NOAA

Climate change is causing floods all over the world. Here's what you can do to help

People are dying in Mozambique and Zimbabwe, in Nebraska and the Dakotas. And millions more are at risk.

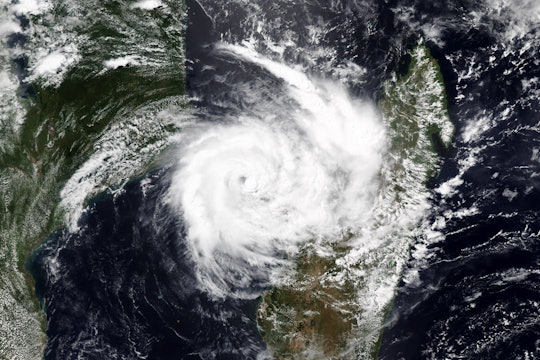

Ten days after Cyclone Idai, hundreds of people have been reported dead, and over a hundred thousand people have been displaced in Mozambique, Zimbabwe, and Malawi. Simultaneously, catastrophic floods have covered the Midwest of the United States: floods in Nebraska have caused more than $1.5 billion in damage. And in South Dakota alone, tens of thousands of Oglala Lakota people on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation are fighting severe flooding that has resulted in a humanitarian disaster.

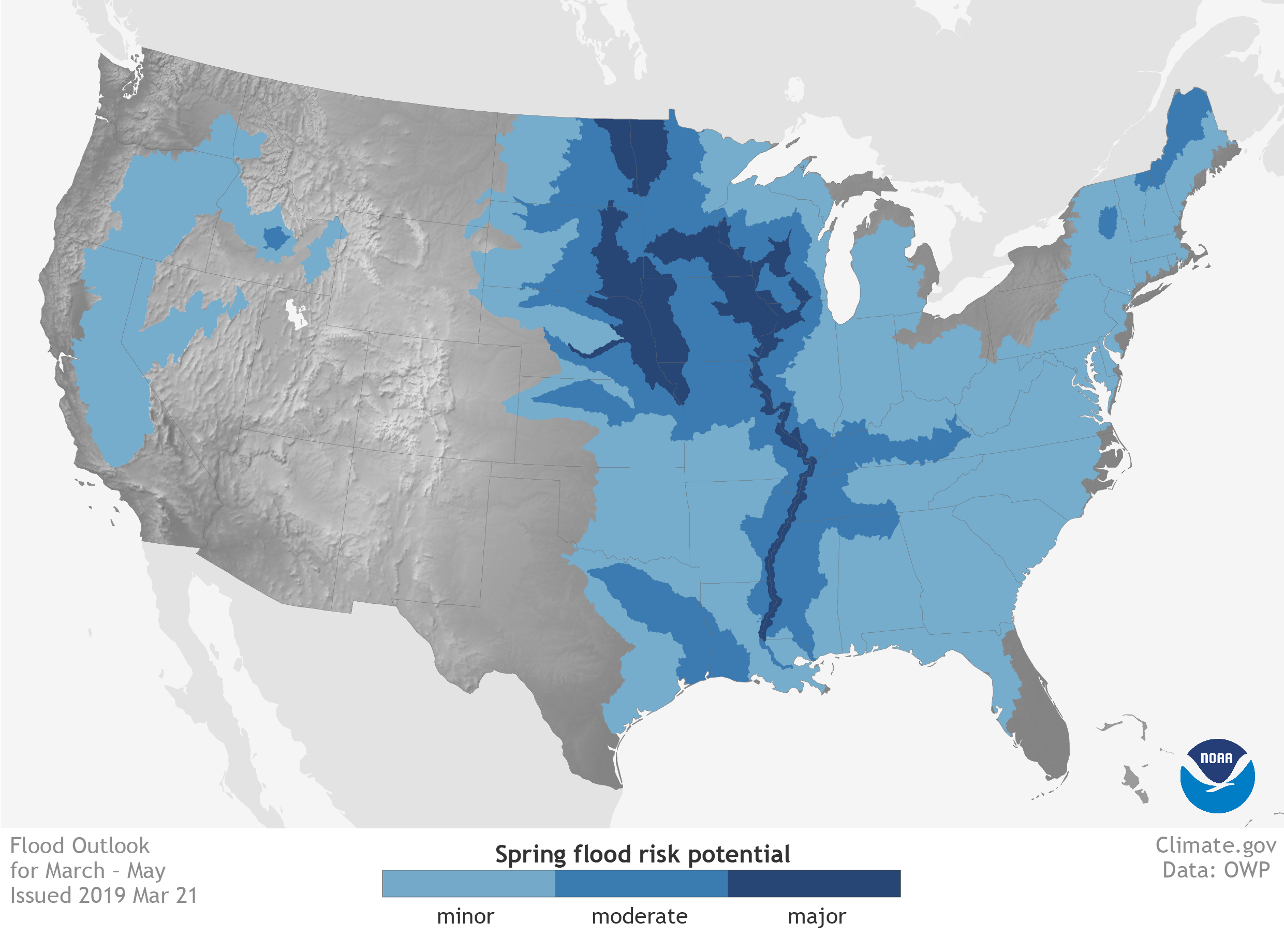

The situation in the US will not improve anytime soon. NOAA's Spring Outlook predicts flooding in the US could continue for months. Forecasts are for more than a little bit of water: From now until May, parts of 14 states are at a greater than 50 percent risk of major flooding, which NOAA defines as waters that require evacuations and "extensive inundation" of buildings and roads. (Just last year, NOAA's map had no regions with major flooding predictions. In 2017, only a tiny part of North Dakota was predicted to have major flooding.) Altogether, there are 200 million Americans at risk of flooding this spring.

As climate change increases the severity of major storms and floods, people will need to prepare, prevent as much destruction as possible, and assist others in need. Often, disaster relief efforts will need to extend much longer than the storms themselves. Take, for example, what's happening now on the Pine Ridge Reservation: although the tribal emergency management office is coordinating immediate efforts, community organizations will be dealing with the aftermath of the flooding for months — or even longer. People outside the reservation may want to contribute to the long recovery, or to send aid to Idai victims. But what are the best ways to do that?

Check on friends and family in the flooded area

Floods are incredibly complex. Though it may seem obvious when to worry, there are actually many factors that determine when and where a flood will occur, including environmental characteristics like drought, soil moisture, and streamflow. In a flood situation, pay close attention to local emergency management announcements, especially recommendations to evacuate.

The same goes for checking in with loved ones in harm's way. Kellyn LaCour-Conant, a Coastal Resources Scientist with the Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority in southern Louisiana, and her extended family have lived through Hurricanes Harvey, Maria, Katrina, and several other major storms. Before forecasted weather events, LaCour-Conant's family checks in with each other to make sure all family members have the information and essential supplies they need. They've been in enough storm situations that they "know whose homes are more likely to flood or on higher land so [they] can evacuate if need be." You can check FEMA flood maps by address and read more about hydrological risk for specific locations ahead of storms.

After the storm passes, volunteer to help deliver supplies or clean up — like community members have done in Pine Ridge. "We're a communal society, we view each other as relatives. We're seeing a lot of people taking care of their neighbors," says Ernest Weston, Jr., the director of operations for Pine Ridge Reservation Emergency Relief, a community organization that's working to provide post-disaster relief. Even if you're not physically close, get in touch with people to ask what they need.

On the Pine Ridge reservation, Lester Rowland loads containers of drinkable water into his car.

Lt. Col. Anthony Deiss

Pay attention to media coverage and amplify requests for help

Look to local government social media channels or find local organizations who are disseminating reliable information. They may provide links and guides on where to funnel resources. Be aware of how both media outlets and personal friends are talking about disasters. Communities of color are often labeled resilient. But as Tatewin Means, executive director of Thunder Valley Community Development Corporation (a grassroots non-profit near Pine Ridge) says, "Yes, we can withstand anything that's thrown at us. That doesn't mean it's right."

Donate money before tangible goods. Then, focus donations on requested items

Everyone I talked to agreed that if you are financially able to donate, money is the most helpful contribution. LaCour-Contant says, "Some people prefer to donate tangible goods, because it feels more personal or they like the reassurance of knowing exactly how they’re helping. That’s fine, but please don’t donate things that cause more chaos and headaches."

In Pine Ridge, Means highlighted the need for philanthropic investments in the community, both for flood recovery and to improve conditions on the reservation in the future. For now, Weston specifically requested five gallon buckets, rain and muck boots, shovels, cleaning supplies, and non-perishable food. This kind of help is "greatly appreciated." (Click here to donate to Pine Ridge Relief or find out more about how you can help.)

Flooding in Fremont County, Iowa.

Fremont County, Iowa Emergency Management

Donate as close to the people in need as possible

Try to donate to community organizations with pre-established connections in the area of need. LaCour-Conant says, "Donating through big, national organizations means there will likely be delays in when that donation actually gets in the hands of someone displaced by climate disasters. Donate to local organizations first—they’re the ones who are on the front lines, know the community, and can mobilize before some big organizations." It can take some research effort to figure out where to donate, but it's worth the trouble to make sure your money is making the largest impact.

Stay engaged after the immediate disaster is "over"

It's especially important to donate or volunteer even after the news cycle moves on. Massive writer Anna Robuck, whose family in North Carolina was affected by Hurricane Florence, says, "The rebuilding stage is the toughest part. Individuals, community organizations, first-responders, animal shelters, and pretty much everyone in an impacted community will be reeling in some way, and will need huge reserves of energy or resources to get back to normal!" Be aware that some disaster victims also continue to experience mental health struggles, including post-traumatic stress disorder long after the waters recede.

Don't ask, "Why don't you just move?"

Although it may seem risky to live near rivers or coasts, there are many reasons why people people might choose not to move away, such as finances or a deep connection to the place. "This is where I grew up, where my ancestors lived and are buried, where my family is, where my culture thrives, and where I feel safest. I will gladly live and die on the Gulf Coast working to help my community survive." says LaCour-Conant. Remember that natural disasters (and their long-term effects) are often exacerbated by colonialism, unequal distribution of resources, and anthropogenic climate change; the victims of these forces shouldn't be forced to move away.

Advocate for better environmental policy and more funding for green building projects

No matter where you are, you can encourage lawmakers to keep climate in mind during all policymaking decisions. Prevention is the key to mitigating the impacts of climate change, but resilient building projects aren't always prioritized. "Keep resilient shoreline development and water quality issues on the ballot and regulatory agenda long before a flood, and well after flood waters recede. If these items are not properly addressed before a catastrophic flood, the clean up is that much worse," Robuck says. Means points out that "being environmentally responsible is expensive in this day and age." Though Thunder Valley wants to build new construction that meets lofty sustainability goals, they need the funding to do so. "Green building is reserved for those in the upper echelons of society, and it shouldn't be that way."

When new climate disasters happen every day, it's easy to think that there's nothing we can do to help. But instead of feeling hopeless, consider taking some of these steps to help communities prepare for—and bounce back—from disaster.