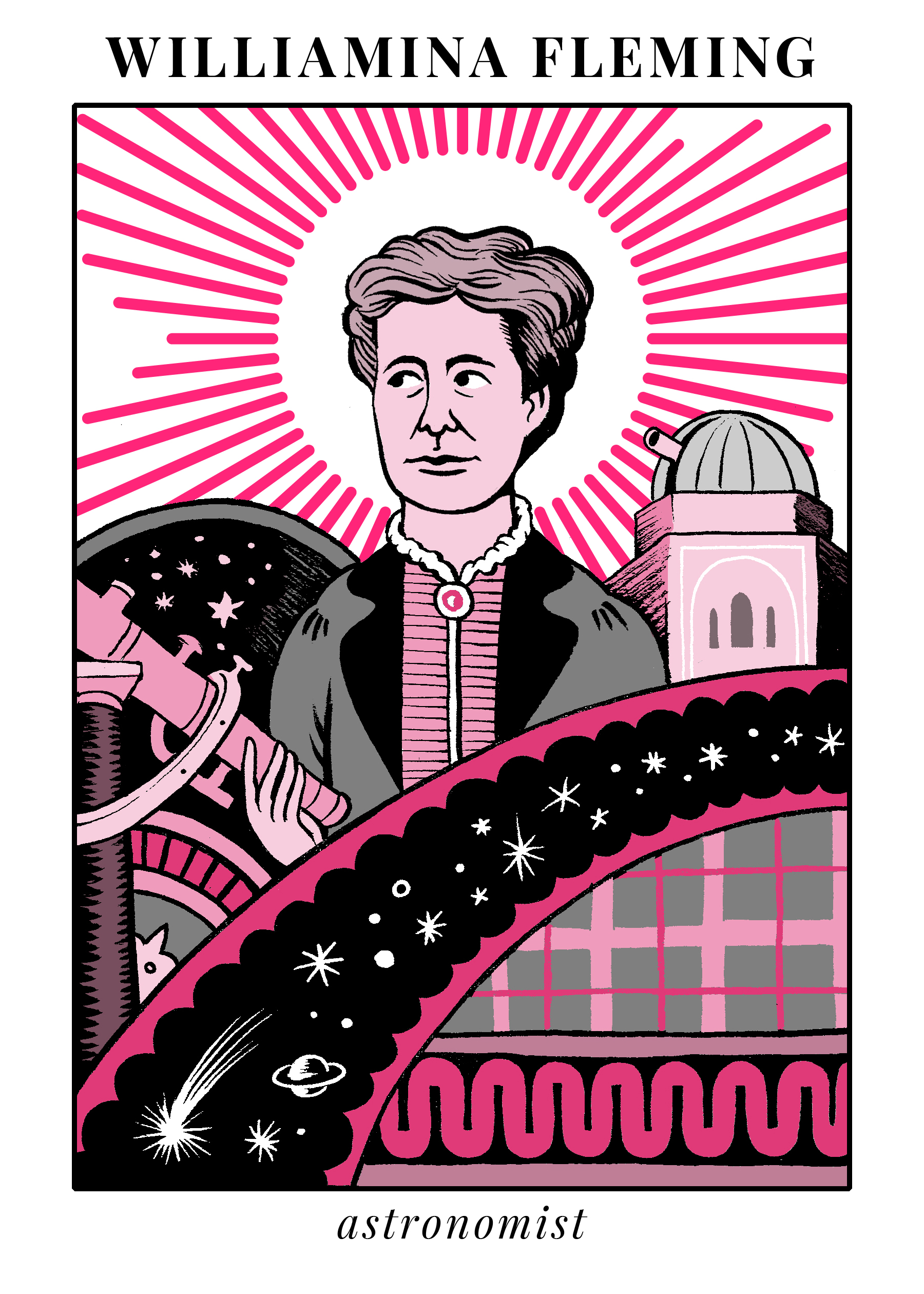

Meet the astronomer who changed how we see the stars

Williamina Fleming pioneered a system for classifying stars and discovered the Horsehead Nebula

In 1879 Williamina Fleming began working as a maid for Edward Pickering, the director of the Harvard College Observatory. Just 23 years old, Fleming was well acquainted with hard work. By 14 she was helping to support her family as a student teacher and, at 21, she had packed up and moved with her husband and small son from Scotland to Boston, Massachusetts. So, when she found herself abandoned by her husband in America and tasked with working as a housekeeper to provide for her son, she rose to the challenge.

Pickering saw a potential in Fleming that went far beyond her domestic duties. So, soon after hiring her, he offered her a part-time position at the observatory. He didn’t know it then, but that decision would prove pivotal for the burgeoning field of astronomy.

Illustration by Matteo Farinella

Fleming quickly ascended to leading the observatory’s team of “computers”—women who analyzed photos of space. Her work required using a spectrograph, which separates the light coming from the stars into its component wavelengths, much like a prism, and displays them as distinct lines on a single image.

Among the entropy and disarray, Fleming saw an opportunity for order and organization, and developed a system of classification based on the stars’ spectra. Using this system, dubbed the "Pickering-Fleming System,” she categorized more than 10,000 stars, published in the inaugural edition of the Draper Catalogue of Stellar Spectra in 1890.

The advancements Fleming made in astronomy—discovering 10 new novae, 59 nebulae and over 300 stars—outpaced her peers. Among the most noteworthy of her discoveries are white dwarf stars and the Horsehead Nebula; in 1898, she was honored by a national gathering of astronomers for her contributions to the field.

The Horsehead nebula, which was discovered by Flemming.

Over the next decade, Fleming continued to receive recognition for her work. She was named Curator of Astronomical Photographs at Harvard, elected as the first American woman to be an honorary member of the Royal Astronomical Society of London, and served as an honorary fellow in Astronomy at Wellesley College. She received the prestigious Guadalupe Almendaro medal for her discoveries.

Fleming died in May of 1911, but throughout her lifetime, she excelled and was credited in a field in which women were rarely given their due. Nonetheless, she understood the plights females faced in the profession. Recognizing a need for change, she championed the effort to achieve equality for women in astronomy, speaking out against the status quo of unequal pay between men and women in the 1893 treatise, “A Field for Woman’s Work in Astronomy,” in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics.

“We cannot maintain that in everything woman is man’s equal,” she said at the Congress of Astronomy and Astro-Physics in 1893. “Yet in many things her patience, perseverance, and method make her his superior.”