Gabriela Serrato Marks

It's time to stop excluding people with disabilities from science

You can be a great scientist without being able to carry a 50-pound backpack out of a cave

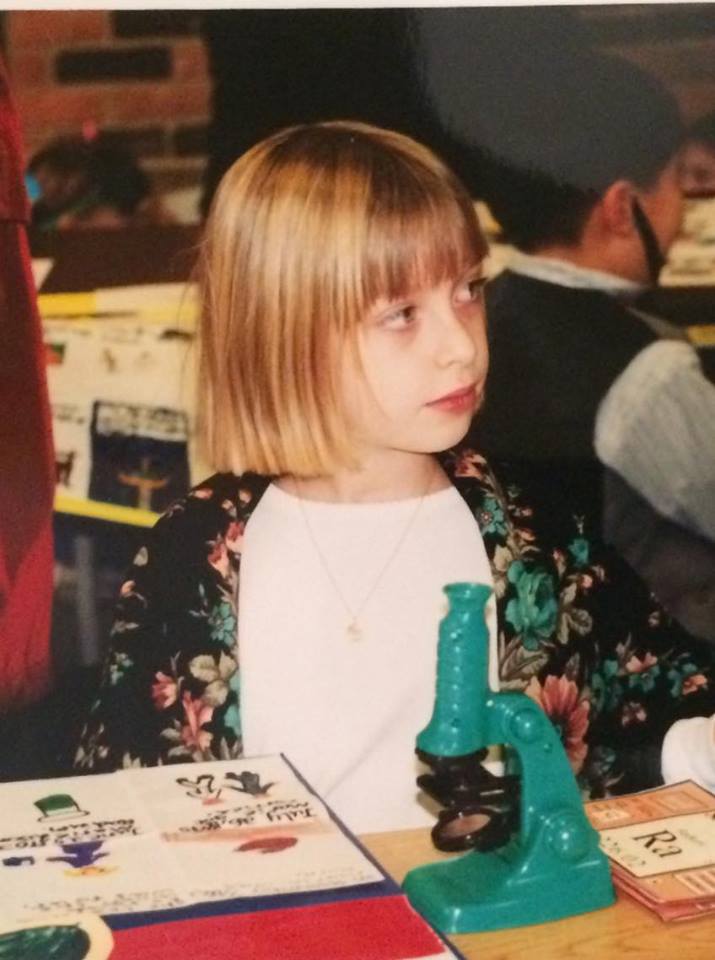

As a kid, I loved to spend all day playing in dirt, digging holes at the beach, and adding pebbles to my rock collection. I turned that curiosity into a career in geoscience; now, I'm a full-time nerd, working on a PhD in marine geology. My field work involves hiking into caves, finding large stalagmites, and carrying them back out. Back in the lab, I saw them open and drill out powders to analyze their chemical ratios. I have really taken my childhood rock collection to the next level.

But almost two years ago, during the first year of my PhD, I started having pain in my muscles and joints that went from annoying to life-altering in the span of a few months. My body has seriously bad timing – graduate school is hard enough on its own, but now even walking up stairs or cutting vegetables is painful and exhausting. Frustratingly, I still don't have a diagnosis. Now I am a cave scientist and geochemist with a chronic pain condition, which means that I have to choose between putting myself into painful fieldwork situations or missing out on those experiences completely.

There is a third option, which sounds the best (in theory, at least): I can change how I work so that I can still participate fully in research and learning opportunities. But this is a challenge that is bigger than just me: it involves a field-wide rethink of how we work to accommodate people who need different conditions than what's standard to thrive. Teachers, university administrators, and professional societies need to consider ways to make natural science more accessible and welcoming for people with physical disabilities – not just because we need everyone's talent, but because it is the right thing to do.

The young geochemist

Gabriela Serrato Marks

There are 75 percent fewer people with disabilities working in STEM fields than in the general population. There are lots of potential reasons for the deficit, many of which vary based on the type of disability being discussed. But one challenge I am familiar with is specific to natural sciences: access to outdoor spaces. Although there have been some efforts to make public spaces more physically accessible, by adding ramps or automatic doors, the results tend to be disappointing. As an example, there is a state park in Massachusetts (where I am from) with more than 400 acres of land … and the only wheelchair-accessible path is a 0.25 mile-long strip near the parking lot. Young children with mobility limitations can't dig holes if they can't even get to the beach.

In addition to those early experiences, so pivotal to my own path, institutional policies and a lack of accommodations can keep talented people out of geoscience, or make the path harder than it should be. A recent study found that almost 90 percent of survey respondents thought that field experience should be a requirement for undergraduate geology majors. My goal is to be a professor of geoscience, but there is no guarantee that I will be able to lead field trips with steep hikes into caves or even spend an hour on my feet to teach a lecture.

On the other hand, there is a lot I will be able to teach my future students. This year, I learned to code in Python and do high-resolution image analysis, which allows me to participate in cutting-edge research. I agree that you can learn a lot from lying on a rock with a magnifying glass, looking at the texture and types of minerals, but there are a lot of other skills that are just as important. Struggling with my pain condition has helped me realize that there are so many ways to be a good natural scientist, and many of them don't involve carrying a 50-pound backpack out of a cave. I don't need to be a field geologist to succeed, but I do need my future colleagues to understand that my contributions are just as valid as theirs.

Challenges and stereotypes shouldn't keep me (and others like me) from realizing my goals. As the effects of climate change become more pressing, we need all hands on deck to find solutions and understand complex climate processes better. The next decade will be full of job opportunities in geosciences – almost half of current geoscientists are approaching retirement.

Because of the range of different needs that people with disabilities have, from American Sign Language interpretation to extended time on exams, full access might seem like an insurmountable challenge. But what about the huge range of different skills and ideas that we bring? It certainly seems like a worthy investment to me.

It's also totally possible to do: take the International Association for Geoscience Diversity (IAGD). The organization leads field trips where participants work in small teams, with scouts who can bring back rock samples if it is too challenging to reach the site, sign language interpreters to provide full access to lectures, and textured maps for people with low vision.

Gabriela Serrato Marks

Institutional policy changes don't have to be huge to be impactful for people with disabilities, and they often end up helping everyone. For example, faculty at Bowdoin College just voted to switch to 10 minutes between classes (instead of five) to give all students more time to get across campus and reduce late arrival to class. This small change is particularly welcome for students with limited mobility like Daisy Wislar, the president of the DisAbled Students Association at Bowdoin (and a friend of mine). She and other members of the group have been pushing for the time increase for two years.

Teachers and hikers alike can learn from these efforts to decrease barriers for people with physical disabilities. Next time you are at a park, ask yourself, "How would someone using crutches access this space?" If you are designing a field trip, build in extra time and touch base with all your students about their accessibility needs, even if you don't think anyone needs it.

Gabriela Serrato Marks

Most importantly, involve people with disabilities in initiatives and programs from the very beginning; in other words, ask us what we need, compensate us for our hard work, and recognize our contributions. These principles apply to other diversity initiatives, too, which are equally important (geoscience has the lowest racial and ethnic diversity of all STEM fields).

I am convinced that it is possible to make natural science open to all dirt-curious kids with policy changes and decreased stigma. I want to be known for my teaching and paleoclimate research, but I need a chance to make those impacts.