioOne Complete. The research team at the University of South-Eastern Norway tested the dogs on something new: the anal gland secretions (AGS) of the Eurasian beaver.

The Eurasian beaver once spanned nearly the entire Eurasian continent. At the start of the 20th century, however, their populations were down to approximately 1200 individuals. Fortunately, they've since been reintroduced throughout Europe, and now are recognized by the IUCN as "Least Concern" with 1.04 million animals and counting. Still, they are a keystone species that requires regular monitoring and protection.

Since these beavers communicate primarily through scents, they've invested quite a bit of evolutionary development into their anal glands. In fact, the anal glands are not the only butt-local organ that beavers use to make themselves known to their neighbors. They use two, each of which is located between the base of the tail and the pelvis: castor sacs, which produce a brown mucous called "castoreum," and anal glads, the "true" glands which produce AGS. AGS is a "thick gray paste" in female butts and a "yellowish oily fluid" in males. AGS contains a great deal of information about an individual beaver, including species and subspecies, sex, identity, kinship/family role, age, and social status.

Outstanding Scent Detection Using Beaver Butt Juice

The team collected 75 AGS samples from live-trapped beavers. To extract the samples, the scientists needed to manually induce the beaver’s expulsion of AGS.

Eurasian beavers excrete both castoreum and AGS on small mounds of mud on riverbanks. These locations mark their territory and are easily detectable by neighboring visitors and human researchers alike. Still, these samples could not simply be collected from the mounds, since Tapas, Chilli, and Shib needed to train with the pure fluids.

The first step was to empty the animal’s rectum to clear out any odors that would distract the dogs from the AGS. Next, the team rinsed each beaver's cloaca – an extra step to ensure the bottom was free of non-AGS particles. Finally, through manual control of the papillae, the team safely removed the AGS for training and testing.

Tapas, the conservation dog

Courtesy of Frank Rosell

Tapas, Chilli, and Shib were presented with a lineup of AGS samples, accompanied by distraction scents (these were either a blank vial, coffee grounds, tobacco, or herbal tea), and were expected to identify the target among the blank or other scents. The pups first smelled the focal AGS on its own when given the command, “Smell!” After memorizing the scent, they would then go select the match in the lineup with the command, “Search!” The lineup held both the target and the distractions.

Finally, upon finding the target, Tapas, Chilli, and Shib would lie down and point to the sample with their nose or paw.

After the 9-month training period was complete, the dogs’ sniffers – and the identifying potential of AGS – were put to the test: Six vials in total were lined up, including four AGS samples, one distraction scent, and one blank. Tapas, Chilli, and Shib were each subjected to ten trials. The results were stunning. Each dog showed themselves to be beyond capable of finding the precise beaver by their anal excretions alone.

Their successes were measured in a few ways: sensitivity (the number of times the dog correctly identified the target anal gland), specificity (how often the dog correctly indicated a distraction), and accuracy (the collective term for both sensitivity and specificity). Overall, Tapas, Chilli, and Shib scored an 88.9% accuracy, 66.7% sensitivity, and 93.3% specificity.

Chili, the conservation dog

Courtesy of Frank Rosell

Not only are these findings a clear demonstration of scent detection dogs’ ability to extract highly specific information from AGS, but it also points to the incredible reliability of the Eurasian beaver’s hind-centric olfactory communication system.

How AGS Scent-Matching May Change K9 Conservation

Although this is a remarkable discovery, it does have some shortcomings. First, the study had a small sample size, given that there were only three dogs tested. Secondly, as acknowledged in the publication, the researchers did not conduct a test where the target AGS was not present. This could have misrepresented the error rate of the dogs since the focal beaver might not always be present in the search area.

Aimee Hurt, Co-founder and Director of Special Projects for Working Dogs for Conservation (WD4C), recognizes the necessity of both DNA analysis and individual-specific scent detection in dog-assisted conservation work. Hurt said via email: "Dogs matching individuals by scent in the conservation realm has been reported in scientific literature a few times since 2007, and yet the go-to tool remains sending samples to the lab for DNA analysis. This is most commonly how our teams work, where dogs are trained to find as many samples as possible from a given species, and then the lab determines which animal the sample comes from if that's a relevant question for the objectives of that study.”

This hyper-specific identification ability presents a promising advantage in K9 conservation work. For instance, one common problem in monitoring efforts is lost or malfunctioning tracking devices. If wildlife managers needed to track a specific individual, scent detection dogs could temporarily replace the faulty equipment. Also, many species are highly sensitive to standard practices like live-trapping. A hands-off monitoring approach using dog-assisted scent tracking could relieve some of this pressure.

When asked about the circumstances in which conservation dogs would need to perform scent-matching in this way, Hurt explained that “individual identification is only one example of the ways we can capitalize on dogs' ability to discriminate scents and put that ability into indoor, controlled, lab-like settings.”

According to Kniha, "Identifying a specific animal is technically being done by detection dogs whenever they search for a specific animal. Identifying specific species or subspecies can be very useful for...distinguishing species that are very difficult to tell apart." His hopes for future application of this work are high. "I sure hope it will inspire more people to explore the potential abilities of dogs, which I believe are much greater than what we already know."

Canine conservation work has approached a new horizon. Building off past discoveries of dogs’ ability to scent-match individuals based on scat samples, Rosell and his fellow researchers, along with the awe-inspiring Tapas, Chilli, and Shib, have demonstrated that a wealth of highly valuable information is stored in the butts of Eurasian beavers. The extent to which this information can be used relies on the sniffer's power and the availability of anal secretions.